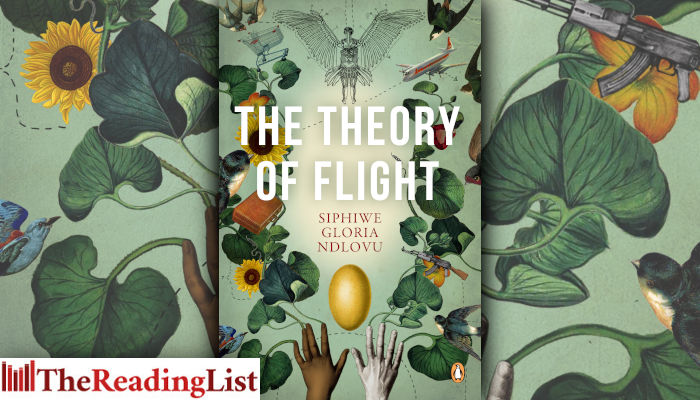

An exciting new African voice – Read an excerpt from Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s debut novel The Theory of Flight

More about the book!

Read an excerpt from The Theory of Flight, the debut novel by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu!

About the book

Said to have hatched from a golden egg, Genie spends her childhood playing in a field of sunflowers as her country reawakens after a fierce civil war.

But Genie’s story stretches back much further: it tells of her grandfather, who quenched his wanderlust by walking into the Indian Ocean, and of her father, who spent countless hours building model aeroplanes to catch up with him. It is the tale of her mother, a singer self-styled after Dolly Parton with a dream of travelling to Nashville, and of her grandmother, who did everything in her power to raise her children to have character.

With the lightest of touches, a cast of unforgettable characters, and moments of surreal beauty, The Theory of Flight sketches decades of history in this unnamed Southern African nation. It does not dwell on what has been lost in its war, but on the daily triumphs of its people, the necessity of art, and the power of its visionaries to take flight.

About the author

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu is a writer, filmmaker and academic who holds a PhD from Stanford University, as well as master’s degrees in African Studies and Film. She has published research on Saartjie Baartman and she wrote, directed and edited the award-winning short film Graffiti. Born in Zimbabwe, she currently lives and works in Johannesburg. The Theory of Flight is her first novel.

Read an excerpt from The Theory of Flight:

Genie’s beginning was like all our beginnings – beautiful and golden.

After spending the night with Golide Gumede, Elizabeth Nyoni felt something give way in the space that he had come to occupy in her heart – it travelled through her body and found its way onto her mattress. When Elizabeth picked it up and placed it delicately in the palm of her right hand, she discovered that it was a shiny golden egg. It was at that moment she realised that her fate was sealed: she was bound to Golide Gumede for an eternity.

Golide Gumede had been born Livingstone Stanley Tikiti. But before he could be born, his parents had to meet. And before his parents could meet, their circumstances had to be such that when they did meet they could actually do something about it.

His father had been born on the Ezulwini Estate and christened Bafana Ndlelaphi. Bafana had had the great fortune of being born within the sphere of Mr Chalmers’ benevolence. Mr Chalmers was a gentleman farmer, and, as such, had had the time to teach the young Bafana how to read and write. He taught him these things not necessarily because he believed that the boy would be able to use the skills when he grew up, but because those were the skills he could teach the boy when he was at his leisure.

As a result, Bafana grew up to be an enterprising young man who was a rare thing for his time: a moderately educated black man. Without much effort he got a job as the assistant of a Greek travelling salesman. Because of this he became an even rarer thing – a black man who had the opportunity to travel the length and breadth of the country. Bafana found that he loved to travel. He marvelled at the often incongruous nature of his country: a raging waterfall, rocks that balanced precariously on top of one another, and a flower that looked like a roaring flame that had once upon a time caught its breath and never exhaled. He often wished he had a way to capture the many sights he saw, but all he had was his memory. In Mr Chalmers’ library, in leather-bound, sombre-looking books, were the journals of great men: David Livingstone, Thomas Baines, Henry Morton Stanley; men who had been able to record what they discovered on their travels. Bafana felt an affinity to these men, these explorers. He felt that he too was an explorer, or would have been had he not had the misfortune of being born in the wrong century. He felt that the name he had been born with, Bafana Ndlelaphi – which literally meant ‘boys, which is the way’ – was not fit for an explorer such as himself and so he changed it to Baines Tikiti. Tikiti – a ticket, something one purchased in order to go on a journey. Something that gave one purpose.

The Greek travelling salesman felt his fortune in having Baines as his assistant. Baines was a natural-born charmer who, even with the limits of language, was able to get the most miserly and frugal woman to reach into that space underneath her left breast that held the grimy handkerchief that held the even grimier sixpence that stood between the woman and absolute poverty. There often was hesitation once the handkerchief had been brought out into the light of day, but after Baines said a few words in the seductive and universal language of commerce, the woman would smile and then nod resolutely before untying the tightest and truest knot, using her teeth and calloused, blunt fingers to pry the handkerchief open and reveal the thing that she had treasured most until that very moment: a sixpence that a husband or son had laboured for in the mines, on farms or in the cities. The once frugal woman would walk away with her new treasures – an oil lamp whose leak she had not yet discovered, a smooth blanket that she did not yet know might pill after its first wash, a dress she did not yet know was either several sizes too small or too big because she had not been allowed to try it on, a mirror whose silver edge would inevitably tarnish, then corrode and rust.

Women, young and old, single and married, abandoned and widowed, loved Baines, and Baines tried to love them in return, but he loved his travel more, and, as a result, he broke quite a lot of hearts. This, however, did not stop him from selling cheap European trinkets to unsuspecting African women throughout the colony.

Then one day Baines and the Greek travelling salesman arrived at Guqhuka – a village that was soon to be turned into the Beauford Farm and Estate – and something very surprising happened: for the first time Baines was not able to charm a sixpence out of a woman’s hand. To make matters even more mortifying, the woman did not have her sixpence tucked away under her left breast; she held it, temptingly shiny and new, between her thumb and her forefinger, ever so ready to give it away, if only Baines would show her something that she liked. He showed her shoes that he claimed were of the finest Spanish leather; she was sure they would pinch. He showed her a mirror; she wondered what possible use her own reflection would be to her, since she already knew herself. He showed her a pair of pillowcases, baby soft pink with delicate lace edges; she wanted to know where the pillows that went inside the pillowcases were (a question that he had never been asked before). Not quite defeated, he showed her the one thing that he thought no woman could resist – a crown fit for a queen, sparkling with rhinestones and the insincere glitter of cheap metal; she asked what kind of queen would wear a crown that only cost sixpence.

It was his turn to ask questions: What is your name? Prudence Ngoma. Where are your people from? Here. You obviously have travelled, where have you been? The City of Kings. Would you marry me?

An arched eyebrow let Baines know that she had heard his proposal. She asked him a question in return. Where are you from? Ezulwini. I have never heard of the place. But she said this in such a way that he knew she would not mind hearing more about the place and seeing it for herself some day. They married soon after and settled in Ezulwini.

The temptingly shiny and new sixpence never passed from her fingers to his.

Categories Africa Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts New books New releases Penguin Random House SA Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu The Theory of Flight