‘A Woman’s Place is in The Struggle’ – Read an excerpt from The Knock on the Door

More about the book!

Pan Macmillan South Africa has shared an excerpt from The Knock on the Door: The Story of the Detainees’ Parents Support Committee, by Terry Shakinovsky and Sharon Cort.

The book tells the story of those who helped draw international attention to the atrocities being perpetuated against children – some as young as nine – by the apartheid state.

Click on the link above for more about the book.

The Knock on the Door will be launched on Tuesday, 27 February 2018.

Read the excerpt, take from Chapter 19 of the book:

A Woman’s Place is in The Struggle

‘We as women say: “Away with the state of emergency.” Unban the organisation of the people and give our leaders back to us.’

– June Mlangeni, FEDTRAW, Press Conference, 11 December 1987

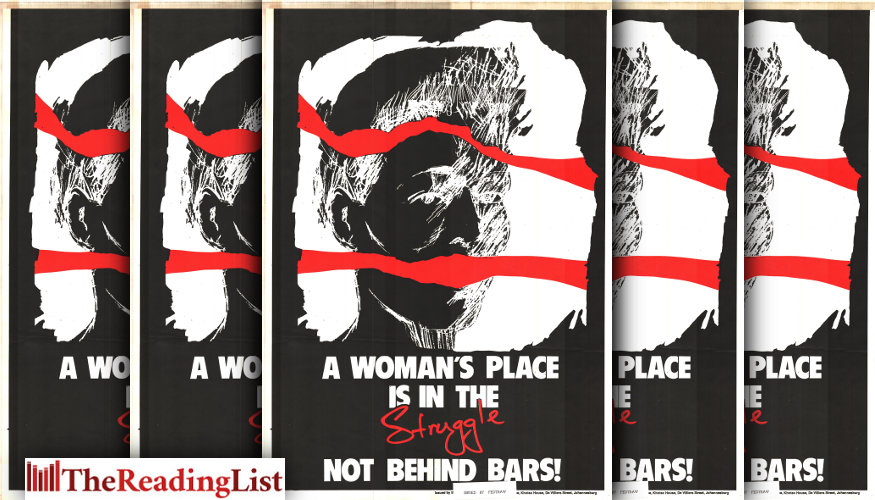

Like so many South African women, Daphne Mashile faced additional burdens in detention because she was a mother. In late 1987, the DPSC began collating women’s personal stories of repression and detention for a publication, A Woman’s Place is in the Struggle, not Behind Bars. The DPSC then declared February 1988 as the month of Women and Detention. The organisation wanted to highlight the torment of women – those held in detention as well as the mothers, wives and sisters of prisoners. While the security police brutalised all detainees, women were subjected to particularly sadistic methods of torture and abuse of their womanhood.

Research for the publication revealed that sexual violence and humiliation were at the core of most interrogations of women. What women feared most was being raped. The security police deliberately used the threat of rape to force confessions out of female detainees. Many women and even teenage girls were, indeed, raped, and were too ashamed and fearful to report the offending policemen.

Endless accounts of insidious forms of sexual harassment and the conscience of the nation innuendo emerged, not all of which were documented in the publication. Women gave accounts of being kicked in the genitals, having their nipples electrocuted and being invasively touched while their hands were tied behind their backs.

Jennifer Schreiner was assigned an interrogator who had a reputation in Cape Town for torturing women. ‘He had stripped women naked. He had threatened Shahida Issel that if she didn’t co-operate he would go and rape her daughter. He had threatened to take me into the rural areas where nobody would know what he was going to do to me.’ It was part of a torturous game that emphasised the physical power men had over women.

Female jailers also used sexual humiliation as a tactic. At jails around South Africa, it was routine for women to be ordered to strip naked and to have their vaginas searched for contraband items. Connie Bapela recounts what happened after she and comrades smuggled matches into jail with which to stage a protest at their continued detention: ‘They took all of us to the punishment cell, the Kulukulu. Before you entered the cell, the female warders put their finger inside the vagina looking for matches, and the men were just watching.’

Women spoke about the humiliation of menstruating, particularly when they were denied sanitary pads and their bleeding was obvious. In some instances, ordinary policemen were more sympathetic, as Connie Bapela describes: ‘When I was menstruating … we tried by all means to create this relationship with the policemen – the black ones – so I gave them money to go and buy me some pads and they did. They would just say, “Eish … but why were you detained? You are so young. We don’t understand.” I tried to educate them but it was difficult in prison.’

