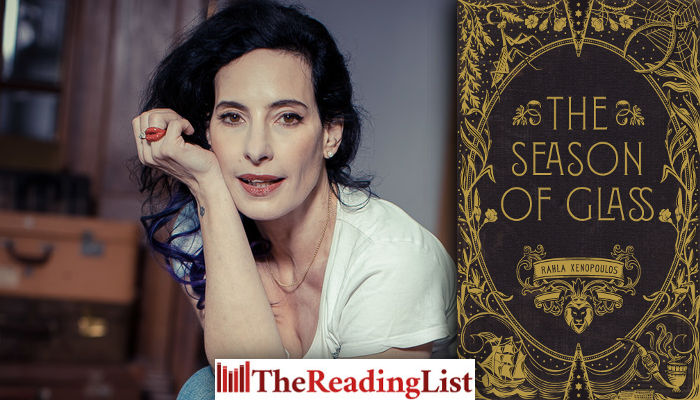

Read an excerpt from Rahla Xenopoulos’s modern Scheherazade’s tale The Season of Glass

More about the book!

The Season of Glass by Rahla Xenopoulos is a modern Scheherazade’s tale about a pair of twins who travel to pivotal moments in history.

The book takes us to a marbled city in sixteenth-century India, through dangerous Johannesburg streets in the seventies, and even to the distant future.

A shimmering novel, it is a kaleidoscope that works with light and shows us hope.

Read an excerpt from the book:

The thick belt of the white fur coat is cinched so tight, she can barely draw breath. And the weight of it is so cumbersome, she can’t move from the couch. It is her stillness the boy finds so disconcerting, so perfectly still and rigid on the green velvet chair, like a painted porcelain doll. Judith, the child who does not walk but leaps, who does not talk but sings; Judith, who floats through life, is so very still, as if she knows what is about to happen. But she can’t possibly know. Not even God could possibly know. Her childish personality cannot be contained in a coat. Its gold buttons, secured a little too tightly around her neck, are engraved with the Levi coat of arms, an ‘L’ and a roaring lion. Outside, the cold of Vienna’s winter cuts through people’s clothing into their very souls, but inside the Levi mansion a fire blazes in every room. The family are safe, protected from both the violent weather and the people outside. They exist like a moist sponge cake, shielded by a layer of marzipan and fondant icing, the Levi wealth and honour. And how he complains, Shimon, the pudgy boy: ‘Can you people not see how uncomfortable my sister is?’ She is not younger than him; smaller yes, but not younger. She is his twin. ‘Why can Judith not take off the stupid coat and come play with me?’

‘Because, Shimon, I brought this coat from Paris. The most fashionable young ladies are walking down the Champs-Élysées in this coat.’

‘Pooh, pooh, Judith is not a young lady – she is my sister who must come play.’

‘No. I tell you, Shimon, she will sit and wait in the coat.’ Rachel, my magnificent fiancée, does not raise her voice. Unlike the twins, it is not in Rachel’s nature to raise her voice. They say Rachel is her mother’s child, but I can’t say for certain since all I know of the mother is the Klimt portrait in the hallway. My Rachel is a bewitching beauty. But then they, the Levi family, are all in their way bewitching. Rachel, the twins, and even their absent father, lost as he is to his sorrow.

The gold buttons reflect the family crest proudly in the firelight. ‘L’ for Levi, the bankers and composers, the doctors and muses, the soldiers and financiers. There have been no Levi rabbis. Judaism is considered a whim, and was almost done away with generations ago in the Levi family. Yet here am I, Chaim Zechariah Cohen, the fiancé to his first-born daughter, standing at the foot of the cascading staircase, as if at home in this mansion.

Was it easy to fall in love with Rachel, you wonder? I fell in love with Rachel as one falls into a warm bath after a cold night. When she came to me, I was a wandering Jew, and her eyes were filled with the promise of a home. In all my life, I never knew of a purpose; I never felt a place of belonging until the night a friend had taken me unwillingly, out of my drab lodgings, to a recital in Montmartre. I had no interest in love or music. But that family, they transcend interest. The little girl, Judith, her voice rang through the dark Parisian night, as if her soul were illuminated. It is crude to say she sang like a nightingale. A nightingale is a bird of this earth. I can look out of my window and hear a nightingale sing, but Judith, her voice was not of this world. We never again will hear anything like her song. Not in this life. Her voice was a miracle. So young and small she was, but filled with ancient wonder.

That evening, Shimon sat at her feet, even then in a position of devotion, her twin, her protector. They were a self-contained universe, a universe of two children.

Then I saw Rachel, standing behind the two children. Who am I to describe the wonder of Rachel’s beauty? When I met her, she was the muse of Europe. Artists painted her and poets wrote verses praising her beauty, while composers swore she’d driven them crazy with longing. And she existed apparently ignorant of the disorder her magnificence created. It was not in my nature to consider women like this. I was a poor rabbi, but her beauty beguiled. It was incongruous: her neck was too long, her skin too pale, her bones protruding from her body like weapons set to cut a man’s heart to shreds. Her eyes were as black as her hair, and they pierced constantly in question and longing. There was no comfort to be found in Rachel’s beauty, but nothing in this life was as compelling.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Penguin Random House SA Rahla Xenopoulos The Season of Glass