Read an extract from Green as the Sky is Blue, the new novel by award-winning author Eben Venter

More about the book!

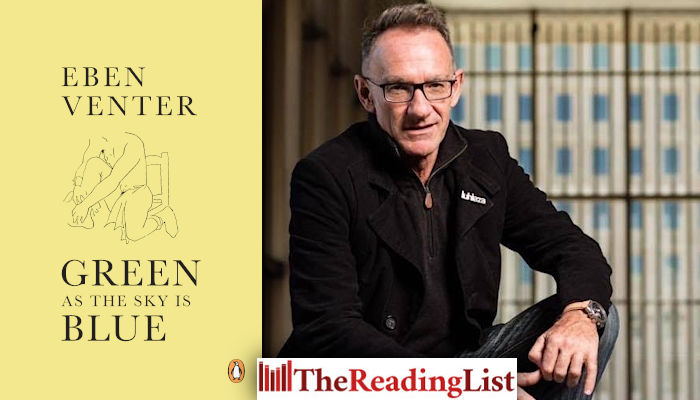

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from Eben Venter’s new novel Green as the Sky is Blue – a bold, unflinching exploration of sexuality, intimacy, and the paradox that lies at the heart of our humanity.

About the book

Simon Avend, a South African living in Australia, can be unruly. He often sets out to exotic destinations, indulging his desires in places like Bali, Istanbul, Tokyo and the Wild Coast.

But along the way unsettling memories arise, of people and also places, especially the cattle farm in the Eastern Cape where he grew up. He approaches a therapist to help him make sense of his past, a process that leads them both on a journey of discovery.

When circumstances bring Simon back to South Africa, he must confront the beauty and bitterness of his country of birth, and of the people to whom he is bound.

Green as the Sky is Blue is a bold, unflinching exploration of sexuality, intimacy, and the paradox that lies at the heart of our humanity.

About the author

Eben Venter’s seven critically acclaimed novels include My Beautiful Death, Trencherman, and Wolf, Wolf. He is also the author of two books of short stories and a collection of columns, and his work can be read in Afrikaans, English, Dutch and German. Raised on a sheep farm in the Eastern Cape, he migrated to Australia in 1986. Over the years he has won numerous awards for his work, including the prominent KykNet-Rapport Prize. Green as the Sky is Blue was written in partial fulfilment of a PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Queensland.

Read an excerpt:

1

My father and I were standing on a wall of rammed earth. He was a robust man, and at that time of the year, brown as the earth beneath him. I was just over ten, and stood there in my short khaki shorts. Above us spread the scorched-blue sky of the Eastern Cape.

‘It’s just the same with us,’ he said.

I looked up, at what? His arm was pointing towards a herd of cattle to the right of the wall. There were two that weren’t grazing, but busy mating.

The bull’s forequarters were raised so that he could mount the cow. His hindquarters, the part that did the thrusting, was solid bulging muscle. She was smaller than him, the cow, with her rippling, shiny cowhide. Excellent condition. I moved away from my father, westerly along the top of the wall. Her eyes, usually so gentle, were bewildered, staring fixedly, until finally, during the last thrusts before she lifted herself and pulled away, terrified.

I looked up at my father. ‘Dis maar net dieselfde tussen ‘n man en ‘n vrou,’ he said once more. It’s exactly the same between a man and a woman. In a tone of voice that closed the matter. It’s how humans copulate, that’s all there is to it.

We continued walking along the wall. It ran in a westerly direction along the foot of the koppies to the hills beyond dotted with stones and bottle-green besembos. When the rains came, so precious on a farm in the north-eastern Cape, the water ran down the koppies to the wall, where it formed a stream, swelling and widening, until it rushed into the dam below, slowly filling it. The dam, built by my father, was the lifeblood of our farm. My father was in every respect an inventive farmer.

‘There was a certain Dr Jan Bonsma,’ my father said as we walked along, sometimes in front of me as the wall narrowed, allowing for only one person. My father’s stride was long, forwardleaning, and he threw his feet outwards.

‘You see, he soon realised that European breeds didn’t do well here. Far too hot for them. Also too dry. They lost weight. Then, over the years, he developed this new breed, mostly Afrikaner, you know the ones. Red, with big horns,’ and with this he raised his arms and stretched them as wide as he could on either side of his head.

‘I know them, Pa,’ I said, annoyed.

He swung around, tilting his head and widening his eyes.

‘Well, the Bonsmara that run on our farm today were bred from Afrikaners, mostly, and then crossed with Herefords and then shorthorns. That’s what you’ve got here today. Just look at those boude,’ – inclining his head to the hindquarters – ‘you can’t compare them with the Nguni, which has suddenly become the in-thing. No ways, they’d never be able to put on the bulk of the Bonsmara.’

My father stopped, pulled out a large white handkerchief from his trouser pocket, laid it carefully on his palm, and with a single jerk pulled out the burr of a boetebos, that weed with oblong seeds that stuck to merino wool, making it useless. The boetebos was a pest even if you didn’t stock merinos – and my father didn’t. He was, as I said, a clever farmer, and had long ago switched to the hardier Dorper breed.

And nothing more about the bull covering the cow. The afternoon was bathed in a milky blue. To our left were the koppies and on our right the grassy veld. Right in front of me, my father’s legs in his farm shorts. The pale stripe in the crease of his knees was the only variation on the brown of his stocky thighs and calves.

This also stuck with me: that swollen bull. His tool, was all I could think of calling the thick thing. It’s what we have and the cow doesn’t. It became funny to me. My father didn’t bother with the bull after saying what he’d said to me. I was the one who watched the bull pull himself out, then lower his head and swing it in slow motion, finished, that was it for him, before walking away from the herd without even looking back. Then he halted, licked his flank with a broad fat tongue and flicked his tail, as his thing slowly retreated into its sheath. He again dropped his head and twisted Karoo bush, small and round and only just higher than his hooves, and nicely curried after the summer rain.

My father didn’t mention the thing about mating again, no elaboration, not even a bit of advice. Never, ever again. That afternoon, as we were walking along the wall of rammed earth, and later, as we descended and headed in a southerly direction, with the koppies now alongside us, and passed through a kloof from where the farmyard with our house and outbuildings became visible, the whole way, I couldn’t get what he’d said about the bull and the cow out of my head. And how it was ‘the same’ with us.

And then years later, as long as it took for me to be comfortable in my skin and walk into a roomful of naked men, say about ten of them, and be one hundred per cent relaxed about it – well, almost – I recalled that afternoon with my father as we walked together along the wall. The flashback occurred in the coastal town of Seminyak on the island of Bali where I was on holiday with my friend Miriam and her lover, an Aboriginal guy called Ralton.

That morning, I woke up on my bed, bigger than any bed I’d ever slept on in Australia, because that’s where I was now living. There were only two bedrooms in our private villa, each with its own bathroom. Double screen doors opened onto a broad veranda, its pillars and walls painted frog-green, and from there steps led into a secluded garden lush with heliconia and frangipani and strelitzia nicolai.

A ceiling fan above my bed moved the tepid air. My skin shone with perspiration and held to the light it reflected the green sheen of the garden outside.

I opened a social network on my phone. The app is designed for hook-ups and its home page showed a gallery of thumbnail pics of guys currently available. Some profile pics didn’t even feature a face or so much as a headless torso, but just an arm, lifted to expose the armpit. If that sort of thing caught your fancy, you’d start a conversation on the strength of an armpit. It was all part of the fun until you showed genuine interest and exchanged twelve or so lines of conversation, and then suddenly everything stopped. Without warning. Just like that. It was simple: the medium is the message; it shapes you, makes you insecure.

You began to torment yourself: you’d said the wrong thing, but what? Maybe it was the pic you sent, too filthy. Or too vanilla. Or maybe you’re totally out of your league. For sure, you’ve revealed too much of yourself. Your self-image is fucked.