The security police also tortured women psychologically, often playing on their status as mothers. They tormented them by telling a woman’s place is in the struggle them that their children were ill or were going to be put up for adoption. Manipulating feelings of guilt, the police offered to release the detainees if they provided them with information about other activists. Women who weren’t married or didn’t have children had aspersions cast on their desirability. Jenny Schreiner tells how she was confronted about being single: ‘“What’s wrong with you? You are 30 years old. You don’t even have a boyfriend. You don’t have kids. Is that why you got involved in politics?” Then when you are alone in your cell … you discover that they had planted in you that seed of doubt about your single, childless status despite the rational part of your brain saying what reactionary stereotypical issues these are.’

Other detainees faced savage physical assaults. ‘There was this notorious policeman by the name of Rede. They took me to some river and beat me to a pulp. I couldn’t walk. I started to menstruate and they threw me into the river,’ says Doris Mahloko. She testified that she was so badly beaten that she was left infertile.

Pregnant detainees were particularly vulnerable. Connie Seoposengwe remembers: ‘I was the only one left in the whole female section, a big section, alone as in alone. The prison warders would knock off at half past three, lock my door and they’d be gone. I’d see them in the morning. So my fear was, “What if I bleed in the middle of the night?” because my conditions were not okay for a pregnant person. A pregnant woman must be home, must be taken care of, must be loved. She must not go through what we went through … a whole pregnancy there.’ Connie falls silent as she remembers, and then continues: ‘There is nothing as painful as solitary confinement. It’s even worse when you are pregnant. I wasn’t the only woman who endured that.’

Deborah Marakalla, a worker at the Black Sash office in Tembisa, Gauteng, had to endure what Connie feared: a medical emergency the conscience of the nation alone. When Deborah miscarried, she was by herself in her cell, and nobody responded to her screams for help. She was fortunate that she did not die, as her situation was life-threatening: ‘I was about three months’ pregnant, but I lost the baby because it was inside my fallopian tube and the tube burst.’

Birth in detention carried other horrors. Kate Serokolo gave birth with a group of policemen in attendance. ‘Dr Van der Walt asked those soldiers to move away from the room because he said, “I cannot help this woman with you around.” They were all men. They refused. I heard them talking over the radios and then afterwards they told the doctor that they had to be there. They stood there … and I gave birth in their presence – looking at me, laughing at me when I was having labour pains. I was like a joke to them.’

Activist Nomvula Mokonyane, who would later become the premier of Gauteng, gave birth to her son in detention. An SABC report on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission said: ‘Nomvula Mokonyane was arrested and put into solitary confinement 11 days after her wedding and two months into her pregnancy. The district surgeons disputed the fact that she was pregnant. They said that her fallopian tube was blocked “and they had to make sure that they unblock them so that then you can begin to have menstruations; and if you begin to resist that then torture will take its own course”.’

When Nomvula was released she was placed under a restriction order. She had nowhere to live and no money to return home. Daphne says she came straight to the DPSC office and the staff found her a place to stay. ‘We had to look for accommodation in a church. It was communal and there were a lot of displaced families there. We then had to look for families that were sympathetic around the church to at least keep the baby overnight and Nomvula would go and breastfeed the baby in the morning. I asked Max for money for nappies. Then we went to the Black Sash and the ladies brought clothes for the baby. Still today, Nomvula will tell you, “I owe my life to the DPSC.”’

Although women were in a very vulnerable situation, they fought back. Connie Bapela was detained for over three years. She and her comrades set their mattresses alight to protest their detention. ‘We planned the protest because we wanted them either to charge us or release us. They used to take orders every day for us to buy from the shop. We bought some tinned stuff and each and every one of us bought matches. It didn’t strike these policemen why we were buying matches. When they locked us up at 3 o’clock after supper, we started burning things and breaking the windows. We called this Operation Phambane [Operation Madness]. They called strong white policemen. They put water and tear gas in the cells.’ A week later, on 5 December 1988, Connie was released. She was not charged but was subjected to further restrictions.

On 24 February 1988, the government delivered its harshest blow yet to the DPSC. In the biggest political crackdown in ten years, 17 anti-apartheid groups were effectively banned, including the DPSC and DESCOM. In issuing the order, Minister of Law and Order, Adriaan Vlok, declared that anti-apartheid groups had created ‘alter- native strategies’ to deal with the state of emergency. According to Vlok, anti-apartheid groups not only engaged in violent acts, but their activities made the country ungovernable. Publicising human rights abuses was clearly seen as one of the activities dangerous to the state.

The DPSC could no longer issue its long-planned booklet, A Woman’s Place is in the Struggle, not Behind Bars. Instead, the campaign continued and the publication was issued by the Federation of Transvaal Women (FEDTRAW). This organisation was formed in 1984 and brought together women’s organisations from all over the a woman’s place is in the struggle former Transvaal province (currently Gauteng), in order to give voice to the diverse issues affecting urban and rural women.

The February 1988 decree prohibited the DPSC and 16 other organisations from ