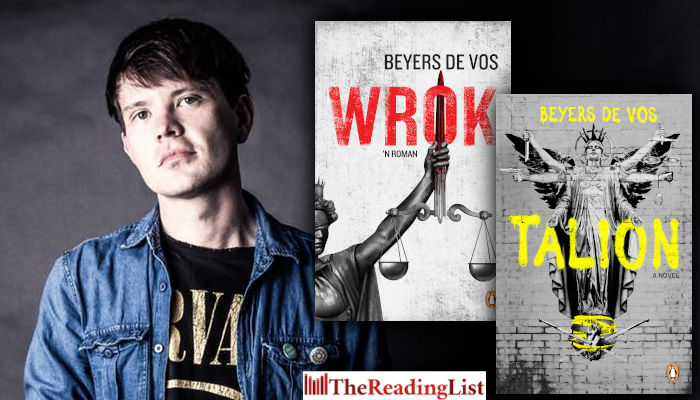

One city. Five people. A bloody trail of revenge. Read an excerpt from Beyers de Vos’s debut novel Talion

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from Talion, Beyers de Vos’s gripping literary debut.

Talion captures the dark and messy consequences of grief, anger and revenge.

De Vos is a writer, editor and journalist who lives and works in Cape Town. He was prose editor for the literary journal New Contrast, and holds a master’s degree in creative writing from the University of Cape Town.

‘Freya Rust wouldn’t have had the courage or audacity to kill a man. But she isn’t Freya Rust anymore. She is someone else, no one else. Stories change. Once upon a time there was a young woman named Freya, whose brother was killed by a demon. She became a fierce warrior and avenged him. She slayed the demon. And as a reward, they made her a god.’

About the book

Pretoria: Five people with distinct lives, living in different sections of the city, but all tied together in ways they have yet to understand. Ben and Freya are orphaned twins, and Freya believes them to be as close as twins can be, but Ben has kept secrets from Freya that have led to his murder. Mr October is a widowed father, a rugby coach at a high school, and a devout Christian, but harbours a dark past that haunts him. Slick is a selfharming drug dealer, who, shaped by the brutal lessons of his mentor, Mama Africa, knows retribution is a vital aspect of staying in control. And Nolwazi is an inspector with the Brooklyn Police Department, who wants to do her job properly, but is thwarted by an over-worked system and corrupt peers.

Why did Ben die? Who killed him? Who will be the one to achieve justice? And is justice even a possibility?

A gripping literary debut, Talion captures the dark and messy consequences of grief, anger and revenge.

Ook in Afrikaans beskikbaar as Wrok.

~~~

Read an excerpt from Talion:

1.

The building that stood here was ripped out by its roots from the concrete skin of the city, leaving only a scar. And one other thing: a wall, grey and untarnished, a sole survivor of the carnage.

Painted onto the wall, spreading giant black wings, an angel stands in darkness.

The angel wears a black gown and her black hair is blowing in an imaginary wind. She is blindfolded. In her left hand, she holds the scales of justice. She is strained, constrained. Underneath the angel, at her feet, a crowd of small people has gathered. They are prostrating themselves in front of her, faces eager, full of adoration. But along the edges of the crowd, skirmishes have broken out; people are stabbing one another to death with tiny, badly drawn knives. Some are tying nooses. Others are flinging themselves off the edge of the world. Still others have begun to climb the angel, using the folds of her gown to pull their way up; a few are urinating on the people below.

At least one of these tiny people has reached the summit of the angel, standing on her left shoulder. This man has reached up towards the edge of her blindfold and lifted the heavy fabric. From underneath, an eye is leering at the street. A fierce, red eye.

In the angel’s other hand, the right one, she holds an erect penis, as if she were using this as her sword. The penis is engorged and ejaculating, and from the angel’s hand great white globs are falling, killing the people at her feet who are caught in the mighty splashes. Drowning in her fertile fury.

When the wind blows through Pretoria, it is possible to imagine the angel’s wings flapping furiously, her chest heaving. It is possible to imagine her breaking free, a great avenger, seeking out those who have done wrong. It is possible to imagine her white, sharp hands and her stark, bold mouth stunning the beholder with their power, their ferocity.

Beneath the angel, in angular black letters, it reads: I am coming for you.

And from her angry eye, the city watches. And it sees.

Friday

2.

Ben hears the gunshot before he feels it.

The car is still running, the rumble of the engine unnaturally loud. His foot is slipping off the clutch. His blood is spilling out behind him, wetting the seat. His whole body is trying to panic, trying to cry out, trying to flee. But he can’t move; his lungs are filling with blood.

The car coughs. Dies.

People are shouting.

He saw the shooter. He saw the man raise the gun – satisfaction like oil all over his face, black and molten – and squeeze the trigger. He knows who’s shot him. He knows why.

The bullet came through his window. Why had his window been open? ‘Ben! Jesus Christ!’ She is at the window suddenly, wildly. Fear blooms in her eyes, bright and blue. He wants to tell her that it’s all going to be okay. It’s no big deal. Like the time they were playing Touchers and he fell through the glass table. Does she remember? There was blood all over the white living-room carpet, the carpet their mother loved so much; he’d got fifty stitches. This is just like that. This is just another scar.

But a black fog is rolling through his eyes. His heart is losing rhythm, is a song falling from its crescendo. He cannot move his tongue; he does not have any last words.

He is so tired.

His mind slows down. Every sensation is travelling from very far away, reaching him through a cloudy tunnel. Colours are fading, blending into each other, losing intensity.

There are more people around the car now, shouting and running. She is opening the door, undoing his seat belt. ‘Don’t move him!’ someone yells.

She takes her jersey, takes his hand (grasps it), and pushes it down over his wound. ‘Ben! Can you hear me? Don’t close your eyes, okay? The police are coming. Don’t die. Jesus Christ, don’t die!’

He won’t die, he won’t. He’s just going to close his eyes. Just for a second.

3.

Sergeant Nolwazi Mngadi is having a bad night.

On duty for little over two hours, she’s already fed up. She tosses a chocolate wrapper out the car window, rubbing her bruised nose. She’s sulking, because a shoplifter had managed to cuff her across the face while thrashing around, shouting about police brutality. Later (Nolwazi still trying to stem her nosebleed), the little criminal’s father berated Nolwazi for almost an hour: why wasn’t she doing real police work? Why wasn’t she chasing real criminals? Why wasn’t she out catching rapists? Never mind that his daughter had been caught red-handed.

After that, she was called out to deal with a gang of streakers. When she arrived (five minutes before anyone else did), the streakers scattered, and she was forced to chase a skinny petulant man through the streets: a naked man who turned to look at her – leering, hands on his genitals – before jumping a fence and evading arrest. She gave up the chase after that. Nolwazi would be the first to tell you – she isn’t built for running.

She should never have asked to be transferred to the Brooklyn station.

Brooklyn, she had thought. Sophisticated area, low crime rates. Nothing more than petty theft and drunken driving. Maybe the occasional hijacking. But no more bodies hacked to pieces, no more murder, no more gangs, no more child abuse, no more rape. No more babies in garbage bins. No more happy-just-to-be-alive at the end of the day. Brooklyn had a kind of heroic ring to it. Brooklyn PD – like in New York. Like in the tv shows she liked.

But no one had told her that Brooklyn Police Station wasn’t technically in Brooklyn at all, but in Hatfield: the station was only a block away from the university campus.

Students. Students everywhere. Drunk, stupid students who spend their nights getting wasted and pissing her off. At least in Mamelodi she was treated with respect. The badge meant something. But here? Here it’s a scowl and a bad cup of coffee. Here she spends her days dealing with privileged, part-time racists who think they’re above the law.

When she arrives, Frik and Hans have their arms crossed, staring down

at a young man standing in the half-light of a street lamp. Not a man, really; a boy no older than twenty. He has a cigarette hanging limply from his lips; he is shuffling from foot to foot. They’ve pulled him over on a quiet residential backstreet. Above the treeline, the glow of Hatfield’s bars is visible, and to her right – on the dark horizon – the loops of the highways that feed it. But she could almost pretend none of that exists between these normal houses, between these tranquil streets just outside the reach of the pestilence of Hatfield. Nolwazi often parks her car in one of these streets, moving away from the neon-loud bars, the clouds of music. She can switch off her radio and escape into another world – a world where justice isn’t a broken, ridiculed victim; a world where heroes exist.

‘Hey,’ she hears Frik say to the male suspect as she gets out of her car, ‘do girls actually like those?’ He is pointing to the black, too-tight skinny jeans the guy is wearing. The young man stutters, but Frik bares his many teeth and laughs, not looking for a response.

‘Evening, Nolly,’ he says and nods.

‘Evening, Frik. Hans.’ Hans ignores her, as usual. Because she’s black, because she’s a woman, because she outranks him – or some combination of the three. It doesn’t particularly bother her. She’s used to it. At least that’s what she tells herself.

‘We caught them buying weed from Bra Joe outside there by The Dank Den. They say they were just asking for directions. But I saw Bra Joe give them the stuff with my own eyes. Searched the car twice, and the guy, but the chick was the one leaning out the car, doing all the talking. We think she’s got it somewhere.’

The female suspect is standing slightly apart from her friend, smoking a cigarette and looking at the police expectantly, daringly, like she’s sharing a secret with them. She is dressed in a short white dress, tight over bright blue tights. She’s taken off her shoes. Her painted toenails glimmer every time the police lights flicker across them: blue and red, blue and red.

‘Come over here, please,’ Nolwazi tells the girl. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Sophie,’ the girl says, putting out her cigarette on the kerb, leaving the butt lying on the tar.

‘Do you have any marijuana on your person, Sophie?’

‘Not tonight, ma’am.’

‘Stand over here with your hands on the car and spread your legs.’

Sophie calmly does as she is told. There is a small smile on her lips. Her friend is watching anxiously.

Nolwazi hates body searches. She stands behind the girl and quickly manoeuvres her hands up her legs to just before the panty line. ‘Stand up straight, please, arms out.’ She checks from below the panty line, up the girl’s back. She checks down both her sides. ‘Turn around.’

Sophie is taller than she is.

‘Are you sure you haven’t smoked any marijuana tonight?’

‘No, ma’am.’

‘I can smell it on your breath.’ Nolwazi is lying.

‘Must be the cigarettes, ma’am.’

She runs her hands up Sophie’s stomach and under her breasts (almost lifting them out of the dress). Clean. She doesn’t like this girl, tall and sexy and relaxed. She could ask her to undress, squat, lose a little of her dignity, but that would require taking both suspects back to the station. Booking them. And Nolwazi can’t see where Sophie’s possibly hidden the marijuana, unless it’s inside her vagina. ‘She’s clean, guys.’

Hans, who has been watching her exam ardently, his big red lips slightly open in anticipation, slams his hands into the side of the vehicle. ‘Fuck’s sake,’ he says.

Frik merely runs his hands through non-existent hair and asks, ‘You sure, Nolly?’

‘Yes. Sure.’

Sophie and her friend look relieved.

‘Okay, you okes can go. But don’t let us catch you buying weed again,’ Hans says to them. Nolwazi can practically see the waves of disappointment peeling off him, his face crumbling in on itself. Frik and Hans spend their nights camped outside wherever Bra Joe is operating – it’s easy, it’s neat, and usually no one notices if only some of the evidence makes it back to the station. Unless you’re Nolwazi, in which case it’s the first thing you notice.

‘We won’t,’ Sophie says, mirth in her voice. She and her friend scramble back into their car. Nolwazi can hear their shouts of relief echo down the street – at least someone’s going to have a good night.

A harsh, electronic voice interrupts: ‘Shooting on Burnett Street,’ it says, ‘white male shot in a blue Citi Golf. All available officers please respond.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Beyers de Vos Book excerpts Book extracts New books New releases Penguin Random House SA Talion