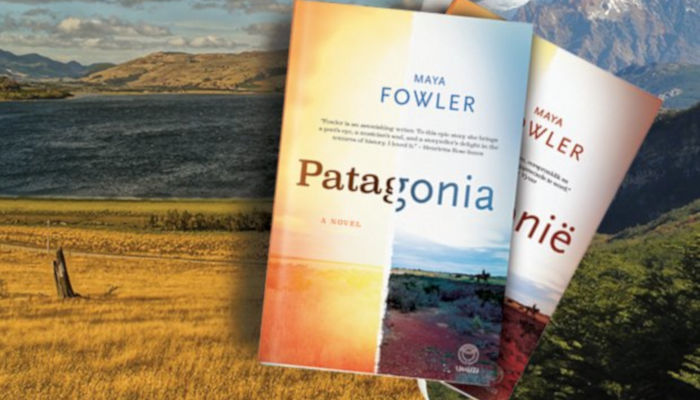

‘The first thing Basjan did on arrival in the new land was to spit on it’ – Read an excerpt from Patagonia by Maya Fowler

More about the book!

Read an extract from Patagonia, the latest novel by Maya Fowler!

About the book

Tertius de Klerk: Afrikaner, hapless academic and potential dinosaur under pressure from all sides dreams of escape. When a drunken one-night stand with a student turns into a Facebook embarrassment and an altercation, Tertius is convinced the time for escape has come. Like his great-grandfather Basjan before him, he flees South Africa for Argentina. It is an act of desperation, but also of adventure: this is his opportunity to look up his long-lost relations on the windswept plains of Patagonia where he might, finally, connect with the earth and make a man of himself.

Click on the link for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from Patagonia:

The first thing Basjan did on arrival in the new land was to spit on it. It chagrined him that that was the first this land of grey dust got out of him, but it was necessary to rid himself of the taste of vomit. The salt water had been no help.

The wind that had blasted the ship so still raged. Now, along with the chewing tobacco he stuffed into his cheek, Basjan received a mouthful of grit. He did not dare open his eyes too wide, but looked out over the sea; the water was darker than at the Cape. And saltier, it seemed.

The soil beneath his feet was as brown as a warthog, utterly different from the sand along the Cape coast – golden-white those beaches were! These reminded him of sandy river beds rather than something that embraced the sea.

All around, families scurried. The women held onto their bonnets as they went. One nearly bumped into a mule when the wind whipped at the fabric and obscured her view. Someone had sent horse carts, and the Boers set to the job of packing them. Infants, wooden chests, bundles of wood, even a pump organ. There went the wide head- and footboards of a stinkwood bed, someone’s inheritance, probably. One of the legs was charred.

He stared at the men who seemed, after the long voyage, unable to find their footing on land. Look at those bandy legs! As off-kilter as Humpty Dumpty himself, they danced a merry jig trying to stay upright, Dominee Deetlefs included. Ah yes, perhaps tonight they would enjoy the jollity of real dancing. The Koffiefontein boys had brought along the concertina and mouth organ, after all, and he had his violin.

The wind kept boxing him about the ears. At times it out-thundered other sounds, while other times it carried them – as now, the lowing of a cow. A young man was trying to lead her ashore, but her neck strained and eyes rolled. Closer by, a horse was blowing hard, and from above came the screeching of a gull. The horse beat its hooves.

Basjan lent a hand with the cartage, then helped a string of infants onto their mothers’ laps before taking a seat on a wagon himself. He found himself beside scrawny young Bertie Cilliers with his wild green eyes and a sparse yet unkempt beard. During the voyage he had seen the young man in the distance only. Now he had best start the conversation – the best way to nip the usual questions and nonsense in the bud.

“So tell me, Neef, would it be sheep or cattle for you here?” Everyone said the cattle farming was farther north – he hadn’t managed to catch the name, somewhere like Palmitas. Down here, Patagonia, was sheep country. But it was a way to steer the conversation into the future, instead of the constant bellyaching over the past and who had done what wrong.

What was done, was done.

The man scritch-scritch-scratched at his neck in the manner of a flea-ridden dog. He sucked in his lips like a weak cub at the teat, or an old toothless crone. His eyes twitched. Basjan exhaled slowly through his nostrils. He picked up the fellow’s hat where it had landed behind him on the wagon and dusted it against his knee. The young man did nothing to retrieve it; Basjan slapped it back onto the chap’s head.

“You’ll have to tie that thing to yourself,” he said and tore them each a portion of chewing tobacco.

The man nodded. He’d heard, at least, but he looked into the distance and clung to the brim rather than securing the hat in any fashion. Basjan offered the tobacco a second time, and when the fellow noticed he simply shook his head. It didn’t seem he’d respond to the question of cattle or sheep, but by the state of him, Basjan judged he probably couldn’t tell the difference between the two anyway. His eyes stayed on the horizon, or beyond, and his face was red with sunburn. The lips were peeling, and the forehead, but underneath the skin was smooth as glass. Basjan took another look. Initially the beard had made him assume the man was older; only now did he realise who and what the poor sod was. Boys under sixteen had routinely been rounded up with the mothers and taken to the camps, unless they managed to run off to commando. Many had not survived. Some had.

Basjan pushed his hat down on his head, turned away from the boy and said no more.

The undulations in the parched earth surprised him. He had expected flat terrain, like the Free State. The scrub looked like the southern Free State at its driest, exactly so, but the mountains were Karoo – a landscape until recently known to him only from paintings. On the train journey to the Cape, though, the Karoo had lain before him open-armed, wide as the heavens above, such that he briefly entertained the thought of jumping off the train there and then to start his new life as Jans Pelser.

But had he done that, he would still have had the Khakis lording it over him; and besides, that Salome might still ferret him out. She had relatives around Philippolis, a touch too close to the Karoo.

Ah, no, Patagonia was a far better move; secure. Though the wind could blow you out of your breeches, and the soil looked somewhat paltry, it was a rugged and enduring corner of the world. Stark and robust, just like the very Boer himself. Just look, here in Comodoro a bare block of mountain rose straight from the sea. Dark grey it was, with ridges raked into its sheer face.

The wagon turned a curve and a tent village appeared. Hang, but it was a spirited bunch of horses: Basjan had to put out his hands to keep himself from keeling over. He came upright to see the young man’s face contorting. His eyes were wide and he gasped like a catfish on dry land. The tents were cone-shaped and made of white canvas. The fluttering of wind on cloth became audible. Then came some mumbling: the young man looking up at the clouds, seemingly at prayer.

Ja, kyk, in this place people would be wearing out their knees in no time, that was for jolly sure. From the start, he had wondered about the fertile land they had been promised, the grazing that was supposedly so lush, but he hadn’t asked any questions.

It wasn’t lush grazing he had come for.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Maya Fowler Patagonia Penguin Random House SA