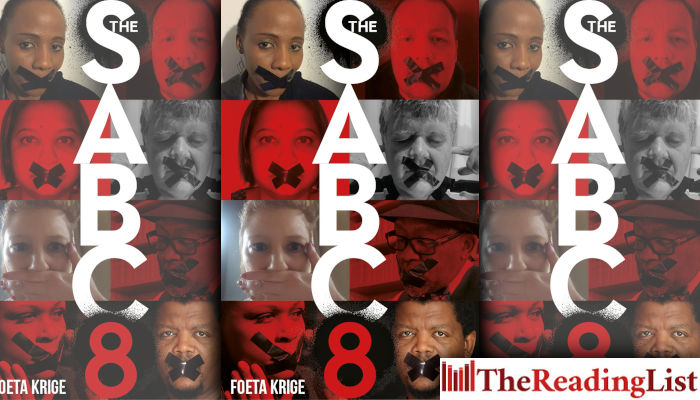

How 8 journalists stood up to censorship imposed by Hlaudi Motsoeneng – read an excerpt from The SABC8, the shocking new book by Foeta Krige

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from The SABC8 by Foeta Krige, a story of the fight for media freedom, death threats, intimidation and assault.

In 2016, the country watched as eight journalists stood up to the public broadcaster to dissent against the censorship imposed by COO Hlaudi Motsoeneng and the capture of the newsroom. They would become known as the SABC8.

While many may remember the headlines, photos and footage that circulated during that time, few know the real story: the way lives were changed while history was being made.

Now, Foeta Krige, one of the SABC8, shares his version of events: how it came about that eight very different journalists from within the public broadcaster, each with their own unique background and motivation, were brought together by circumstance to fight the mighty SABC in the name of media freedom.

This forms the backdrop for a lesser-known story – one of death threats, intimidation, assault and the eventual death of Suna Venter.

Her death shocked the nation and baffled investigators. Was it a natural death caused by stress, or were there more sinister forces involved? To understand why her death was red-flagged, it is necessary to retrace her steps and how they converged with those of the seven other journalists.

Krige takes the reader back to the day when everything started, telling the gripping, and often harrowing, story behind the sensational headlines.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

Chapter 10

The door or the window

The SABC’s decision to ban coverage of violent protests led not only to the question of how to deal with it as a journalist, but also as a media outlet reporting on its own affairs. It is a dilemma every public broadcaster must face. On the one hand it must report objectively on news events, but on the other hand, as one of 131 state-owned enterprises and the biggest communications outlet in the country, it is bound to be in the news and must therefore be held responsible in the same way as others.

As a journalist, I believed there was only one way to handle it: put the facts on the table, get all affected parties to react and then give the SABC the right to reply. In the end we should be accountable to our owners: the people of South Africa. And that’s exactly what we did. On Friday 27 May 2016 we set up a discussion for our Monday morning news actuality programme and invited Professor Franz Krüger, the head of the journalism department at the University of the Witwatersrand, and Tim du Plessis, a former editor at Media24 and member of the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF), to participate. We also invited self-appointed editor-in-chief Hlaudi Motsoeneng to speak on behalf of the SABC. Initially his office did not respond to the invitation, but we did get a message later in which he promised to come to the Monitor studio at a later stage to, in his words, ‘face the music’.

During the Monday discussion, Krüger and Du Plessis did not mince words. They both believed that management’s decision was incompatible with not only best practices, but also the SABC’s own editorial principles. It was a worrying decision so shortly before the coming election. Krüger, who was part of the broadcaster’s post-1994 news management team to transform the organisation into a true public broadcaster, believed that this was a step backwards.

The following morning, Motsoeneng arrived at our studio for an interview. He was accompanied by Anton Heunis, a retired SABC manager who did a short stint as acting CEO in 2015 before ill health forced him into retirement after forty-four years of service. It is rumoured that his pension package was the highest ever paid out to an SABC employee. He was back now, as Motsoeneng’s personal advisor, at a salary of more than R4 million per year. After the interview, the two men confronted me about the merits of the previous day’s show. In a heated confrontation I expressed my dismay over the fact that news staff had to read about the ban on social media and the general lack of communication between top management and the newsroom. Motsoeneng then summoned me, Sebolelo Ditlhakanyane and the current affairs executive producer of SAfm, Krivani Pillay, to his office on the twenty-seventh floor of the radio building.

It is a long walk from the second floor of the TV building, where our newsroom and studios are situated. From the open-plan radio newsroom, you walk through a short passage and down a flight of stairs to the ground floor, passing through a longer passage and going down the escalators before you enter a 150-metre tunnel that connects the TV building to the radio building. Upon reaching the ‘other side’, you pass the radio reception desk, swipe your security card at the turnstiles and enter the lifts, which will take you to the twenty-seventh floor, the seat of power.

There were seven other people in the boardroom. On my left, Heunis, seated next to Motsoeneng at the head of the table. On the opposite side were acting CEO Jimi Matthews, acting head of news Simon Tebele and spokesperson Kaizer Kganyago. On my side of the table were Pillay and Ditlhakanyane. I took out my notebook and pen, trying to look calm and assured.

Motsoeneng was direct and to the point. ‘We are cleaning up the organisation,’ he said. ‘People are doing their own stuff. There are many journalists outside that want to work for the SABC. The environment outside is bad. No person is independent. The SABC is independent.’ While I was making notes and wondering where this was leading, he continued, ‘This is a new SABC. You must adapt or find a job somewhere else.’ Only then did he refer to the interview of the previous day. ‘Tim du Plessis is from a rival organisation. We cannot allow people from outside to say anything negative about the SABC. You’ve asked Franz [Krüger] leading questions.’ And, as an afterthought, directing his comment to the two women in the room, ‘The Editors must go. It is advertising for rival newspapers.’

For the past twenty years, The Editors had been an established Sunday morning current affairs slot on SAfm, where senior journalists and newspaper editors discussed the top news events of the week. My station, RSG, has a similar programme on Sunday nights, where news analysts discuss both local and international news trends. Although Motsoeneng did not mention our programme Kommentaar, I experienced a feeling of discomfort. Before I could internalise it, Heunis spoke. ‘I am an RSG listener,’ he said. ‘I know I am not a journalist, but you misunderstand editorial freedom. Your anchors are asking leading questions. Why didn’t you do an insert on research that shows that presence of cameras leads to violence?’

It was difficult to keep my anger under control. ‘If you had liaised with your editors and warned us beforehand of such decisions, and maybe given us insight into the research on which the decision was based, we would have been forewarned,’ I responded. Motsoeneng chipped in then, taking the sting out of Heunis’s argument. ‘I do not believe in research!’ he exclaimed. ‘You must defend the organisation. No journalist is independent. The COO has the final responsibility for news.’ Looking at Tebele, he said, ‘Simon, if people do not adhere, get rid of them. We cannot have people who question management. This is the last time that we will have a meeting of this kind. From now on, you handle things on your level.’

Matthews, who had been quiet up until then, solemnly responded, ‘It’s cold outside. If you don’t like it, you can go. You’ve got two choices: the door or the window.’ The fact that we were on the twenty-seventh floor did not escape me. I stared at the window. I knew that the view of Johannesburg from here would be breathtaking, but this was not the time to contemplate the beauty of the city. I was embroiled in my own thoughts, the rest of the discussion just background noise.

The battle lines had been drawn.

While walking back to my office, through the reception, down the long tunnel and to the TV building, I thought about the meeting, the way forward, and specifically Matthews’ words: ‘You’ve got two choices.’ It never occurred to me that he could have been referring to himself, because less than a month later he walked out of the SABC after offering his resignation. He chose the door.

By the time I reached my office, I knew Matthews was wrong. There were not only two options. There was a third: to fight back. How, I did not know then, but when I sat down at my desk, I took out my notebook and started typing up my cryptic notes of the meeting.

~~~

Categories Non-fiction South Africa South African Current Affairs

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Foeta Krige Penguin Random House SA The SABC8