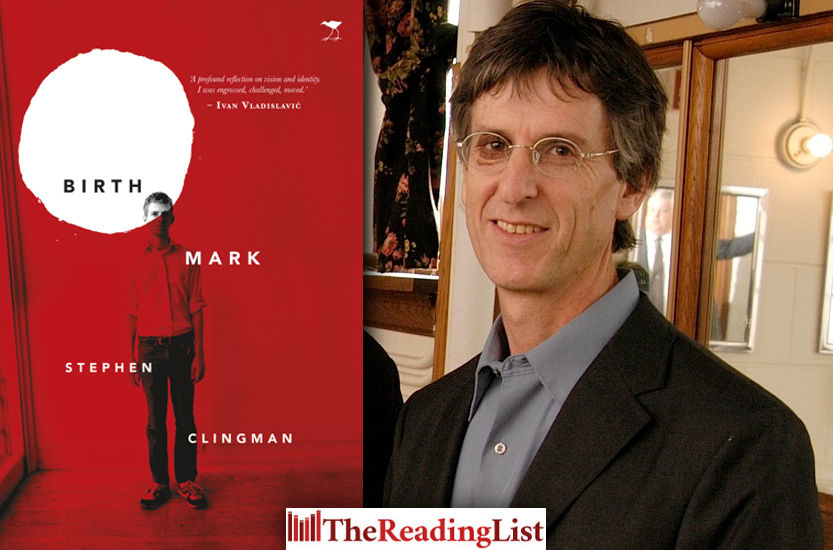

‘Johannesburg is both a place that I know and don’t know’: An interview with Stephen Clingman about his memoir, Birthmark

Stephen Clingman chats to The Reading List about his memoir, Birthmark, published by Jacana Media.

The Reading List: Thank you very much for the interview, Stephen.

Stephen Clingman: It’s my pleasure; thanks for your interest.

The Reading List: As a South African memoir, your work has been compared to the autobiographical novels of JM Coetzee—Boyhood and Youth—as well as Jacob Dlamini’s Native Nostalgia. Do you enjoy the genre, and did you read widely within it before beginning to write your own?

Stephen Clingman: I had read Coetzee’s memoirs and Jacob Dlamini’s as well, and further back in time there were other books that had affected me, such as Nadezhda Mandelstam’s Hope Against Hope. I wouldn’t say I have a special affinity for autobiographies or memoirs as such, but what does interest me are works that explore the dividing line—which is also a connecting line—between fiction and non-fiction. A work of memory, which is what Birthmark is, inevitably connects the fictive and non-fictive, and those that do so consciously seem to me most interesting of all.

The Reading List: Before Birthmark, you published a book on Nadine Gordimer, and a biography of Bram Fischer, which won the Alan Paton Award. The research behind these books is clear, but did you find you had to do research on your own life and times for your memoir?

Stephen Clingman: One of the pleasures of writing Birthmark is that it involved virtually no research at all. This was the story of what I remembered, as I remembered it. There were one or two moments where I needed to check on things, especially where others were involved, or in one case to avoid the possibility of libel, but generally very little of that was required. And of course there were no footnotes—a great relief after the rigours of academic work.

The Reading List: With a novel, readers often assume both that the story is made up and that at least some of it is autobiographical—such is the nature of fiction. With autobiography, readers assume the story is the truth, when in fact the writer is still controlling what goes into the narrative and what is left out. Was this something you were thinking about when you were writing the book?

Stephen Clingman: Yes, this was something I was very much conscious of. There is the question, which I’ve mentioned already, of how the fictive and non-fictive coalesce in the work of memory. But beyond that is the question you allude to, of how far one controls what is admitted to memory, at least publicly. That involves an implicit question of censorship: am I expurgating what I am prepared to say? I think any honest memoirist would have to search himself or herself quite carefully on that score. But beyond that is yet an even more taxing question: how far is my memory censoring itself, without my knowledge, as it were? Here one reaches the boundaries of conscious awareness, and realises the intrinsic limits of the self knowing itself. A good book will explore this too; I hope Birthmark does.

The Reading List: Did you find the grammatical structure of the book—past and present tense, third person and first person—tricky to manage? Why did you decide to write the book in this way?

Stephen Clingman: It was tricky in parts, where the transitions were hard to manage. But in other respects it flowed quite easily, and the logic, to me at least, was clear. When the self remembers the self—say a much younger version of the self—the result is something that is both subject and object. I was that person over there, and so the third-person narrative seems quite natural. But I am still the one remembering, and there is still some continuity with the person I once was: hence the first-person text. Some memories come with an intense immediacy: thus, the present tense, as I relive the moment. Some are more distant in time and experience, and so the past is more fitting. These flows of memory have their philosophical components—exactly what the relations are between subject and object, past and present, in the continuous, and yet in some ways discontinuous, self.

The Reading List: Your descriptions of military service were described by Ivan Vladislavić as ‘dark comedy’. Was it important to you to include humour in your work?

Stephen Clingman: Humour is very important to me. Otherwise, especially in a work of memoir, one takes oneself too seriously. Humour is a sign of perspective; and it is also a principle of human resilience. As for the army, to me it was intrinsically absurd, so the dark comedy was the only way to describe it.

The Reading List: The book includes some intimate observations of Johannesburg. Have you found you view the city differently since you moved to the United States? Is it easier to observe from a distance?

Stephen Clingman: Distance may lend objectivity, but after many years away there is the sense that Johannesburg is both a place that I know and don’t know. There is a kind of personal archaeology for me here: layers of the city that are familiar that come from an earlier time, and more recent layers that I would have to spend real time excavating to discover. It is a kind of reverse archaeology, if you like: the past is more present to me than the present is. But I think it is also appropriate to come at this with a genuine sense of humility. People here on the ground know so much more than I do; their lived experience is something I can only touch on tangentially. Primarily, the book was exploring a Johannesburg of the past and of memory. As for the present, along with the challenges and sheer intensity of Johannesburg, I have to say that I really admire the energy and intrinsic creativity of the city.

The Reading List: When the book was launched at WiSER, you said you often tell your students not to allegorise in their work, implying that you were avoiding that in your own work. Could you expand on that a little?

Stephen Clingman: Allegory, I feel, is a short cut to meaning: you measure structure ‘A’ against structure ‘B’ and draw direct and clear lines of correspondence between them. Clarity, however, is gained through the reduction of meaning to that correspondence. The meanings of good writing, and good art in general, I feel are both more fleeting and richer than that. If you close down meaning at the start, you also close yourself to the ongoing possibilities of discovery that can emerge with time, with altering perspectives, with the changing questions you can ask of both yourself and the text. When you settle for allegory, you stop that process. This is a long-hand way of saying that in Birthmark I wanted to be quite resistant to allegory, though some of the key themes—of vision, of perspective—run throughout.

The Reading List: You’ve said that Birthmark was a book you discovered while you were writing it. Can you explain a little about what you meant by that?

Stephen Clingman: As you will see from the book, it is written in short, numbered segments. In writing it, I had two basic rules. One was that each segment should be no longer than three to five pages. The second was that each should end up somewhere other than where it began. In other words, each segment was like a mini-journey of associative memory, as one thing led to another. That is also true of the book as a whole: the principle of association and journey applies throughout. Intrinsically, therefore, the book had to be one of discovery: I discovered where I was going in the writing itself. The other image I had for the book was that of the hologram. The successive segments build up a three-dimensional picture across time and space, in different layers and from different angles. The hologram in that respect is like the cumulative angles and perspectives of memory. But like memory, if you try to grab the hologram, or hold on to it, you find it is only an illusion, an image in space. It disappears in your hands.

The Reading List: Did you keep to a routine or schedule while writing the book?

Stephen Clingman: Yes, I did. I would write one segment a day, and sometimes two if I was really flying. When I finished each one, I had no idea where the next one would begin. But when I woke up the following morning, there it was, and I just started. As I say, it was an associative process.

The Reading List: You’ve mentioned that while you were writing, you had no intention of publishing the finished result. What changed your mind? And did the plans to publish the book make you reconsider any parts of what you’d written?

Stephen Clingman: My first objective in writing the stories was simply to record aspects of my life, and the life I once lived with others in Johannesburg. As someone now living in the US, I thought that I didn’t want the past I knew to disappear. If my daughters, or in due course their children, wanted to know what life was like for their parents or grandparents, this perhaps would tell them something about it. This need to record is perhaps common to many migrants—the anxiety around loss, the relationship between the ‘here’ and the ‘there’. For me, it was also a matter of personal exploration: to treat myself as a character and say, what went into the making and shape of that character? If you can begin to understand one life, or to explore it, you realise that that is a reality you can multiply, essentially by all the people in the world. We all have our ‘birthmarks’—accents of birth that shape and make us. As the process went on, I then realised that what I was writing had the makings of a book. Writing it not as a book perhaps released some of the pressure; the discovery that it might be one was quite exciting.

The Reading List: Finally, what have you been reading yourself recently? Any books to recommend?

Stephen Clingman: Partly because I have been interested recently in issues prompted by the refugee crisis in so many parts of the world, I have been drawn to books either closely or tangentially connected with issues of the fugitive. Caryl Phillips is someone whose work is often connected in that way; his recent book, The Lost Child, includes among other things, a reinterpretation of the story of Wuthering Heights, as well as of the origins of Heathcliff. I’ve also started reading what looks like an amazing book by Jenny Erpenbeck, called Go, Went, Gone, which involves refugees in Germany. Then, partly because I taught a course last semester on spy fiction, I’ve been reading lots in that area—much Le Carré, for instance. There is something about duplicity and the doubleness of experience, as well as issues of decoding the world from the inside, that seems to absorb me. That too is distantly a Birthmark experience.

Categories International Non-fiction South Africa