I started chatting to a local guy. His name was Dewa. The expression on his profile pic was intense, it wasn’t unfriendly, but nor was it inviting. We chatted politely without sluttishness; sluttishness can be effective, depending on the type you’ve lassoed. I let him know about our villa close to the beach, just off Jalan Petitenget.

Come to my place, he wrote.

I responded inappropriately – the peculiar freedom that the social network allows you: Send me another pic.

While waiting for his response, I moved myself to a cooler spot on the sheet. Soon breakfast would be served on the green veranda, mine on a wooden table right outside my room, Miriam and Ralton’s on a table outside theirs.

The picture downloaded. Dewa was photographed from the back, waist-high in water. He was washing his head and face under a flute of water spurting from a wall. In front of him, close by the fountain, was a row of square banana-leaf baskets with offerings of frangipani and hibiscus and rice kernels.

I typed: I’ll first have breakfast. What time?

You come now.

I must first have breakfast.

Meet at the shop opposite the prison.

Prison? But I knew he was talking about Kerobokan. There was only one prison in Seminyak.

Is it safe? Talk about Kerobokan, and you’re talking about drug smugglers on death row. Exactly that. An Australian woman with straw-coloured hair had at one time been caught as a drug mule; for the past ten years she’s been sitting in Kerobokan. She insists she was duped. Knew nothing about the little load.

Safe. I am a good Bali man. See you. Thank you for the message.

Outside, the houseboy called his three guests to breakfast. He was a Javanese Muslim who had the most beautiful, most effortless smile as he served us. First course was quaintly cut watermelon and lychees and pineapple, sweeter than any Eastern Cape pineapple I’d ever tasted. Then the dark, muddy coffee made there, and finally the main course of nasi goreng. All the while, bare footed, the Javanese guy chatted away, smiling broadly, a master of the art of hospitality.

I told Miriam and Ralton what I planned to do, with just enough detail and nothing more as I knew Ralton was an inquisitive type, always free with that tongue of his. My knapsack was packed with stuff, including my Australian driver’s license as ID.

Miriam beckoned me over, the beautiful granite ring on her third finger glinting, and once there, she pulled me down towards her. ‘Take care of yourself, you’ve got our numbers.’ She kissed me on both cheeks, lightly enough for it not to feel like a farewell-forever kiss.

In the meantime Ralton had waded into the pool in his board shorts. He was quite attractive, with his broad brown shoulders and generous belly, and he was never nasty. Only in the evenings, oiled on whiskey and Bintang beer, which sometimes made Miriam put a hand over his mouth to shut him up.

Next to the pool was a stone sculpture of Ganesh reclining on his side, an open book cradled in the lower part of his curled trunk. I was so excited about my outing, and with the heat clinging to my skin and just warm air to breathe, the sight of peaceful Ganesh made me calmer.

As I was about to leave, Ralton shouted from the pool: ‘You know that social network thing you use?’

‘What about it?’

‘Do you realise the Russians are behind it? Do you know that the Russians are operating here in Bali? They’re behind a lot of businesses here, they pull all the strings.’ He moved across until his shoulders were under the waterfall. ‘I’m telling you.’

‘Now what are you talking about, Ralton?’ The guy still had drink in him from the night before. Miriam was on the veranda, I threw her an appealing glance.

‘I’d be careful if I were you. I’m not telling you this for nothing, you know,’ Ralton said.

‘Look, Ralton. I know this network. It operates worldwide. It’s just for men interested in hooking up with other men. End of story.’

‘This guy you’re seeing this afternoon, are you paying him?’

‘Well, actually, I might, and I don’t mind. I’ve got no issues with it. No one gets hurt. No one is exploited.’

‘It’s not as simple as that. Some of the money goes to the big bosses, and they’re probably Russian.’

‘Don’t be stupid. I’ve used this network often. Many times. It’s just guys wanting to have a good time. Nothing more than that. There’s nothing behind it.’

‘I know what I’m talking about,’ Ralton insisted. ‘I’m telling you.’

‘You haven’t a clue what you’re talking about. See you later.’ I closed the wooden doors to our garden, touching my backpack to make sure I was okay for the outing. I squeezed through the scooters, all parked outside our villa, then kept left to get to Jalan Petitenget at the top of the alley. My heart was pounding from the conversation with Ralton. I was so fuckin annoyed. It was all rubbish.

There was nothing I could do but carry on. Parked scooters were closely packed all along the side of the road, everywhere, some with a bouquet of dried banana leaves tied to their handlebars. At midnight Nyepi would commence, the day of silence, when everything in Bali closes down – the airport and all the shops and ATMs, the lot. All streetlights would be switched off and everybody, all the locals and every single tourist, had to be indoors.

At the top end of Jalan Petitenget I found myself among a crowd of men and women, children and dogs, and tourists taking pictures with their mobiles. Effigies of monsters atop bamboo carriers were being readied for the street procession that preceded Nyepi.

In front of me was a monster three times life-size, standing on one leg with his body bent back, his arm thrown high in the air, with a smaller, pig-like human with three arms balanced on his knee. It was a masterly creation of papier mâché and wood, with a stance that defied gravity. All its features and those of the smaller pig-man were over-sized and gross and beautiful: bushes of armpit hair, flaring nostrils, wildcat whiskers and massive white fangs. Further up the street, bits of other monsters stuck out: more claws and wild hair and feathers. These were the Ogohogoh, creatures from the monsterdom, which surround every village and come down to be among people once a year, only to be burnt again to remove all evil and create harmony between gods and humans, humans and humans, and humans and the environment.

The monster had a sign that read: LPD Seminyak 04, which indicated its sponsor. Boys not older than ten in black T-shirts and board shorts were taking up positions. Their black pomaded hair was parted and combed for the special day. All were laughing and shouting as they gripped onto the bamboo carriers and positioned their tiny boy-shoulders under the heaviest part of the monster high above them. They were all so happy, their black eyes sparkling at the prospect of carrying their monster through the streets of Seminyak.

In the dense crowd I suddenly doubted the wisdom of leaving the procession of monsters and bearer-boys. It was all so magnificent and joyous. And pure. Yet the persistent ticking somewhere inside me pushed me away from the scene. In my head I held the image of Dewa under the fountain, his biceps hard and the curve of his deltoids beautiful as he stood there and washed himself.

The crowd thinned out so I could walk faster, though I main tained the steady pace I’d seen people keep here in the tropics. At times the soles of my Havaianas felt way too thin for the uneven pavements of Seminyak. I was wearing shorts and a dark-blue singlet. I looked up: a thick bundle of electric cables followed the route of the pavement, with a forked bamboo post here and there to hold them up. My Maps app told me to turn right on the main street of Tangkuban Perahu.

Ralton’s load of shit I’d long ago forgotten. I was happily on my way, my knapsack full of sex goodies, a black silicone cock ring, some lubricant and condoms, two generic Viagra tablets, plus two bottles of Bintang beer. And then there was the other intangible stuff I usually take with me to a sex-rendezvous: a deep stirring in my lower belly, but also a happy feeling that I knew my stuff.

At one of those mini-supermarkets that sold everything including generic Viagra, I bought an aloe vera drink sweetened with palm sugar, and gulped down a blue tablet.

In the shade of frangipanis, pruned to form a canopy, sat a group of Balinese men, all in black security uniforms, smoking clove cigarettes. They caught my eye, all of them handsome in some way or another. Do I need transport? No, thank you, I said. Instead, I asked the way to Kerobokan Prison, just to be a hundred per cent sure.

One guy explained the way in detail, not like some locals who assume that strangers are familiar with some or other landmark. My concentration failed. No, all I was aware of was the man’s naked arm touching mine and I realised how easily he’d guess what I was up to. And maybe he already had, because I was so urgent, almost impatient. The Viagra was kicking in, I could feel the flush on my cheeks.

