A remarkable 10-year-old – Read an excerpt from The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan

More about the book!

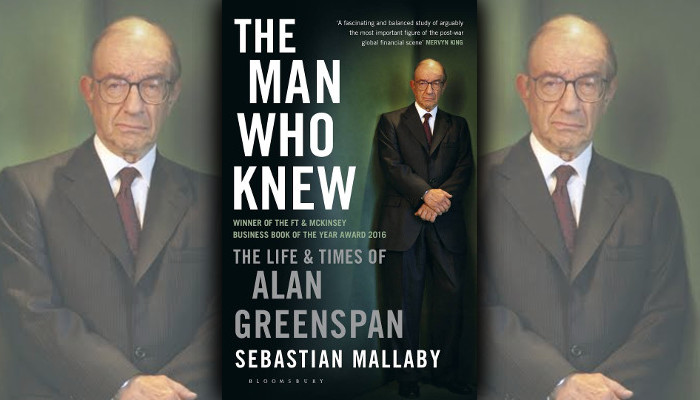

Superbly researched and enormously gripping, The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan by Sebastian Mallaby is out now from Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Born in 1926, Alan Greenspan was raised in Manhattan by a single mother and immigrant grandparents during the Great Depression, but by quiet force of intellect, rose to become a global financial ‘maestro’.

Both data-hound and eligible society bachelor, Greenspan was a man of contradictions.

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt:

Alan lived with his grandparents Nathan and Anna Goldsmith and with his doting mother, Rose. They shared a one-bedroom apartment at 600 West 163rd Street; Nathan and Anna had the bedroom, while Alan and Rose slept in what had been built as the dining room. It was a modest accommodation for four people, but it seemed a reasonable lot – better than the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side, where other immigrants lived, and not bad given that the country was in the grip of the Depression. The Goldsmiths lived on the west side of Broadway, the dividing line that separated the salubrious part of the neighborhood from the rough-and-tumble east. “The … gentility of the neighborhood … along with the style of the buildings, the parks nearby, and the cool breeze from the Hudson in the evening carried vague reminders of the bourgeois sections of German cities,” a contemporary wrote. German immigrants flocked to Washington Heights in such numbers that the area was sometimes known as Frankfurt on the Hudson.

To Nathan and Anna, born in Russia, driven to migrate to Hungary and then from Hungary to America, life in New York must have seemed a blessing almost divine – they had boarded their grandson’s imaginary train, and after much adventure had arrived safely. As for Rose, born in Hungary though now as American as baseball, there was much to celebrate, too. She had a steady job as a salesperson at the Ludwig-Baumann furniture store in the Bronx, which paid enough to meet the rent of $48 each month, keep food on the table, and even spare Alan a quarter a week for pocket money. Besides, she was happy to be living just half a block away from her sister, the well-to-do Mary. In summer Alan would stay with Mary at her vacation house close to Rockaway Beach, on the near end of Long Island. Alan and his cousin Wesley would spend hours walking the sands with their heads down, searching doggedly for lost coins. Then they would spend the fruits of their labor on candy.

Rose’s greatest blessing was young Alan himself, born on March 6, 1926, the product of her brief marriage to Herbert Greenspan. The boy naturally expanded to fill the gaps in Rose’s life – the husband who had left when their son was still small, the absence of other children. Each morning her young hero with his perfectly even features and broad smile would soldier off to the P.S. 169 elementary school on Audubon Avenue, and each afternoon he would return with extraordinary things. From very early on, he could add large numbers in his head, and seemed even to enjoy it. Rose trotted him out in front of aunts and uncles to perform. “Alan, what’s thirty-five plus ninety-two?” she would ask. “A hundred and twenty-seven,” came back the answer.

A few years after he turned addition into a performance art, Alan developed a passion for baseball, and it was hard to say what thrilled him more: the excitement of listening to the radio commentary of the 1936 World Series or the discovery of a world that could be reduced to the statistics and symbols of a prodigious ten-year-old’s devising. The statistics were straightforward, but pleasing all the same: a player who got a hit on three out of eleven appearances had a batting average of .273; one who succeeded five out of thirteen times had an average of .385; it was thanks to baseball that Alan memorized the conversion tables for fractions into decimals. But the symbols were where the creativity came in. Alan invented a notation that allowed him to track each play of the big games. If a player hit a ground ball, he would inscribe a careful x on his green scoring sheet. If the player hit a line drive, he would enter an ellipse; a circle with an x through it meant a high fly, and an alpha meant a deep hit into the outfield. Each fielder’s position was assigned a number that could be combined with the symbols to create a precise record of the play: for example, an ellipse next to an 11 meant a line drive to right center field. Reflecting on his childhood some seventy-five years later, Alan remained convinced that his system was better than anything that even the newspaper writers had invented. Rose, no doubt, had agreed with him.

Categories International Non-fiction

Tags Alan Greenspan Book excerpts Book extracts Jonathan Ball Publishers New books New releases Sebastian Mallaby The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan