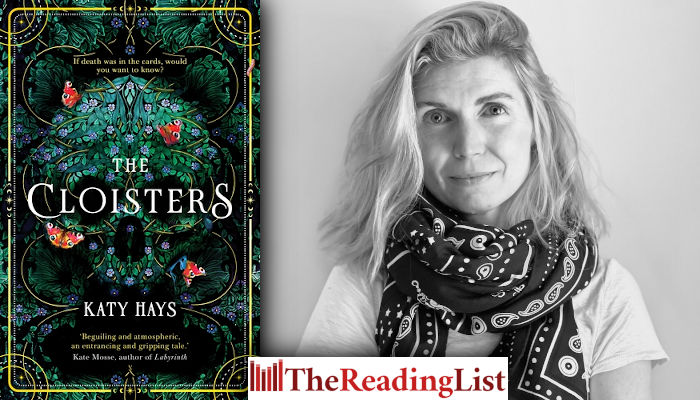

Read an excerpt from The Cloisters by Katy Hays – a gripping debut that will keep you on the edge of your seat

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an extract from The Cloisters, the sinister, atmospheric new novel by Katy Hays.

About the book

In this ‘sinister, jaw-dropping’ (Sarah Penner, author of The Lost Apothecary) debut novel, a circle of researchers uncover a mysterious deck of tarot cards and shocking secrets in New York’s famed Met Cloisters.

When Ann Stilwell arrives in New York City, she expects to spend her summer working as a curatorial associate at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Instead, she finds herself assigned to The Cloisters, a gothic museum and garden renowned for its medieval art collection and its group of enigmatic researchers studying the history of divination.

Desperate to escape her painful past, Ann is happy to indulge the researchers’ more outlandish theories about the history of fortune telling. But what begins as academic curiosity quickly turns into obsession when Ann discovers a hidden 15th-century deck of tarot cards that might hold the key to predicting the future. When the dangerous game of power, seduction, and ambition at The Cloisters turns deadly, Ann becomes locked in a race for answers as the line between the arcane and the modern blurs.

A haunting and magical blend of genres, The Cloisters is a gripping debut that will keep you on the edge of your seat.

Read the excerpt:

PROLOGUE

Death always visited me in August. A slow and delicious month we turned into something swift and brutal. The change, quick as a card trick.

I should have seen it coming. The way the body would be laid out on the library floor, the way the gardens would be torn apart by the search. The way our jealousy, greed, and ambition were waiting to devour us all, like a snake eating its own tail. The ouroboros. And even though I know the dark truths we hid from one another that summer, some part of me still longs for The Cloisters, for the person I was before.

I used to think it might have gone either way. That I might have said no to the job or to Leo. That I might never have gone to Long Lake that summer night. That the coroner, even, might have decided against an autopsy. But those choices were never mine to make. I know that now.

I think a lot about luck these days. Luck. Probably from the Middle High German glück, meaning fortune or happy accident. Dante called Fortune the ministra di Dio, or the minister of God. Fortune, just an old-fashioned word for fate. The ancient Greeks and Romans did everything in the service of Fate. They built temples in its honor and bound their lives to its caprices. They consulted sibyls and prophets. They scried the entrails of animals and studied omens. Even Julius Caesar is said to have crossed the Rubicon only after casting a pair of dice. Iacta alea est—the die is cast. The entire fate of the Roman Empire depended on that throw. At least Caesar was lucky once.

What if our whole life—how we live and die—has already been decided for us? Would you want to know, if a roll of the dice or a deal of the cards could tell you the outcome? Can life be that thin, that disturbing? What if we are all just Caesar? Waiting on our lucky throw, refusing to see what waits for us in the ides of March.

It was easy, at first, to miss the omens that haunted the Cloisters that summer. The gardens always spilling over with wildflowers and herbs, terra-cotta pots planted with lavender, and the pink lady apple tree, blooming sweet and white. The air so hot, our skin stayed damp and flushed. An inescapable future that found us, not the other way around. An unlucky throw. One that I could have foreseen, if only I—like the Greeks and Romans—had known what to look for.

CHAPTER ONE

I would arrive in New York at the beginning of June. At a time when the heat was building—gathering in the asphalt, reflecting off the glass—until it reached a peak that wouldn’t release long into September. I was going east, unlike so many of the students from my class at Whitman College who were headed west, toward Seattle and San Francisco, sometimes Hong Kong.

The truth was, I wasn’t going east to the place I had originally hoped, which was Cambridge or New Haven, or even Williamstown. But when the emails came from department chairs saying they were very sorry_._._. a competitive applicant pool_._._. best of luck in your future endeavors, I was grateful that one application had yielded a positive result: the Summer Associates Program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A favor, I knew, to my emeritus advisor, Richard Lingraf, who had once been something of an Ivy League luminary before the East Coast weather—or was it a questionable happening at his alma mater?—had chased him west.

They called it an “associates” program, but it was an internship with a meager stipend. It didn’t matter to me; I would have worked two jobs and paid them to be there. It was, after all, the Met. The kind of prestigious imprimatur someone like me—a hick from an unknown school—needed.

Well, Whitman wasn’t entirely unknown. But because I had grown up in Walla Walla, the dusty, single-story town in southeastern Washington where Whitman was located, I rarely encountered anyone from out of the state who knew of its existence. My whole childhood had been the college, an experience that had slowly dulled much of its magic. Where other students arrived on campus excited to start their adult lives anew, I was afforded no such clean slate. This was because both of my parents worked for Whitman. My mother, in dining services, where she planned menus and theme nights for the first-year students who lived in the residence halls: Basque, Ethiopian, asado. If I had lived on campus, she might have planned my meals too, but the financial waiver Whitman granted employees only extended to tuition, and so, I lived at home.

My father, however, had been a linguist—although not one on faculty. An autodidact who borrowed books from Whitman’s Penrose Library, he taught me the difference between the six Latin cases and how to parse rural Italian dialects, all in between his facilities shifts at the college. That is, before he was buried next to my grandparents the summer before my senior year, behind the Lutheran church at the edge of town, the victim of a hit-and-run. He never told me where his love of languages had come from, just that he was grateful I shared it.

“Your dad would be so proud, Ann,” Paula said.

It was the end of my shift at the restaurant where I worked, and where Paula, the hostess, had hired me almost a decade earlier, at the age of fifteen. The space was deep and narrow, with a tarnished tin ceiling, and we had left the front door open, hoping the fresh air would thin out the remaining dinner smells. Every now and then a car would crawl down the wide street outside, its headlights cutting the darkness.

“Thanks, Paula.” I counted out my tips on the counter, trying my best to ignore the arcing red welts that were blooming on my forearm. The dinner rush—busier than usual due to Whitman’s graduation—had forced me to stack plates, hot from the salamander, directly onto my arm. The walk from the kitchen to the dining room was just long enough that the ceramic burned with every trip.

“You know, you can always come back,” said John, the bartender, who released the tap handle and passed me a shifter. We were only allowed one beer per shift, but the rule was rarely followed.

I pressed out my last dollar bill and folded the money into my back pocket. “I know.”

But I didn’t want to come back. My father, so inexplicably and suddenly gone, haunted every block of sidewalk that framed downtown, even the browning patch of grass in front of the restaurant. The escapes I had relied on—books and research—no longer took me far enough away.

“Even if it’s fall and we don’t need the staff,” John continued, “we’ll still hire you.”

I tried to tamp down the panic I felt at the prospect of being back in Walla Walla come fall, when I heard Paula say behind me, “We’re closed.”

I looked over my shoulder to the front door, where a gaggle of girls had gathered, some reading the menu in the vestibule, others having pushed through the screen door, causing the CLOSED sign to slap against the wood.

“But you’re still serving,” said one, pointing at my beer.

“Sorry. Closed,” said John.

“Oh, come on,” said another. Their faces were pinked with the warm flush of alcohol, but I could already see the way the night would end, with black smudges below their eyes and random bruises on their legs. Four years at Whitman, and I’d never had a night like that—just shifters and burned skin.

Paula corralled them with her outstretched arms, pushing them back through the front door; I turned my attention back to John.

“Do you know them?” he asked, casually wiping down the wood bar.

I shook my head. It was hard to make friends in college when you were the only student not living in a dorm. Whitman wasn’t like a state school where such things were common; it was a small liberal arts college, a small, expensive liberal arts college, where everyone lived on campus, or at least started their freshman year that way.

“Town is getting busy. You looking forward to graduation?” He looked at me expectantly, but I met his question with a shrug. I didn’t want to talk about Whitman or graduation. I just wanted to take my money home and safely tuck it in with the other tips I had saved. All year, I’d been working five nights a week, even picking up day shifts when my schedule allowed. If I wasn’t at the library, I was at work. I knew that the exhaustion wouldn’t help me outrun my father’s memory, or the rejections, but it did blunt the sharp reality of it.

My mother never said anything about my schedule, or how I only came home to sleep, but then, she was too preoccupied with her own grief and disappointments to confront mine.

“Tuesday is my last day,” I said, pushing myself away from the bar and tipping back what little was left in my glass before leaning over the counter and placing it in the dish rack. “Only two more shifts to go.”

Paula came up behind me and wrapped her arms around my waist, and as eager as I was for it to be Tuesday, I let myself soften into her, leaning my head against hers.

“You know he’s out there, right? He can see this happening for you.”

I didn’t believe her; I didn’t believe anyone who told me there was a magic to it all, a logic, but I forced myself to nod anyway. I had already learned that no one wanted to hear what loss was really like.

Two days later I wore a blue polyester robe and accepted my diploma. My mother was there to take a photograph and attend the Art History department party, held on a wet patch of lawn in front of the semi-Gothic Memorial Building, the oldest on Whitman’s campus. I was always acutely aware of how young the building, completed in 1899, was in comparison to those at Harvard or Yale. The Claquato Church, a modest Methodist clapboard structure built in 1857, was the oldest building I had ever seen in person. Maybe that was why I found it so easy to be seduced by the past—it had eluded me in my youth. Eastern Washington was mostly wheat fields and feed stores, silver silos that never showed their age.

Categories Fiction International

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Katy Hays Penguin Random House SA The Cloisters