I walked on. My tongue found a cumin seed from the nasi goreng at breakfast and I crushed it between my front teeth, releasing its taste. Then I saw the perimeter walls of Kerobokan prison. A huge sprawling complex with razor-wire like you saw in South Africa rolled out all along the top of the thick walls. Even so, it didn’t seem as intimidating as Pollsmoor Prison near Tokai Forest, which I’d driven past many times while living in Cape Town. Kerobokan Prison was right in the middle of urban life. Close by, a jeans shop sold the American brand Dickies, and over there I saw the heads of people looking out over the half-wall of a warung as they chewed. Right across from the main entrance to the prison was the mini-mart where Dewa would pick me up.

I bought another drink, some orangey thing, over-sweet like all soft drinks in Bali, and waited outside the mini-mart on a bench. By now the heat of all the walking had emptied my mind. I rested the bottle on my leg, emptied my mind even further, smelt stuff that was neither pleasant nor unpleasant and not altogether different from my home back in northern New South Wales – dog hair, and the plumes of tiger grass outside my bedroom window, and sub-tropical mustiness.

Further down the prison wall was another entrance, a smaller one, where a man in a light-blue uniform and a dark-blue beret stood guard. I felt no sense of risk, nothing I was doing or what I was about to do frightened me. I concentrated on Dewa, tried to visualise him on the strength of the pics of the face and body he’d posted. Minutes from now he’d pick me up. He would notice me immediately, few tourists hung out here.

Suddenly, from Kerobokan, from behind that high circular wall with its rolls of razor wire, came the sound of singing. Men droning collectively from deep inside their throats, not unlike Tibetan monks, except that this was terribly sad. In sharp contrast to all the Bali images, the frangipanis behind girls’ ears, a slice of melon perched on the lip of a glass, the kite sellers flying their black pirate-ship kites on Seminyak beach, the copper-brown, half-naked Aussies speeding by helmetless on scooters. I was sit ting across from the underbelly of Bali, I’d seen the Aussies there – falsely accused, as Aussie prisoners always claimed on TV. And then the droning came again, waves of sadness, on and on.

He pulled up next to me, a black scooter and a shiny black helmet. ‘Hello.’ Nothing more. Handsome. I knew how: I swung myself onto the seat behind him, crotch to bum – and no spare helmet. He took off and I hugged the frame on either side of my thighs, but when he charged through his kampong gate, I grabbed onto his waist.

From the moment I stepped off the back of his scooter my senses were on high alert. I was electric with anticipation, ready to touch this guy’s skin, ready for his type of sex, my breathing uneven, as I had no idea how he’d respond to my touch. I didn’t even know whether Balinese Hindus cut their baby boys. There were hardly any words spoken to give me access to him, to his sexual being, his own particular triggers and inhibitions. At the same time, from experience I knew that over-excitement held me back.

Three steps led to the veranda in front of his quarters, a small square building with terracotta roof tiles, separate from similar buildings within the kampong. He led the way without saying anything, completely relaxed. On the skin of my hands: the sensation of grabbing onto his waist. Had to, otherwise I’d have fallen off the scooter. But now the excursion was intimate, on his terms.

Once we began to touch and kiss there’d be no time for thinking, so now, as I entered his room, I tried to prepare myself as I always do at this preliminary stage of the game. Here I am, now. That’s all that matters. The spilling of seed, the outcome, might not even be the climax.

From a long narrow window high up on a wall to the left, light fell onto a table with a two-plate stove and a poster of an MMA boxer right above it. The TV was switched on, at low volume. Seemed to be something like ‘Indonesia’s Got Talent’, broadcast from Java or Sumatra, as the presenter wore a headscarf. The sight of the bar fridge made me take the two Bintangs from my knapsack, both lukewarm by then. Dewa didn’t take a beer.

‘Don’t you drink?’

‘Sometimes.’

He cleared the double bed of stuff, took his shirt off, then shook a cigarette from a packet. I watched his biceps curl into a smooth bulge as he lit up.

‘Kulkas,’ I said, pointing at his bar fridge.

‘You know the word?’

‘Yes. In the seventeenth century, slaves were imported from Batavia to the Cape of Good Hope, and many of their words blended into our language. Asbak,’ I said.

He laughed, handing me the ashtray. Such a handsome guy.

I unpacked the rest of the goodies from my knapsack, took off my shirt and jeans and stood there, with just my Bonds jocks on. Then I turned my back on him to fit my cock ring in a single swift movement, slipping both balls and cock through the black silicone ring and adjusting it to where it would remain hanging for the duration of the game.

Dewa seemed fine with what I was doing, he squatted there, fiddling with his phone charger. But when he got up, I approached from behind and slipped my hands under his armpits, into the secrecy of his pitch-black, slightly coarse armpit hair, its clamminess on the palms of my hands, and I bent down to the curve between his neck and shoulder, he was centimetres shorter than me, and kissed him there with my tongue and the insides of my open lips.

He surrendered under me, I could tell by his breathing and the way his back sank against my hairy chest. I held him away from me so that I could look at his back with its coppery unblemished skin taut across the muscles. Then I ran my right hand all along his spine, sunken so as to accentuate the twin blades of his back, and again he gave under me, all the way, down, as my hand was sliding onto the curve where his buttocks started, to his crack, the secret fine hairs there, black and sweaty and slicked up with what my hand offered him.

The beauty of this guy’s back, his male body – I paused, breathless. From outside the room came the patter of chickens and children, traffic; then I continued. I claimed him, took him for myself, the object of my particular sort of desire.

No, I wasn’t ready yet. A slow starter, and it had taken me years to be comfortable with that too. So I moved away from him, lifted the tube of lubricant, a silky Australian brand I’d packed for the trip, worked some onto myself without removing my jocks. Dewa pulled his underpants off, white Calvin Klein-types, and lit another cigarette. That break was a gift, and I relaxed, in my hand I was there, ready for my Bali-fuck, my gorgeous, smooth-skinned Balinese guy.

His teeth, chalk white against the dark skin of his face, came between our kissing but didn’t put me off – he measured out his breathing with tiny bites. And all the while, as I held his torso, his whole body, as close to mine as strength allowed, my index and middle finger tucked inside him to retain the closeness, I was dimly aware of his room, the pale-green light coming off the walls, the foreign language on TV, his clothes, folded ones on an open shelf and used ones on the tiled floor, and other objects, a golden Chinese good-luck kitten with its waving paw, cheap magazines, all the extensions of his kind of life in Bali, extensions of this body against mine, which I could know without him or me having to say anything.

He went down on his knees on the edge of the bed and gave himself to me like an animal and, once I was inside him, he jacked me up of his own volition, an action that enfolded me, ate me as he built up his rhythm, becoming a fast pummelling. From gripping between the muscular buttocks to sliding my hands along his flanks to going down on him and licking a vertical path along his spine, fragrant now, I tried to hold back coming until I knew for sure I needed to pull out for a moment or I was going to blow.

I did that, I held back. And I raised his body by slipping my arm under his chest and kissed him full-on, harder than before, the kiss of a man high on satisfaction, now and in the immediate future, while I was already working out my next position with him.

We smoked, and I drank Bintang and he drank some water from a one-litre plastic bottle.

I walked to the bathroom at the back.

‘There is only cold water,’ he said.

It was tight for a bath, a square-shaped trough filled with cold water to the three-quarter mark, with a small red bowl floating on top for scooping and rinsing. There was a bottle of shampoo specially for dark hair, and some body wash. From a small window, high up, like the one on the left wall of his room, came a shaft of hot light. In the right-hand corner was a squat-toilet with a water bucket. On the tiled floor to one side of the toilet stood a roll of one-ply paper.

First I rinsed my face, then scooped water into the red bowl, rinsed myself properly, and chucked the used water down the hole of the toilet. There was no towel. I just shook the excess water off my face, legs and arms, and walked back to Dewa’s room.

He was squatting against the wall. On his lap a blue plastic plate with food that he scooped up with his right hand. It looked like egg noodles coloured with turmeric root and chopped something or other, maybe chicken. He didn’t offer me anything, which was fine with me. My body felt horny, not much else registered.

I turned the fan towards the bed, and after he wiped his mouth with the back of his arm, finished, I said: ‘Come here, lie on your back.’

