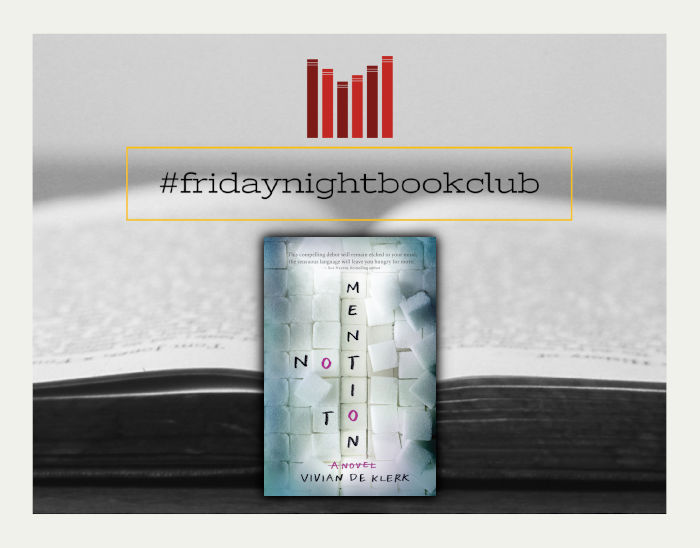

Friday Night Book Club: Read an excerpt from Vivian de Klerk’s must-read debut novel Not to Mention

More about the book!

The Friday Night Book Club: Exclusive excerpts from Pan Macmillan every weekend.

Get comfortable this evening with a glass of wine and an excerpt from Not to Mention, the must-read debut novel by Vivian de Klerk.

Not to Mention is part diary, part memoir, part love-hate letter to the mother who fuelled her daughter’s addiction as steadily as the world ostracised her. The destructive power of shame and society’s harsh judgement of people who are ‘different’ is matched by the immense courage of a young woman who is determined to be heard.

About the book

As her 21st birthday approaches, Katy Ferreira has not left her bedroom for close on two years. In fact, she has not left her bed – at 360 kilograms, she simply can’t.

Characterised by an indomitable spirit, Katy tries to make the best of a bad situation. She does the crossword in the Herald newspaper her mother brings home, consumes the food she craves – biscuits, pies, doughnuts, litres of fizzy drinks – and waits in hope for insulin and a solution to her plight.

To pass the time she begins to compile her own crossword in one of the Croxley notebooks that have been unused since she dropped out of school. Within each cryptic clue is a message, an attempt to explain how it feels to be ‘the fat girl’, how taking comfort in sweet things as a grieving and lonely child escalated into a deadly relationship with food and a psychological and physical disease.

The process triggers splintered memories of dark family secrets and hints of culpability. As Katy finds her voice – quirky, macabre, devastatingly astute and viciously funny at times – the notebooks fill up.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

4 October 1980

So now I’m going to start with your first clue:

3 down: A curious attire for a brief solo (7 letters)

The answer to this one is ‘arietta’. It’s an anagram of ‘a’ and ‘attire’ – the word ‘curious’ acts as an instruction to mix the letters up. An arietta is a brief solo, and I like to think of this first big crossword as my brief solo: a chance to speak up and maybe be heard. It’s never over till the fat lady sings, and that’s where the Croxley books are going to come into the picture. The fat lady was Brünnhilde in the Valkyrie, according to Brewer’s, and I love to picture her, looking rather buxom with her helmet and spear, singing ‘Götterdämmerung’ for twenty minutes at the end of Wagner’s opera. Well this is my song. It’s a nice clue to start with because, let’s face it, my attire, or lack of it, is rather curious, to say the least. How did that go, mother? Did you get it without reading the answer? And did the explanation help? Don’t give up too soon if you found that one difficult – things get easier when there are a few letters written into the grid. This clue naturally brings me to my attire: I’m completely naked here under the sewn-together sheet you cover me with every day for the sake of modesty. It’s easier that way, I know – no dressing or undressing required, making the cleaning quicker – I get it, but somehow it doesn’t feel right. A virtual prisoner for the last two years, reading and doing puzzles to keep myself busy, trying not to worry too much about this wretched diabetes. Trying to keep hopeful. The Herald today is full of reports of unrest, with disruption and boycotting at 33 black schools. Pupils are being accused of intimidation under the Riotous Assemblies Act, and some are being held in detention without trial. But my detention is at home – and it’s been such a long time now, the days flicking by, hard to pinpoint, weeks, months and even years gone in an empty moment. The endless expanse between morning and evening is yawningly deep and breathtakingly boring. Here in bed, under the two sheets you sewed together, my layers of blubber keeping me warm, protecting me from feeling any hint of chill even on the coldest days, when the wind howls outside and the temperature dips below ten degrees – which fortunately doesn’t happen often here at the coast. Feeling warm: the only positive aspect of getting really fat. I gaze down at my body, which seems so distant, so far away, my head like a peninsula overlooking a vast ocean of flesh, my legs ten times wider and thicker than normal legs, huge tree trunks of bluishwhite marbled meat with occasional meandering veins, like rivers, feeding the fat. My belly overflows and I can hardly see my feet at all, my toes just peeking out beyond the horizon. But in a strange way this corporeal mass is not really me: I only occupy the area above the neck, the bit that has been spared, that still feels familiar and in proportion. The rest of my body has broken loose, and I need your help to rein it in and bring it back to me, so that I can stand up again and walk out of this room one day. The writing might be quite good for me, I think – allow me the freedom to reflect, and to keep my mind off things while we wait for me to get better, and to get a few matters off my chest. My very own arietta – I quite like the idea. I’ve got so much to say about my life. About feeling apologetic and about the eating, of course, all the eating.

