‘It was during one of the Kalahari’s raging February storms that Kytie Rooi committed a murder’ – Read an extract from Homeland by Karin Brynard

More about the book!

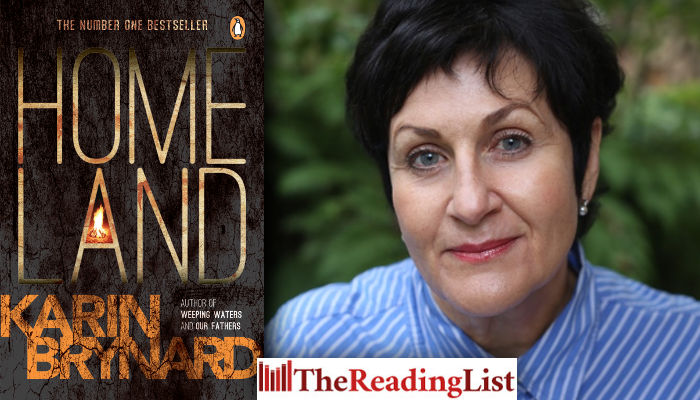

Read an extract from Homeland, the long-awaited translation of the number one bestseller Tuisland, Karin Brynard’s critically acclaimed and most ambitious novel to date!

Brynard is a journalist who earned her stripes in the burning streets of Soweto during the Freedom Struggle of the eighties. As a political correspondent for a nationwide newspaper, she witnessed the release of Nelson Mandela and the subsequent political settlement that ended apartheid. Her first two novels, Plaasmoord and Onse vaders, took the South African market by storm, becoming instant bestsellers. She has won numerous literary awards, including the UJ Debut Prize for Creative Writing and two M-Net Awards.

About the book

Captain Albertus Beeslaar has had enough of the Kalahari. He is about to hand in his resignation, but before doing so he is sent into the heart of an ancient San community: an elder has died after being released from police custody and the San blame the police. The small town of Witdraai borders on the world-famous Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, where the last of the Kalahari San eke out a living. A violent attack on a German tourist has unsettled the whole town – a case that is rubbing up Beeslaar’s new colleague, Colonel Koekoes Mentoor, the wrong way. She wants to turn her back on Witdraai and the bad memories the place holds for her.

As the heat rises, all hell breaks loose: a policeman is murdered; deep-seated corruption is threatening a major land-restitution plan for the San; and a mysterious killer is prowling the red dunes. Amid all the controversy, Kytie Rooi, a cleaner at a luxury guesthouse in Upington and self-appointed protector of a strange street child, is fleeing into the deadly heat of the desert with her charge. In this world, places of safety are dangerously elusive.

Read an excerpt from Homeland

It was during one of the Kalahari’s raging February storms that Kytie Rooi committed a murder. It happened so fast, so silently, that at first her mind didn’t register: the man making a single, surprised sound. He slid limply from his chair to the floor, landing on his knees and face. For a moment he seemed to be kneeling in prayer.

Then he sagged sideways and slowly rolled onto his side.

His eyes were still open, staring in disbelief. Then the eyelids fluttered and closed. But the surprised frown remained.

She herself was surprised. Especially at the long sigh that left the man’s body. His lips moving slightly, as if he still wanted to say something.

The last breath of a human being, she thought in amazement. The departure of the soul. Was this where God came to collect it? Or did it leave by itself, fly away into the open air, where it was snatched by the wind and scattered abroad? Never to find its way back to this person and this body. Never. However hard the rain might hammer it back to the earth.

It was the only sound she was aware of. This extinguishing of a breath. That and the ringing in her ears. A ringing and a sigh.

Until the child spoke.

‘Deh,’ was all he said.

She looked at him.

He had a big head, too big for the small body. Close-shaven, with scars on his face and ear. Old scars, from something like a cane or a stick.

She’d seen him before, she realised with surprise. Among the vagrants who hung around next to the bridge, at the taxi stop. Rough, violent, wild people. Always drunk. Matted hair, tattered clothes, faces stained purple by cheap booze. This child was with them. But now he’s here … Good Lord, what was he doing here?

He smelt of soap, his body wrapped in a wet towel. A guesthouse towel, too – snowwhite, with the name in curly lettering: Fluisterrivier.

Kytie looked at it, noticed the fine red blood spatter on the fancy embroidery. The spots seemed to quiver on the towel, hypnotising her. How white and fluffy the material was. Her handiwork. She, Kyt, she was the one who kept the washing so white, rubbed out the cum-stains and the yellow ear wax and make-up smears and other unspeakable stuff. She and her team of cleaners, here at Fluisterrivier, the grandest guesthouse in Upington, situated on the river bank. And expensive. A whole month’s pay for only one night’s stay.

And she was paid well, better than the others. And treated nicely. Plus, the overseas guests gave very good tips.

But now … now it was all over. All of it. She’d just gone and lost the best job she’d ever had.

Then the furious din of reality returned – her heart that was hammering, the drumroll of the thunder, rain pounding on the roofs.

Oh, dear God, what had she done? What, sweet Jesus? What now?

She spoke to the child. ‘He’s not dead, you hear me. He’s just lying down,’ she heard herself say firmly. ‘He wanted to be naughty. Now we must go.’

The boy’s face was narrow on his big bald head. Apart from the scars on his face, he also had ringworm.

Kytie swallowed the bile rising in her throat and tried to move, but her legs stalled.

The child didn’t look right to her. His eyes seemed glassy, the lids heavy. Too heavy. Could the man have given him something?

She became conscious of the weight in her hand. The lion. She looked at it in bewilderment. Oh Lord, it was the metal statuette from the table. How did it get into her hand?

One moment, it had still been … an ordinary Saturday. The German tour group were out for the day. Luckily. She’d finished early with the rooms, helped Nathali in the kitchen and then it was tjaila time. Putting away her cleaning stuff, she discovered the mop was missing. She must’ve left it somewhere. Room 9, perhaps. It was the last one she’d cleaned.

She’d knocked as usual, called out ‘Housekeeping!’ But the storm muffled the sound. A rattling that shook you to your bones. She’d unlocked the door, entered the room.

The man inside had heard nothing. Sitting there shirtless, his underpants down and his swollen thing sticking up, like an adder in his lap, his fingers around the child’s neck. Forcing the child’s head down, down, down.

Something terrible inside her tore loose. She’d grabbed the first thing that came to hand. Aimed for the back of his head.

Stupefied, Kytie looked at the bloodstained ornament in her hand. She let go, dropped it on the thick carpet. ‘Come!’ she said, reaching for the child’s hand.

But he jerked away from her. The towel slipped off, revealing the puny body – hollow ribs, knobbly shoulders, marks on the tummy and … only then did she notice the chubby folds between the legs.

The child was a girl!

Kytie retracted her hand. There was blood on it, she saw now. Stains on her wrists.

Dear Jesus, what had she done?

Panic.

You had no choice, Kytie, you had to. You saw what was happening here, you had to!

She got her breath back, quickly wiped down her arms – using her apron, which she’d hurriedly untied. She had to get out of here. Right now. ‘I’m not going to hurt you,’ she said as she rubbed. ‘We have to get away from this bad man, you hear me?’ The child backed away, her breathing shallow and fast, a terrified little bird.

Any moment now the child would scream, Kytie realised. She’d have to do something. Fast. She felt an uncontrollable urge to run. Just run away. Into the open veld. But the child. This whole mess of a business was because of this child!

She snatched her up. The girl screamed – a reedy sound that drowned in the noise of the storm. And she fought, wriggled to escape Kytie’s arms. ‘Stop it!’ Kytie hissed. Then the child broke free, scurried towards the corner of the room where she huddled, arms clamped over her head.

Kytie glanced around her: the big double bed, a nook with a sofa and two easy chairs, the coffee table where the lion had stood, and a sliding door leading to a balcony overlooking the river.

The man was still lying in front of his chair. No sign of breathing.

And the statuette? There!

The damn thing was heavy. She picked it up and stumbled towards the sliding door. She felt her courage fail. ‘Jesus, help me,’ she said out loud. But it was in vain, she knew. The Lord was sick and tired. Of her, in particular. Her and her nonsense. He’d left her a long time ago. She’d been on her own for a long time now.

Outside, in the direction of the main house, the swimming pool lay flat under the assault of the pelting rain. Two towels had blown into the water, floating there like drowned angels, deck chairs and umbrellas lay strewn across the lawn.

She slid open the door and the rain burst in angrily. With the lion in both arms, she crossed the wet, slippery balcony and heaved the thing over the railing, watched as it plunged into the shallow water and vanished in a haze of mud, the reeds closing up again.

Back in the room, she tried moving the man, but he was far too heavy.

Leave it, she decided. Get out of here, fast.

She searched for the child’s clothing in the bathroom, found it in the rubbish bin: filthy, stinking rags. There had to be new clothes somewhere, this would’ve been included in the fee for the girl. Unless … unless the man had never intended to return her afterwards. Good God. She fetched the child and with clumsy wet fingers she dressed her in the rags. She grabbed her hand and dragged her through the front door, ran through the rain to the storeroom. Her handbag was still there.

The storeroom was dark inside and smelt of potatoes and washing powder. This was where the washing machines and the extra food supplies were kept. Kytie pushed the door closed and leant her back against it, tried to recover her breath.

Outside, a new sound was audible above the rain – a car.

She opened the door again, just a chink.

A huge four-by-four crawled slowly past the storeroom. Its wipers working at top speed, but its lights were off. The car didn’t drive on towards reception, but stopped in front of room 9. Two men jumped out, ran to the door of the room, and disappeared inside.

What now?

Oh, dear Lord, it was tickets for her!

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Homeland Karin Brynard Penguin Random House SA Tuisland