I began by squatting over his chest, almost touching him, running my fingers through his straight black brush-cut, and moved myself backwards and forwards over the taut skin of his chest, bent down and kissed him, first in the curve of his neck, then on his mouth, then I lifted his right arm and nuzzled his armpit – its hair so distinctly different to the fine fuzz above his navel – the smell sweetish and warm and young, and afterwards sweet-sourish. The intimate nudge of my mouth in the pit of his arm excited him. He grabbed me by the buttocks and raised himself so that I could enter without resistance.

After a while I lifted him even higher so as to get to him while still squatting, displacing the weight to my heels and giving momentum to my lower back and bum, which gave me the opportunity to work harder.

After he had washed himself, I went in and did the same, again. Glimpsing myself in the mirror, I appeared rejuvenated, enthusiastic.

I stepped out of Dewa’s quarters onto the small veranda. The courtyard inside the compound looked different to when I arrived. The chickens were still scurrying around and the dogs were just as lethargic, the fighter roosters gasping in their overturned baskets of plaited rattan – rottang in Afrikaans – children playing, women doing household things, and there was the smell of cloves and traffic fumes and grey water. All of these filled my senses, each one of them real, as they were, but without the overlay of lust, as when I’d arrived on the back of Dewa’s scooter and the roosters inside their baskets seemed like angry monster birds.

‘I’ll drive you back to your villa,’ Dewa said. ‘When will you come again?’ I handed him 300 000 rupiah. From our online chat I knew he expected this amount, and I had the money ready.

‘I’m not sure. Did you like it?’

He liked it, I could tell. AUD30, it was nothing. A consensual deal.

‘Yes. Sangat baik.’ His baik sounded like baie in Afrikaans. I hugged him hard but he didn’t reciprocate. Already he’d assumed the distance I sensed since we first chatted on the social network.

I slipped my Havaianas on. As I swung onto the back of his scooter I looked down at my feet which, like the rest of my body, were glistening with fresh sweat after the wash-down.

At that moment I remembered my father and me standing on the wall of rammed earth, and the bull mating with the cow, and the thing he’d said about this. There was no apparent trigger to bring on the memory. It just came, and that was it. There was no similarity between that late Seminyak afternoon in Dewa’s compound and my family’s faraway Eastern Cape farm.

By early evening I was back in our private garden. I closed the wooden doors behind me; I’d really achieved something, I felt. My body exhausted, my mood exuberant. The clusters of frangipani gave off their peach-and-spices scent. Miriam and Ralton walked up, drinks in hand.

‘Mmm,’ Ralton said, ‘nice warm hand,’ as he shook mine. He was drunkish. He lay the back of his hand against my chest. ‘You’ve been busy, I can tell.’

They were pleased to have me back in one piece. Ralton with his tall glass of brandy and Coke didn’t dare to say anything more about Russian pimps working social media. Instead, he offered to roll me a cigarette.

By midnight, Seminyak had gone silent. Also, it was dark moon on the calendar. In the traditional Hindu home everyone except children and the sick should now abstain from food and drink. You were not supposed to say anything; this was a time to demonstrate self-control and to reflect on your values.

‘Come with me, I want to have a quick look. Just to see what it’s like out there,’ Miriam said.

We followed the stepping stones through our dark garden and unlocked the wooden doors. Outside, none of the street lamps were on, not a soul to be seen. With my phone on torch mode, I lit the way to the alley. The shape of a dog was moving towards us. We stopped. So did the dog.

‘There!’ Miriam tugged at my arm.

Where the alley ran into Jalan Petitenget we saw the pecalang, the guards with their powerful torches patrolling the streets, making sure everybody was inside.

We hurried back to the garden and shut the wooden doors behind us. Miriam was still holding my arm. I pulled her to me, into my chest, and held her there, her long curly hair against my face, the skin of her bare shoulders under my hands. Then we let go of one another, stepped carefully along the path until we reached the veranda, and the glow of a cigarette revealed where Ralton was seated.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Eben Venter Green as the Sky Is Blue New books New releases Penguin Random House SA