12 myths about rape – read an excerpt from Rape: A South African Nightmare by Pumla Dineo Gqola

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Rape: A South African Nightmare by Pumla Dineo Gqola.

Why has South Africa been labelled the ‘world’s rape capital’? What don’t we as South Africans understand about rape?

In Rape: A South African Nightmare, Gqola unpacks the complex relationship South Africa has with rape by paying attention to the patterns and trends of rape, asking what we can learn from famous cases and why South Africa is losing the battle against rape.

This highly readable book leaps off the dusty book shelves of academia by asking penetrating questions and examining the shock belief syndrome that characterises public responses to rape, the female fear factory, boy rape, the rape of Black lesbians and violent masculinities.

The book interrogates the high profile rape trials of Jacob Zuma, Bob Hewitt, Makhaya Ntini and Baby Tshepang as well as the feminist responses to the Anene Booysen case.

About the author

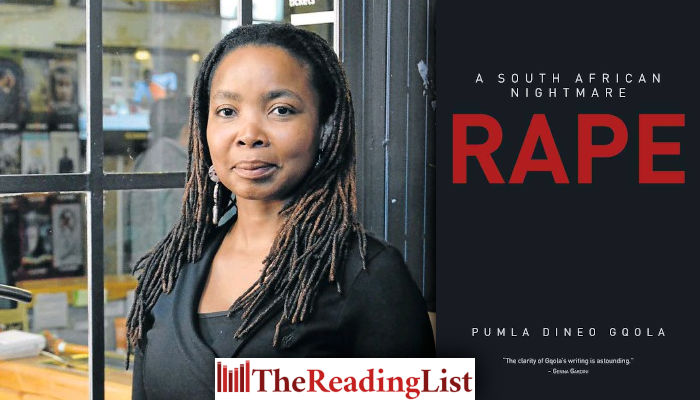

Gender activist, award-winning author and professor of African Literature at Wits University, Pumla Dineo Gqola has written extensively for both local and international academic journals. She is the author of What is Slavery to Me?, A Renegade Called Simphiwe, Rape: A South African Nightmare and Reflecting Rogue: Inside the Mind of a Feminist.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Chapter 7

Rape myths

In our obsessive talk about rape and other forms of gender-based violence, several myths about rape get high circulation. We hear them in private conversations as well as in public ones. Sometimes they pass unchallenged, while at other times they are passionately defended.

Rethinking and debunking rape myths is an important part of the conversation of how to bring down the rape statistics and how to create a world without rape. Addressing them allows us to move closer to a world in which rape is taken seriously, where survivors can be supported and recover and where rape is dissuaded rather than excused.

It is also important to note that rape myths do dangerous work. They can embolden perpetrators and re-traumatise victims and survivors. Rape myths and excuses are at the heart of what is keeping rape culture intact. If we accept that it is time to render all forms of gendered violence genuinely illegitimate in all spaces we occupy, then it follows that to do so we need to stop making excuses, that we take up the challenge to constantly debunk rape myths wherever we encounter them because all gender-based violence is brutality, a form of gender war against survivors’ bodies and psyches.

The myths and excuses are listed in no particular order. I simply address them in the order in which they came to me in the book’s shortest chapter.

Perpetrators are monsters who are abusive all the time.

This is an expectation that many people have, and consequently one of the most enduring rape myths. It rears its head often when a survivor’s narrative is being questioned. Rapists and other abusers are normal people. They can be very loving and gentle to those close to them. Remember the serial rapists who were upset by the prospect of their loved ones being treated the way they treat women? That is not so unusual. There is no consensus on what characteristics are to be found in someone who is likely to rape or be abusive in any other way. The only thing that rapists have in common is the refusal to accept no.

Rape is inappropriate sex.

Rape is not sex. It is:

an act of non-consensual sexual violence, directed against a woman or someone constructed as feminine. It is an expression of masculine power and female vulnerability. Vulnerability, indeed, seems to be the theme which occurs in all the studies I have read of raped women, as Yvette Abrahams clarifies.