10 October 1980

That first bit went quite well, I think. Now I’ll go to the bottom left hand corner and give you the next clue.

58 across: What indulgence! (6 letters)

The answer is ‘pardon’. The word used to seek forgiveness for minor or major offences. The first word – ‘what’ – is often used when you haven’t quite heard what someone has just said, but ‘pardon?’ is a much more polite way of indicating that you didn’t quite get it. And of course one of the meanings of the second word, ‘indulgence’, is ‘pardon’ as well: the Catholic Church used to sell pardons, or indulgences, to sinners – exemptions from punishment, as long as they confessed, and paid up. And of course another way of reading the clue is that the phrase could be an exclamation: ‘What indulgence!’ – to express disgust at piggish or greedy behaviour, in which case the guilty party would ask for forgiveness and say ‘pardon’. A three-way test. (I beg your pardon for eating so much, for becoming so offensive, and for lying here inconveniently for so long.) And I hope you won’t be begging for pardon yourself one of these days. I’ve indulged myself far too much, I know, starting with Mr Patel’s corner shop. I used to walk across the bridge on my way to and from school, until the end of standard six, and every day I’d pop in at that pokey hole-in-the-wall affair conveniently on my route home, near the corner of Main Street just before the turn-off into Masonic Street.

Do you know it? I passed the doorway daily, sniffing at the honeyed scent of confectionery wafting out into the street. Is the shop still there? And Mr Patel? You can’t mistake him: the small, wiry Indian man behind the counter, his yellow-brown complexion gleaming with an oily sheen, his eyes underlined by dark rings so it looked as if he wore make-up. Always there, waiting for customers, keeping guard on the dazzling display behind the glass-fronted counter, which was jam-packed with sweets of every size and shape in all their sugarcoated glory. A jagged crack travelled across the front of the glass, stuck together in a haphazard, temporary way with brown tape, which had curled back on both sides, gooey and black with the grime of years of grubby fingers pointing out something behind the bleary glass. The sweets were neatly organised into little compartments, each labelled and marked with a price: four for a cent, or even eight for a cent for the smaller ones. The heady perfume would curl its tendrils around me from the pavement outside, hinting at Eastern mystery – the smell of a freshly opened lucky packet with its pink candy and a surprise – maybe a plastic soldier, or a swimming goldfish, powdery and sugary, writhing around on the palm of my sweaty hand. I couldn’t ever show you what I got in my lucky packets, because the sweets I bought there were my guilty secret, paid for with the money I took from the jar on your dressing table, where you kept the cumbersome small change you accumulated, but I’m telling you now: I had a sugar binge every day after school, quietly subsidised by your bottomless dressing-table fund. The planning of which sweet I would choose, the execution of each delicious transaction, and the satisfying flavour burst as I walked the last two blocks home fuelled my dangerous habit, fertilised the seed of desire, and took root firmly in some deep neural network of my brain, colonising several million synaptic ganglia in united support of their cause: to send urgent messages of affirmation and satisfaction to the emotional centre of my being. Positive reinforcement, the behavioural psychologists call it. I’d read about it in the encyclopaedia and Stedman’s, but Mrs Davis in the library told me how it worked. I like to think he grew quite fond of me, Mr Patel, as he waited patiently on his side of the cracked glass for me to make my choice, yet he probably never thinks of me now or even realises I’m still in the neighbourhood, lying here in bed. His corner shop was the key to my downfall into the fatally destructive addiction that you fuelled by topping up the fund in your dressing-table jar and slipping me treats after supper. You kept putting the coins there, and I kept on taking them. It reminds me of dad going fishing: baiting the trap, hooking the fish, and slowly pulling it in, but you were a fisherman of a different sort, feeding my weakness and my enormous guilt, growing the dependency that would finally get the better of me. I’m not saying you did it consciously or deliberately, mind you, though some might say so. Maybe if I hadn’t taken that bait, things might have been different, but instead my clothes grew tighter and my body grew podgier, weightier, more portly, stouter and more ponderous, heavier month by month. And slowly I descended deeper and deeper in my downward spiral of negative self-esteem, scorned and unbeautiful. Oh, this is so hard to write about.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Friday Night Book Club Not to Mention Vivian de Klerk