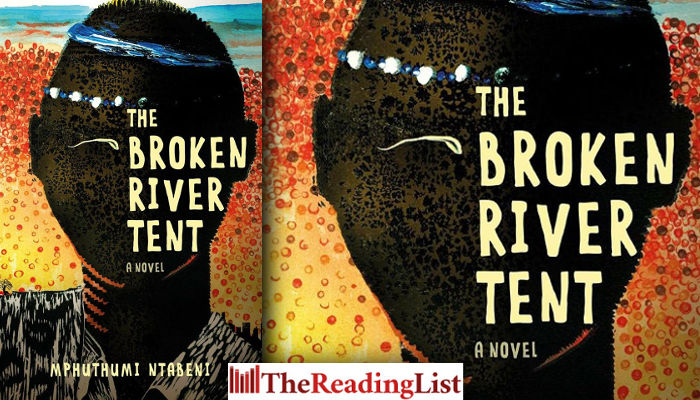

Read an excerpt from Mphuthumi Ntabeni’s The Broken River Tent, a novel about the life and times of the Xhosa chief Maqoma

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an extract from The Broken River Tent, the debut novel by Mphuthumi Ntabeni.

The Broken River Tent is set in the time of Maqoma, the Xhosa chief at the forefront of fighting British colonialism in the Eastern Cape in the 19th century.

It is an entrancing novel that marries imagination with history.

The Broken River Tent is out now from BlackBird Books.

Read an excerpt:

The River Tent is Broken

‘That’s strong enough to float an egg.’

Siya handed Phila a cup of black coffee and sat down opposite him at the kitchen table. He took a swipe of it. ‘Aah! Heaven.’ The strength of the brew agreed with him. Since he’d arrived at the family house in Queenstown, they had been talking about everything except the death of their father. This made him feel implicated, but in what he had no idea.

Something in his father’s body had burst. All he could think about was that the shit had hit the innards. Phila felt crude in thinking about it along those lines, but he was never of the euphemistic lot. He didn’t care because he felt whatever burst in his father was bobbing towards his own innards anyway. But that is not the kind of conversation you have with your sibling on the morning you are planning to see your dead parent at the mortuary.

‘I was wonderfully amazed to see the apricot tree is still there!’

‘Yep. And it still yields fruit in due season.’

Siya was usually taciturn so Phila tried not to read anything from her brief sentences. There were hanging issues neither of them was in a mood for at that moment. Besides, neither knew where to start, or what the point would be of plucking hanging issues instead of letting the fruit fall down to be manure, or poison. The Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski talked about the ‘law of the infinite’, saying that an infinite number of explanations can be found for any given event. Some clever professor whose lecture Phila had attended in Berlin connected this with what psychologists christened ‘hindsight bias’: the tendency to regard actual outcomes as more probable than alternatives. The whole thing hadn’t really made sense when Phila read it, but now he was either more gullible because he wanted to avoid thinking about his dead father, or else the bulb was getting some electricity. His hindsight bias was always in suspecting he could have done something to change the course of things had it not been for his proclivity to leave well alone. Could he have been more attentive to the needs of his girlfriend? Could he have suspended his moral judgement to save his firm, for ‘the greater good of all’? Could he have made time to visit his father and talk things out? Could he have, could he have … ? What could he have?

Primo Levi survived the brutal torture of the Nazis in Auschwitz, and had spent most of the rest of his life writing against revenge and refusing to be a victim. Then he’d jumped off the third storey of a building to kill himself when he was sixty-seven years old – oddly enough, the same age as Phila’s father. Put your hindsight theory to that and shove it, he thought. We are a mystery mostly to ourselves. What we accept with our heads makes for our necessary fall when the heart has rejected.

Everything is falling, and I’m included in it, he thought as he looked at his sister’s beautiful face. Made him admit that his father gave them good genes. Just so we’re clear about things: no medically trained person dies of a perforated ulcer by accidental neglect. Even the ways by which we fall come from our agency, conscious or otherwise, was Phila’s last thought.

The following day they travelled to their father’s rural home, seventy kilometres east of their hometown. The burden of the hours came with Phila. It had been close to three decades since he had seen the place. He trained his eye on the passing villages, the sparse, abstract shoreline of brown and turquoise hutments against the lion’s mane coloured grass. The mountains, bleak and untamed, still possessed a haunted look. Progress and consumerism had caught up with the area since the change of government from the apartheid regime. Bridges had been built over rivers; electricity installed for those who could afford it; purified water coming out of installed communal taps, free of charge. Things were changing for the better, he thought, but what, he couldn’t help wondering, would Dr Samuel Johnson have had to say about it – Johnson had been of the opinion that change of governments makes no difference to the happiness of ordinary people.

The earth still heaved towards the craggy cliffs, building up to green mountains where the river snaked in a labyrinth to create the valleys where, for six generations now, his forefathers had lived and planted their fields. From there the road can take you no farther, what with the prince of the mountains, Lukhanji, standing in your way and casting its shadow over everything. The mountain sent water down the sedimentary donga, creating streams that acted as bloodline arteries for the valleys. This was where his father had hidden his defeated life, here among scrawny-looking sheep and an austere cluster of rondavel huts. This lonesome hill, with its echoes of the muffled screams of the dying river.

Traditionally, it was Phila’s home also.

It was evening when they arrived, the day before their father’s funeral, and the activity was already widespread. Bundles and bundles of wood lay around. A bull was being slaughtered at the kraal, because his father was a first-born, which traditionally mandates a bull falls with him. Pots of samp, cabbage and potatoes were boiling at the hearth. And the last containers zamarhewu were being brewed and distilled. Everyone had something to do but Phila. When he wanted to lend a hand he was directed away to something else, mostly some less arduous task. He became used to the dismissive gesture. ‘This is not for delicate hands, yezifundiswa.’

Being classed with the namby-pamby educated class irritated him. But he was clumsy in basic things like logging, keeping a straight line behind a cattle-drawn plough, or milking cows. He walked from kraal to shed, hearth to kitchen, pen to graveyard, looking for something to be useful at. No one required his help. His only usefulness was in driving a car or tractor to fetch the elderly. Whenever he met up with his elders Phila had a strange inclination to act more sombre than he actually felt in order to look for their commiseration. He felt he had to demonstrate to them the fact that he loved his father. Internally this made him feel like an impostor. Of course he felt loss for his father, vague as it might have been. He suspected it to be more about sentimentality, his tendency to idealise loss or absence. Absence does not get more permanent than death.

He walked past the graveyard, thinking how the Jewish culture was better in these situations. Everyone was allocated their own role to play. As children they would be obligated to visit the graves of their parents; to frequently recite prescribed memorial prayers at the graveside. Phila felt this prescribed mode of mourning ritualised loss better, giving it direction, perhaps even purpose.

He went on a gadabout riverward, to ponder things out. Standing on the river bank, in stilled attention, listening to the sounds of his childhood, remembering how he and his cousin used to trap crabs here when he was about seven, open their ‘purses’ to look for the coins they were told they contained. A line from TS Eliot’s ‘The Fire Sermon’ trespassed to his mind:

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

Clutch and sink into the bank. The wind

Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

And there came his cousin, driving a cart pulled by two oxen, wearing gumboots, chaps on top of his dirty jeans and a tattered checked shirt, and with a gleeman song on his mouth. A suede hat sat precariously on his head. They greeted. Talked about days gone by. But the natural innocence of youth had been lost even between them, leaving behind awkward silences. His cousin was the one who knew all the cattle by name and colour, not just number like the rest of them. He was the one who knew what to do when the rains didn’t come to avoid the crops failing or the stock dying. He was the one who knew what his father thought in his last days as the ulcer bore into his innards. Phila knew in his heart of hearts that his cousin should be the one to inherit all that was left behind by his father. After all, according to the messiah, the meek inherit the earth.

‘You remember, mzala, how we used to fish the rivers?’ his cousin asked as he sat down, lighting his dagga pipe.

‘I was just thinking about that. We used reed poles to tie the fishing lines. And no reel. I remember how once the pull slashed your palm …’

‘Indeed!’ His cousin extended his hand for Phila to examine. The scar was still there, smaller than Phila was imagining it in his head, but nasty all the same.

‘What is happening to the river? Why is it dwindling, drying up?’

‘They dammed it for water for the town folks,’ his cousin answered without much concern. Phila, on the other hand, felt anger. They talked about when the dam was built by the apartheid regime with no consideration given to village people. ‘The fish of our youth died with the river,’ his cousin said. As he got up to continue on his way with the cart, Phila wondered if this was one of the reasons black people were angry, burning and damaging things – because they were looking for their youth.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags BlackBird Books Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media Mphuthumi Ntabeni The Broken River Tent

You must log in to post a comment

That’s it I’m getting myself a copy ☺️

Cwayita