Rape is not about sex. It is about power. It is a highly painful experience, a highly ‘traumatic experience and like other serious traumas, it has negative effects on those who survive it. Rape is usually experienced as life-threatening and as an extreme violation of the self,’ as Desiree Hansson reminds us. One of the methods in which feminists have sought to shift the ways in which people and the legal system treat rape is through the recognition of Rape Trauma Syndrome (RTS).

The symptoms of RTS are wide-ranging and can find expression through the body, behavioural change and emotionally. Some survivors feel excessively cold, experience gynaecological problems, sore throats, tension headaches, abdominal and back pain, insomnia or excessive drowsiness, loss and increase in appetite, dramatic changes in their menstrual cycles, increased pains, nausea, discharges, sexually transmitted infections, cuts, bladder infections and other injuries on the body depending on the events of the rape. Rape survivors may change their behaviour by isolating themselves or going out more than before, may have difficulty concentrating, agitation, anxiety, depression, loss of interest in things that were important to them before the rape, oversensitivity to things that did not bother them before the rape, and may become easily startled or frightened. Rape survivors can also experience sexual disruption or significant shifts in sexual behaviour. I have known women who lost all interest in sex after the rape as well as women who reported that they wanted to have sex with their partners as part of trying to return to normal and to establish that their partners still found them sexually attractive. At the same time, I have witnessed previously solid relationships disintegrate completely in the aftermath of rape. Some survivors experience flashbacks, develop phobias or turn to substances that allow them to escape. Others develop ‘traumaphobias’, phobias both temporary and longer term that are triggered by rape trauma which may not have existed prior to being raped.

Although different combinations of these are experienced, feelings of shame, guilt and self-blame are very common. Those who seem to continue as though unaffected are in denial, in a state of shock or trying to block out the rape. Surviving means learning to confront at your own pace, and to live with the rape having happened. Counselling also helps the survivor move through the various stages of trauma to healing.

There is a proper way to respond to being raped.

This myth brings to mind a cartoon by Voices Rising that used to appear in many feminist publications until about a decade ago. It is a myth that places undue burdens on rape survivors, and this is what the cartoon captures so well. It has a policeman and a man dressed in legal garb with wig, bow blouse and black robe standing alongside each other facing forward with speech bubbles above their heads. The police officer’s speech bubble says ‘If you want to survive a rape, don’t fight back’. The lawyer’s bubble says ‘If you don’t fight back, you must have wanted it.’

There is no one way to respond to rape, nor is the criminal justice system consistent in what it expects from survivors and those who seek to support them. Instead, globally when it comes to rape, survivors often confront mixed messages.

Navi Pillay notes that the legal justice system still treats women who report rape and other forms of violation in ways that are shaped by the myths that suggest that women’s ‘sexual proclivities’ are responsible for their violation, that women are perpetually sex objects and men are both disarmed and helpless against their natural desires for women’s bodies, that women who have had sex before somehow cause the rape and also ‘that victims resist and suffer physical injury to prove that they had not consented. This ignores what psychologists and women tell us, that a non-consenting woman may well freeze, or co-operate out of fear of injury.’

Rape is when a man rapes a woman using his penis to forcibly penetrate her vagina.

Rape is a violation that can be inflicted on anyone. And the use of non-biological weapons is not unheard of. As Rape Crisis Cape Town notes:

[i]t is important to realise that rape can happen between same-sex partners and that thinking that rape can only happen between a man and a woman is also a myth. In certain instances women have been known to rape men but at Rape Crisis we have found this to be the exception rather than the rule and so we base our comments on rape between a man and a woman realising that each rape is unique even as we generalise about it.

Rape myths are just harmless ignorance.

They actually have real effects. Sometimes they have implications for who is held accountable/responsible. They create the image and an idea of ‘real’ rape and notion of mostly false rape as abundant. This is inaccurate since rapes differ and false reports are generally the exception. Rape myths enable rape culture to thrive, sometimes enable the secondary victimisation of survivors and create the female fear factory. Some rape myths shame the survivor instead of offering support towards healing.

