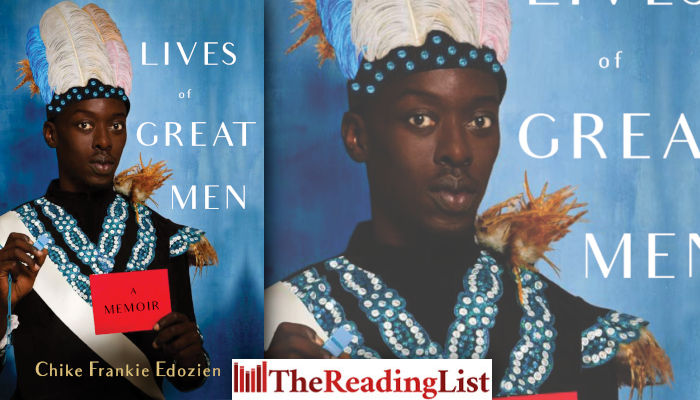

‘Get married. Have babies. Then continue with secret boyfriends.’ Read an excerpt from Lives of Great Men by Chike Frankie Edozien

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Lives of Great Men, the award-winning memoir from Nigerian journalist Chike Frankie Edozien.

From Victoria Island, Lagos to Brooklyn, USA to Accra, Ghana to Paris, France; from across the Diaspora to the heart of the African continent, Edozien offers a highly personal series of contemporary snapshots of same-gender-loving Africans, unsung Great Men living their lives and finding joy in the face of great adversity.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

Prelude

Forgetting Lamido

‘Until the lion has his historian, the hunter will always be a hero.’

– Anonymous (Elmina Castle, Ghana)

I open my eyes but I’m not moving. This siesta has probably lasted twenty minutes and now I’m staring at the lanky, striking man awakening beside me. It’s mid-afternoon, and outside the streets are choked with crawling vehicles. Over the past few days the ubiquitous horn-blaring has been getting on my nerves. When did Ikoyi become so noisy? At least it’s serene here inside the Moorhouse. The air conditioner is humming softly, chilling the room. The severe brown wood panelling décor is masculine. Nothing’s soft about the furnishings. This small boutique hotel may be tailored for busy businesspeople but it’s also an oasis amidst the chaos of Lagos. And it’s in this oasis that I’m reconnecting with my childhood love. I stretch and see our naked selves in the mirror, legs intertwined on crisp white sheets. All afternoon we’ve been canoodling. Then having furtive, furious sex.

It’s been ten years plus since we last met. Even after all this time our bodies haven’t lost that feral magnetism for each other. At first we tried to tamp down the sexual tension by staying out with others at the bustling Eko Hotel. But in the end we just gave in.

He stirs, spurring me to inch closer, put my arms around his waist and peer over his shoulder. He smiles and I melt.

‘You dey okay?’ he asks softly.

Years ago, whenever we were alone, his deep voice softening to a whisper made me feel loved, and it does today. He still has dimples and the whites of his eyes still shine against his groundnut-coloured skin. He has no tribal marks but turns to look and see if mine remains. Few people notice it. It is tiny and hidden like a small scar under my right eye. He finds it, smiles and strokes it with his thumb. Then he kicks off the sheet. And as my Fulani lover’s sinewy, naked body stretches out into the ‘X’ position I touch his ‘fro gently, marvelling at how thick and soft it still is. What sort of pomade is he using now? I gaze at this body that’s remained taut, even though it’s now without the chisel of yesteryear.

‘You look great,’ I say, gently fingering his bellybutton. His stomach tenses.

‘I no be fine boy again oh,’ he replies, adding, ‘Your hair still plenty.’ He always appreciated the hair that sprouts abundantly all over me. I shave my head and face but I love my hairy chest, legs and arms, and rarely trim or ‘manscape’. I’m happy it still thrills him but I feel trapped. Even his scent, a mix of cigarette smoke and musky cologne, holds me captive. I hug him tighter. That Diana Ross ditty floats in and out of my consciousness: ‘Touch me in the morning/Then just walk away/We don’t have tomorrow/But we had yesterday …’.

What am I doing? I’ve just spent hours having sex with someone else’s husband. And now we’re in a post-coital afterglow with little to say. I remember him always talking, even after sex, but today he just smiles. We look into each other’s eyes. We both want to be here. Guilt isn’t part of the equation. With this man it never has been. Not when I was nineteen, and not now, when we are both in our thirties. Nothing’s changed. Yet somehow today everything is different.

Alhaji Lamido Gida and I first meet in the 1980s, when we and our families lived not far from this hotel. My brothers and I are Ikoyi boys, ‘Aje butter’ children – middle-class kids whose parents have multiple cars, homes with domestic help and who send them abroad on holiday. Lamido is twenty and to my mind an adult. He’s friends with my elder brothers and we meet when he comes to visit them. I’m sixteen and home on holiday from boarding school in Port Harcourt.

During my years at the co-ed Federal Government College I’m introverted, bordering on shy, but come alive when I get involved with the drama troupe and the press club. It takes three years before I finally begin to enjoy boarding, and by the time I meet Lamido I have friends from all over, not just the Lagos kids.

I also discover that the boys’ dormitory, where these lifelong friendships are formed, and where everyone strategises about chasing girls, is home to hidden but rampant guy-on-guy desire.

By sheer happenstance I’m seduced by a classmate who I call Smiley. Although he’s two years older than me, we’re both going into Form Five and gearing up for the West African School Certificate examinations.

After oversleeping one morning I didn’t have a pail of water to bathe with. I’d already missed the bread-and-boiled-egg breakfast and didn’t want to risk wasting more time with the trek to the outdoor quadrangle where the twenty-four communal taps were situated. So I ask Smiley, who isn’t one of my friends but who is also running late, if he can share his full bucket with me. I expect a ‘no’ but he says yes with a little smile. And we bathe together, sharing the water, scooping just a little at a time so there is some left for the other. I make it to class on time and we become pals.

One evening when I go to fetch him for night study I’m surprised to find he’s not ready. He has a brown cotton wrapper tied around his waist and no shirt on, as if he’s about to go to bed. Without a word he pulls me into one of the tiny inner rooms behind the long, bunk-bed-filled main dorm, locks the door quickly, turns out the lights and whispers, ‘Shhh.’

We keep still while the prefects usher everyone else out. I hear the clanging of the chains on the outer gates and know everyone’s gone. Smiley sits back on the lower bunk and beckons. The tiny room has only space for one bunk. I lie beside him on the thin foam, and in the darkness he begins giving me little pecks on my lips and then my cheeks, sending sensations I’d never had before shivering down to my toes and up along my spine. I’m contorting each time he licks someplace. Then the furious rubbing of his prick against mine through the fabric of my shorts and his wrapper gives way to us removing our clothes. Smiley whispers, ‘Turn this way.’ I’m confused but he gently moves us into a comfortable position. And for the first time I’m having sex. Intercourse feels weird at first, then fantastic. There is pain, but that comes later. When in the deep throes of ecstasy I heave and ejaculate I think I’ve just peed. Smiley calmly explains, ‘It’s just sperm.’

That night kicks off moments with him that I can’t even tell Paulie, my best friend back in Lagos, about. At fifteen this kind of sexual play is new to me. But not to Smiley, who tells me of others he’s ‘gone out’ with. Boys having sex with each other surprises me. Until then I didn’t realise it was even possible. After I leave I feel great, but later the ‘good boy’ in me is wracked with guilt. The term is almost over, thankfully, and the first thing I do when I arrive home in Lagos is head to my parish and get on my knees in the wooden pew, where my priest gives me his undivided attention. During these years confession was often heard out on the church verandah, privately but not in a wooden box.

‘Bless me father for I have sinned. Since my last confession …’ I have lost my innocence.

The Church of the Assumption in Ikoyi is a single-storey building next to a marble office tower and across from the Falomo Shopping Centre. I’m a regular reader at morning mass and have worshipped here with my family from infancy. The young priest knows me well and names my ‘sin’ homosexuality. He acknowledges my internal struggle and encourages me to end this liaison. He is sympathetic but warns of consequences and makes me feel that this is behaviour I can vanquish if I just try harder. And am strong.

But I’m never strong when I return to Port Harcourt. No number of Hail Marys work. At some point I move into Smiley’s room. We’re now seniors prepping for O Levels so I’m not under scrutiny as I was when in the lower classes. Another classmate – Christopher – and I also begin to fondle occasionally, sneaking off when we can, meeting by the twenty-four taps under cover of darkness for moments of frottage. But I know this thing is passing: it’s puberty play, purely physical and devoid of real emotion. So I keep going to confession and I pray. I pray for a good girlfriend. I pray to be like my four elder brothers.

Lamido changes all this. I’m now in Lower Six and have more freedom at home. I’ve aced my O Levels but flunk the yearly Joint Admissions & Matriculation Board (JAMB) exam so can’t get into university yet. My options are either to take it again a year later, or complete my A Levels, which will take a further two years of study. As I prepare to retake the JAMB I’m studying all day and partying with friends at night.

On Friday evenings Paulie and I usually head to Jazz 38 on Awolowo Road to listen to live music. Sometimes the Afrobeat King, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, pops in en route to Ikeja, where he plays his standard set at the Shrine.

Paulie and I have been close since primary school, where both of us eschewed football and worshipped Motown divas, particularly Diana Ross. We were blissfully peculiar before we knew what it meant to be so. Taking turns at the microphone on the outdoor stage to belt out Sade Adu’s ‘Smooth Operator’ is becoming our thing.

Lamido appears in the crowd, sees me, waves and comes over to us. Though his parents are in Kano, he lives with his siblings in Ikoyi. He’s up for anything in the name of fun. He feels no guilt. ‘I’m a Muslim,’ he tells me, ‘so I don’t drink, but I’ll smoke anything smokable.’ I nod admiringly. He oozes charisma. He loves his brothers, reveres his sister and dotes on his nephews. It seems his siblings are in charge of his education. There have never been sparks between us – he’s really my brothers’ pal not mine – but now, as my friends and I gallivant around Lagos, I start running into him often.

Strolling by the waterside near the 1004 residential complex on Victoria Island to gawk at folk, gist and drink is something Paulie and I do often. In those heady days after high school, seeking out palm wine or barbequed meat has become de rigueur for us. We generally stroll along the lagoon on the road to Maroko, but sometimes we make a detour and stop at the chop bars on Bar Beach, along the ocean side of the island. Victoria Island is upscale residential, and more and more nice joints are popping up all the time. We both love to people watch.

Other times we retreat to the snooker room at Ikoyi Club, the members-only recreational enclave that has been there ever since it was founded in 1938. Our friends bring their girls along. We all go to the same house parties. Sometimes I have a girl who likes me and I invite her to tag along; at other times I’m solo. I’m fine alone.

It’s on one of these unattached nights out that I run into Lamido near 1004. He and I leave the others and go get suya near the Second Gate. I find these piping hot skewers of beef, peppers and onions irresistible. It’s a cool evening and Lamido’s wearing one of his floor-length caftans, a brown one, with black leather slippers. Chatting with him alone while chopping suya and licking our fingers feels nice. Afterwards he takes me home in a taxi. We get out at the Queens Drive junction and stroll to my gate. Once under the giant tree that provides shade during the day and blocks out the streetlights at night, he leans in and sneaks a kiss. His tongue slides in and out of my mouth very quickly. No one can see. It’s unexpected but so enjoyable all I can do is smile. I’m seventeen; he’s twenty-one. Before tonight I’d not thought of him romantically. He smiles and says he’ll see me tomorrow, and many subsequent evenings he comes to fetch me, for us to hang out alone. ‘Oya make we waka commot,’ he says before our moonlight strolls. He’s old enough to drive but I’ve never seen him behind the wheel: we take taxis everywhere. When guys walk hand-in-hand it usually feels brotherly, but I get goosebumps every time he touches my hand. I shudder when his hand meets the small of my back. He’s tactile and I like it.

Lamido’s a man-about-town, energetic, slim, with a thick head of soft black hair. I love touching his ‘fro. I like his dimples. He’s always elegant, and his scent – cigarettes and cologne – makes him seem so adult. His body is toned but I’ve never known him to play basketball, football or any other sport. He talks a lot, switching effortlessly from Hausa to pidgin when sitting barefoot on the floor with the house-helps; but at Ikoyi Club he’ll discuss politics in the Queen’s English before going dancing.

He’s a tough guy, but when we’re alone I see only tenderness. He tells me jokes in a soft voice and is, he says, full of gratitude for me. I love that his eyes light up when we meet. He loves that I’m not so butch, and doesn’t mind my sometimes swishy gait. Gossip has little effect on him. He lives contentedly in his own space and I enjoy being there with him. He only desires that we meet. Often. In the bedroom reserved for overnight guests in my family’s home we’re constantly having life conversations, then having sex when everyone’s at work, then more conversation, followed by more lovemaking. We talk of our dreams too. Lamido encourages me to dress traditionally and gifts me a metallic-grey brocade caftan. It has intricate embroidery in thick white thread around the chest area and along the edges of the sleeves and hem, and is obviously expensive. He thinks I can pull it off with the kind of natural savoir-faire that he has as a Fulani man, but all I want to wear are jeans and T-shirts from London. He seldom wears Western clothes, but when he does his outfits are more fashionable than anything I own. He’s the first to use the ‘L’ word. ‘You’re my first love,’ he says over and over.

I stop going to confession.

But sometimes I wonder: is he just ‘toasting’ me, as we guys do? I’m not sure how this love happened. Lamido is popular and has options, including the many girls who want him. Meanwhile I’ve been going through the motions with a Warri girl who has decided that I’m her boyfriend, now that my brother is done with her. I say okay: it seems the easiest thing to do. Back in Port Harcourt I had a girlfriend. Most of the time we just passed notes and met up to chat. It was fun and simple, but not electric. Now in Lagos I have this girl who, after flirting with my brother, has settled on me. And it’s fun to take her places, to hug and hold her tight as we say goodbye; to show her off. But the truth is, I have zero desire for her. When Lamido looks my way, my heart beats faster and my smile grows bigger. It’s a jolt and I’m happy.

I find Lamido has a whole circle of friends who are similar to himself – top and bottom, or ‘TB’ guys, in-house slang for the peculiar. He’s far along in his studies at the Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria and has a girlfriend there. I’ve seen her picture. He rarely mentions her to me, but often shows her photo to others.

After one term in Lower Six I abandon school and focus solely on studying for JAMB. My brothers are already at university so I’m the only one at home. On my second try I pass, and later receive my admission to the University of Port Harcourt’s theatre arts department. I’m supposed to be thrilled, and in a way I am, but it means saying goodbye to my love. When we meet up, we talk about how we could disappear and get hitched … if not for the gender thing. ‘If to say you be girl, I for don marry you carry you go Sokoto,’ he says.

In my first year at ‘Uniport’ I’m a young man in love. But not with Janice, the girl I’m now dating, (the Warri girl moved on when I left Lagos). I’m acting and even get a part in the lavish operatic dance-drama production ‘Woyengi’ at The Crab theatre. It’s demanding and I give myself over to it, but still I yearn for Lamido. I wish he could see the show. I long for his touch, his constant whispering in my ears, telling me that I’m his bobo. I miss the way he pulls me close, his reassurances that all will be well. I ache for him.

I crave Lamido even when my high school romp-mate Christopher appears on the scene. We bump into each other on campus, and every so often he politely asks to visit – dormitory space at Uniport is so tight I’ve had to rent a room in Choba village. It’s in a bungalow that is home to a large polygamous family and my room is next to the shared toilet. It’s tiny, with just enough space for a single bed, an ironing/study table and chair; and there’s a corner in which to hang clothes. The paint on the walls is blue and peeling.

Though I miss the camaraderie of dorm living, in Choba I have some degree of privacy, and my space is also a refuge for Christopher. He’s discreet, visiting only late at night, and when he stays over, slipping out very early, before the family rises. Once we’re in bed, we pick up on the frottage we engaged in during our last year of boarding school. Afterwards we say little, and we never socialise together; we hang out with our girlfriends and exchange nothing more than a quick hello if we run into each other. These encounters make me hunger for Lamido’s full-throttle, passionate lovemaking and big personality. Christopher’s fun but unsure, while Lamido’s certain and knows how to fuck. And live. Now, more than a decade later, Lamido and I are luxuriating on the king-size bed at my hotel. I’ve rediscovered his touch and realise how much I’ve missed it. But he’s been some woman’s husband now for more than ten years. He’s also a businessman, running an import concern in one of the new office towers near Kingsway Road.

The next evening he brings along a strapping gardener from Suru-Lere who he’d introduced me to the day before as ‘someone to play with later’. The guy’s handsome, quiet, noticeable even when he’s saying little. His arms are huge, and his body’s carved by the work he does. I feign appreciation but yearn for the old days: then Lamido would never have thought to share me.

But now he’s declaring we must ‘chop this yam together’. We have a threesome. This is a first for me, and really what we do is take turns having furious intercourse with the gardener – which he enjoys – before turning to each other to make love tenderly.

The gardener’s a tall area boy with a shaved head and shaving bumps on his chin, and I enjoy chatting with him once our roll in the hay is over. His voice is soothing and I find I like him. His mother is Yoruba, from Lagos, and his father is also Yoruba but from Benin Republic. Lamido isn’t his boyfriend but they have a ‘special friendship’. Over cold Star beers I gather that he earns little and has a wife and young son. He helps Lamido out sexually and Lamido helps him out financially.

When he goes to the toilet Lamido derides him as an ‘ashawo’. I laugh, but I know he’s no prostitute: he’s just told me with pride of the flowers he’s planted nearby and other gardening jobs he’s done lately; he just hasn’t earned enough to make ends meet. I give little thought to the seediness or morality of their arrangement. People use each other; that’s life. I notice the genuine affection he has for Lamido, but in my gut I know Lamido won’t ever reciprocate. Love isn’t in the air for either of us. It’s clear that Lamido can’t stay away from me physically – he’s still caressing my tribal mark and rubbing my chest hair – but he has zero interest in rekindling the relationship. The gardener can’t see it yet, but Lamido is moving on from him too. We can all play here a while, then everyone has to return to their lives, their women.

I wondered how Lamido could move on so easily after seeing me. But after all it was me who chose to leave, even though leaving him behind was difficult for me.

After my first year at Uniport, things changed. The labour strikes and student unrest were constant. And home was a powder keg.

Things began to deteriorate when my two immediate elder brothers secretly left the country and emigrated to America. Then Mum left. At nineteen I was so angry my mother had left that I lost my fear of talking back to my father. I no longer put him on a pedestal. In many countries there is the expectation that when a marriage crumbles the children must be maintained at the standard they have grown accustomed to. Not in my case. My main concern was simple: who was going to pay my school fees? The rug was pulled out from under my feet: I could no longer afford to remain in school. And Dad didn’t do anything about my expenses. I, in turn, sneered at the woman he brought home and openly scoffed at his sister’s insistence that I go to confession for being so rude. Normally obedient, I was done with that. I had an attitude and it wasn’t one of deference. And then one evening, in front of his new paramour, he told me I was no longer welcome in the home I’d grown up in. ‘You can’t stay here,’ he said as she looked on.

The thing to do would have been to fall on my knees and beg. But I just looked at them defiantly, shook my head at the usurper so desperate to become the lady of the house, then went upstairs, packed my bags and left.

I have not lived in any of my father’s homes since.

A friend of my mother’s who lived close by took me in. I returned to my studies but was constantly broke, living off the generosity of my friend Fela, who split his money with me so I could afford to return to Lagos – albeit only by bus. For years I’d taken the forty-five-minute flight; now it was a bumpy twelve-hour road trip. I was constantly brooding. I studied but, having no money, didn’t hang out. I auditioned for and got bit parts on TV shows, which was encouraging, even exciting, but the payments never came. Fela kept me sane by regularly pulling me out of my room and sharing everything with me.

My mother was furious when she found out that Dad had withdrawn his financial support and I was all but starving on campus – she had not expected him to go that far. A year earlier I’d been promised a summer holiday abroad, and my mum, despite now having to make a new life for herself, didn’t renege. She bought the ticket for me when I returned to Lagos for summer break. I was to go to my aunt’s in London as usual. We had one last meal at Ikoyi Club, and Aunty Joy, a friend of Mum’s, casually gave me several hundred British pounds for spending money.

During this difficult period Lamido, the one person who knew me inside and out, and loved me, had little time for me. He was now about to marry his girlfriend. We would not be disappearing together. He’d graduated, begun working; marriage and procreation were the next steps. He had been on pilgrimage to Mecca and was going to have a nice wedding. I, on the other hand, had nothing.

So I zapped. I left Port Harcourt. Difficult as it was, I left Lamido to his new wife and went abroad with no intention of returning.

My first stop was, as intended, London. In happier times I’d been there for summer shopping; this time I spent three months cleaning a bakery in Willesden, to earn some money before making my way to America.

America was a struggle at first, though my brothers helped me find a night-time office-cleaning job and a small room to rent that was just a ten-minute bus ride away from the community college I had enrolled in. Lamido and I had little contact and our communications withered. He showed no inclination to visit, and I was determined not to return to Nigeria until I too had a degree: I wasn’t going to be the one who dropped out. So I adjusted to a life of classes by day, twelve-hour shifts by night and sleep deprivation, but I did graduate, and I began working as a journalist. Acting was out. I was twenty-five and unburdened. For the first time I felt free to make my own decisions.

After years of struggle I lived an honest, openly peculiar but low-key gay life. No one in New York cared. My brothers made no fuss; they had gay friends by then. My sister and mother visited – at different times – the tiny apartment I made my home in Brooklyn and reoriented themselves to my reality. I never hid.

~~~

In the late 1990s, on my first trip home since I’d left in a hurry, Lamido was the one person I sought out. I began to come home more often, seeking out work in Africa. In those years many friends and classmates who had fled the country, for higher education or to escape the political turmoil, began returning. But it seemed every ‘TB’ boy who came home followed the Lamido model: Get married. Have babies. Then continue with secret boyfriends. From my childhood best friend Paulie to Smiley and many in between, everyone fell in line.

Was it the price of living hassle-free in Naija that meant all these TB guys had to find wives? Could they not just be discreet and live without having to marry women they had little interest in?

Of course, the pressure on women is even greater – at a certain stage all they hear are questions about getting hitched, as if all their accomplishments add up to naught if a husband isn’t there to be shown off – but I started to believe these men needed wives to succeed professionally. One friend said he would never have gotten that promotion to senior lecturer at the Ambrose Alli University in Ekpoma if he had remained single. ‘You’re considered mature if you are married,’ he told me. ‘That’s the way it works.’

Having found a career where my sexual orientation hadn’t been an issue, I wondered if I’d be able to work full-time in Lagos at a high level without this ersatz symbol of maturity. Folks who presented me with opportunities said yes, of course. I wasn’t sure this would have been the case if I’d remained at home, and so I empathised with friends who’d had to join the marital bandwagon.

Some insisted I was overthinking it: ‘Oh, you still spend too much time working in New York – when you move home fully you will marry and have someone on the side. That’s the way it is.’ or ‘Everyone does it.’ No one pays any attention to a man’s effeminate gait or his preference for the company of other men after he’s paid some woman’s dowry and put a ring on her finger.

My lecturer friend left Ekpoma, decamping to England to teach. He took his wife with him and his charade continued, though he couldn’t find a solid relationship to have on the side. He isn’t unique: from Manchester to Chicago I meet successful Nigerian professionals in this boat. As long as they are perceived to be heterosexual, it’s all good to them. Once when I was in London, a Delta-Ibo man with a thick beard and shaved head tried to pick me up in a pub on Rupert Street. I enjoyed the attention and found him very attractive. He reminded me of the late Igbo military leader Odumegwu Ojukwu. It was a plus that he had lived in Asaba, my hometown. As I downed my lager shandy I sized up this to my mind potential mate. We flirted all night, even exchanging kisses after last orders had been called. It was fantastic – that is, until he began to give me details of his upcoming nuptials in Lagos. I stared at him.

‘Don’t you have the same pressure?’ he asked, shocked that I found it incredible he was going home to marry. ‘She’ll be there now! I’ll do my thing, ah ah!’ he said.

Is it just the career, or is it also parents pushing for grandchildren that leads these men to marry women they aren’t in love with and don’t even desire? Sharing a life with someone you don’t love can’t be easy and I’m not sure I could do it.

I’m lucky; my parents have grandchildren already, so I’m not tasked with keeping the lineage going. My father and I, after some years had gone by, put love ahead of pride, and we now have a warm, open father-son relationship. We are proud of each other. I also have uncommon freedom because my siblings love me unconditionally. But every family is different: I know my supportive siblings aren’t the norm, and far too many men can’t risk being cut off emotionally or financially from their families. I’ve known for years that Lamido’s sisters and brothers wouldn’t accept his gayness. Not back then, and not today.

In the years following our initial reunion in Lagos, whenever I’m in Nigeria I make the effort to meet up with Lamido. He’s since settled in Kaduna. All he requests of me when I visit is to bring him some poppers from New York. As he’s aged he’s embraced his softer side – like when he tells me how he just missed being the ‘first lady’ of one of the northern states when his ex-boyfriend lost the election.

One evening while I’m in Abuja we go to his brother’s home in Asokoro for dinner. The meal is an elaborate spread of tuwo shinkafa with goat meat and fish soup. There’s no booze, but the conversation flows. I listen as his siblings talk about flying across the country in a private jet with their friends. His now grown-up nephews are preparing to head back to British universities and gab on about the different business-class options. Lamido, his current boyfriend and I have a swell time. But even in this rarefied and intimate bourgeois circle Lamido refers to his man as a friend.

When our hosts rise from the table and are out of earshot I say to Lamido that his new boyfriend is really nice. He shoots me a look of absolute panic. ‘Na wetin I do you now?’ he says. I’m not to use the ‘B’ word while in the house. I apologise profusely: I thought it obvious that they are a couple. But if he refuses to acknowledge it to his relatives, then as far as they are concerned his relationship doesn’t exist.

Back in Lagos, over some Chapmans at Bogobiri, Paulie isn’t surprised. He tells me his own fear is not just of his brothers, but his in-laws. Should they ever find out about his boyfriends, he’ll just deny it, he says.

I often wonder if Paulie and Lamido had a thing after I left. They both refer to each other as Lagos sluts and never hang out together. Now both of them are married to women they never spend any time with, pretending to the world they don’t love men. Smiley too, who never left Port Harcourt and eventually became a preacher who punctuates his sentences with ‘in Jesus’ name’, would be devastated if his family found out what really stirs his loins. He’s been ‘happily married’ for years.

One schoolfriend who it had seemed to me wouldn’t deign to marry for societal approval eventually did, and it shocked me: Chidi Omalichanwa, after decades in Europe, returned to Lagos and pulled a Lamido. He was a class ahead of me, and I had no idea of his gay adventures until we reconnected in the early 2000s. Chidi told me that back then he was sexually active with some of our schoolmates. All boys, all now married with children.

I felt the electricity that passed between him and another classmate when we all bumped into each other recently. Their hug was long and tight,a and then both seemed to get shy and be momentarily at a loss for words. They hadn’t seen each other in thirty years.

After high school Chidi got an engineering degree then went to Europe for postgraduate study. His career skyrocketed. I admired his joie de vivre, and seeing his successes I wasn’t surprised when he moved home to helm a multinational. Over the years the geek I remember morphed into a macho guy – tall, broad-shouldered, dark-skinned and handsome, chic and bespectacled, an Oga at the Top – with a good career, a good home, an upper-middle-class life: a catch. But still I was dumbfounded at how quickly he married a woman he’d met soon after resettling. Children followed.

After two decades of boyfriends Chidi is now forty-five and ‘straight’.

It made more sense to me for Paulie, who had never moved away, to get married, and I was able to rationalise Lamido’s marriage for similar reasons. But Chidi’s remains a head-scratcher. The man returned to Nigeria with accolades and his hiring was a coup. He already had the career and financial muscle so why jump into forced heterosexuality? Over the years he’s joked – or at least I thought he was joking – that I was lucky I got away from him in high school; he’d set his sights on me, he claimed, but my sexual awakening only happened later. I’d flirt back lightly and say, ‘Damn, if not for that oyinbo boy you have, we could have been together.’

Nowadays my response is a poker-faced, ‘Too bad! You’ve gotten married!’

One very clear evening, when the stars are shining brightly in the Lagos sky, Chidi and I join other school friends for drinks at a swanky V.I. hotel rooftop bar. I’m swilling wine and having a good time.

After Chidi’s downed a few shots of Maker’s Mark I pull him away for some real talk. In a low voice he tells me that even though he had male sexual contacts in school, at university he had three serious girlfriends. ‘Ah. Maybe he’s one of those truly bisexual guys,’ I think. But then, after moving to Europe, he fell in love with a man. There, though he certainly finds black men extremely attractive, he dated English and Irish lads only.

As he talks I’m reminded of a difficult break-up he’d had a few years before he returned to Lagos. Even though it was raw, I had hoped he’d get over it; I hated to see my friend, a really good guy, so hurt. But now here he is, telling me that that break-up was the straw that broke this camel’s back. Loving dudes afterwards was just too hard, he said. His solution to healing was to tell himself, ‘It’s time to settle down and get married.’

If he’d married right after he left the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, would he have missed out on his amazing career abroad? Or might he have soared all along in Nigeria, rising higher than he is now? Probably: he’s that bright. I stare into his eyes and wonder, how is he doing this?

It’s proving difficult: his attraction to black men is strong, so he’s avoiding places where he could be hit on. But yes, he has flings. ‘Each time I travel to Europe. They’re not lovers, just “contacts”. It’s not as if I’m looking, but if I travel it happens. I choose not for it to happen here because of the situation here,’ he whispers, afraid the servers might overhear.

The ‘situation’ is the criminalisation of gays and the prescribed fourteen-year jail-term for same-sex marriages, approved by lawmakers and the president in 2014 as a populist gambit ahead of an election they ended up losing anyway. The stunt unleashed a manhunt of suspected gays among the hoi polloi. Folks of means retreated indoors and carried on. Or went abroad.

Chidi refers to his interactions with his foreign fuck buddies as having a ‘coffee and a chat’. But even these trysts are becoming rare: it’s as if he’s weaning himself off men.

It’s a high price to pay in order to function in Nigeria.

Before we rejoin the others I pull him closer for a hug and mischievously whisper, ‘So does this mean there is no more hope for us?’Chidi pulls his head back, takes a good long look into my eyes and bursts into a fit of laugher. And responds, ‘There’s always hope for you! We’ll have a coffee and a chat when we’re in London.’

Months later we chow down on some goat pepper soup, yam and tender guinea fowl at Ikoyi’s Casa d’Lydia. A giddy Chidi is explaining that life isn’t terrible – he wanted kids and now has three. And he’s finally found someone. Someone local. Someone safe. Someone married with children too. His companion is a businessman whose family lives in Sokoto. Weekdays he’s on his own in Lagos. He gets Chidi. Chidi gets him. They are happy.

Categories Africa Non-fiction

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Chike Frankie Edozien Jacana Media Lives of Great Men Nigeria