Real rape victims/survivors lay charges with the police because they have nothing to lose.

Often when a woman breaks her silence on rape, or when several women accuse the same man of sexual assault, various people who are not directly involved insist that those ‘real rape victims’ seek out police help since they have nothing to hide.

This is possibly one of the most dangerous rape myths anywhere. Research findings on rape reporting show that only a small percentage of those who are sexually violated report the crime to the police for a range of reasons from stigma, to fear of secondary victimisation, to knowledge of how low the chances of a successful prosecution are.

A 2005 Medical Research Council report showed that only one in nine women reported their rape to the police, whereas South African Police Service 2010/2011 reported that of the 66 000 cases of sexual assault reported to them between April 2010 and March 2011, half were perpetrated against children.

In ‘The War at Home’, a 2011 joint research report by the Medical Research Report and Gender Links stated that roughly one in every twenty-five rapes are reported to the police in Gauteng. The authors predicted that there were fluctuations in this number in other provinces, with even lower rates of reporting in some provinces based on previous research findings.

Many forms of rape and sexual assault are normalised, or, to quote from One in Nine Campaign’s publication 2012 ‘We were never meant to survive: violence in the lives of HIV+ women’:

[s]ome forms of sexual violence, too, are socially constructed as acceptable because of the nature of the relationship within which they occur. Thus, a distinction is often made between ‘rape’ and coercion to have sex, with the latter comprising the vast majority of sexual violence – those not involving ‘overt’ violence and where the perpetrators are members of the family or boyfriends and husbands.

There are various reasons why rape reporting is lower than the incidents of rape. Rape Crisis counts among these reasons various consequences that may result from being identified as a survivor, including but not limited to loss of financial support if the rapist is a family member, stigma, protecting loved ones from the consequences of the rapist being arrested, lack of access to required services whether police stations are far or some other impediment, fear of further violence by the rapist and those associated with him, not being believed, and the knowledge that the legal justice system has very few successful cases of prosecution, with Rape Crisis reporting 4% conviction rates in Gauteng and 7% in the Western Cape:

In 2010/2011 Rape Crisis saw over 2 700 rape cases for direct support and the number increased to over 5 000 in 2011/2012. Some of these survivors had reported the matter and some had not. Those who had reported, experienced the justice system in many instances as helpful, with distinct pockets of excellence where dedicated officials went the extra mile on their behalf and made them believe that their case was being taken very seriously. But even when this was the case in one area of the CJS [Criminal Justice System], the opposite was usually true in another, with the result that there was no one case where all parts of the system – police services, health facilities and courts – worked well and in a coordinated fashion to ensure a successful conviction.

Rape is about male arousal and the need to have sex.

Rape is sometimes enacted with objects other than the penis, yet:

[v]iolence against women is seen as an individual male aberration rather than a social problem. The social reality for women is that they face the potential threat of violence and rape in their lives. The life of men is comparatively secure – they can walk in parks or commune at night without this fear,’ as Navi Pillay reminds us.

Dressing a certain way or being visibly drunk invites rape.

Women are raped in all manner of dress and undress, and often by people they know. There is no correlation between how a woman dresses and her ability to escape rape. Rape is about power not seduction, and men are not helpless children but adults with the power to self-control. Women should be free to dress as they please without being blamed for what might be done to them.

Rapists are strangers who abduct women in public and rape them in unknown places.

This one is not quite a myth. While globally most survivors know their rapists, there are also cultures of women being abducted from public places and being raped, either by a single man or gang raped. There are also established histories of women attacked under conditions of war. Various chapters in this book revisit this notion that women are not likely to be raped by a stranger to show that in South Africa many rapes have fallen into just this category from slave rape to colonial rape to jackrolling.

Sex workers cannot be raped.

Anybody can be raped. Just because people work in an industry where sex is for sale does not mean they are available for sex with all people all the time. Sex workers are capable of saying no, of not wanting to have sex, and therefore they can be raped. This is especially so since rape is not about sex but about power and vulnerability. Sex workers can be particularly vulnerable since they work in a criminalised sector and therefore cannot claim the same resources that other workers can.

There is also a wealth of research that shows that a significant percentage of sex workers become prostitutes through trafficking and rape. In other words, not only can they be raped, but sometimes their entry into this work is through sexual violence which may continue.

Women are accidentally raped because they play hard-to-get.

Playing hard-to-get is a patriarchal construct that enables rape culture. For as long as it is taken for granted that women are playing hard-to-get when they turn down men’s heterosexual advances, they can be pursued in a courtship process/process of the heterosexual chase that ultimately changes the refusal into acquiescence. The phenomenon of being ‘friend-zoned’ is allied to this. It suggests that there is something humorously amiss when a woman chooses to be friends with a man who desires a sexual/romantic relationship with her. The ‘friend-zone’ is mythologised in global popular culture as a form of punishment from which heterosexual men are constantly trying to escape in order to successfully attain romantic-partner status. Yet, if women are adults, indeed human beings of any age, then they are capable of saying yes when they so desire. Even if a woman is ‘playing hard-to-get’, violating her cannot be an accident.

Rape looks a certain way. It leaves a specific imprint on the body.

Jane Bennett continues to ask:

what kind of ‘physical,’ referential pain is inflicted by rape? A body is as visibly ‘whole’ after rape as before. There are likely to be abrasions, bruises – perhaps worse if a ‘weapon’ was used – but these markings are mere witnesses to the presence; they only hint at the ‘wound’ itself in a script that lends itself as easily to the description of an unfortunate accident as to the (sometimes) temporary annihilation of the semiotic process through which a woman may make sense of herself.

There are others.

It is time to stop these acts of war against women’s psyches and bodies. It is time to stop giving airplay to the excuses that make rape and all other forms of gender-based violence seem harmless, excuses that allow it to stay normal. Excuses keep gender-based violence: violence against women, girls, boys, gender non-conforming people, queers of all hues in place. They hold the survivors hostage while letting the perpetrators off.

In other words, when we make excuses on rape, we provide cover for brutal men to violate all others with impunity. Slut-shaming, rape-culture, intimate femicide, sexual harassment, sexual trafficking, the forced marriage of girls to men old enough to be their (grand)fathers, all rely on excuses to make them seem acceptable, and to make rape seem harmless.

Excuses say it is fine to punish a survivor for the short skirt she wears, fine to excuse the male professor who sexually harasses his students and colleagues, overly sexualising them, making inappropriate comments that the woman student is obliged to think of as compliments to stay alive. It is not fine.

Excuses say violence against Black women is part of generalised violence against Black people and that brutal men cannot be called the monsters they are when they rape, beat their partners and make excuses. This is another really dangerous excuse. All men, no matter what race, class or religion have patriarchal power and can choose to brutalise and get away with it.

Excuses say that only working-class Black men rape and that white women and gender non-conforming people do not have to deal with this from white middle- and upper-class educated men. Chapter 2 and 6 have many examples of white men who rape as individuals and as part of armies. I’ve also given many examples of men who are not poor who have been accused or convicted of rape.Excuses make violence against women possible – they are part of the complicated network that says women are not human, so our pain is generalised, unimportant, so we give violent men permission to keep all those they deem vulnerable, such as women, men, and gender non-conforming people or children.

When we make excuses we become the perpetrators and their allies. It is important to redefine what justice means, recognising that it lies not in political speeches, the mention of non-sexism at the bottom of stationery, for many women it is not in the criminal justice system.

Survivors of gender-based violence are the world’s majority; they walk the streets all day everywhere, sit next to you in class, they are the person you are busy falling in love with, they are your sister, your best friend, lover, mother, daughter, your teacher.

~~~

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media MFBooks Joburg Pumla Dineo Gqola Rape Rape: A South African Nightmare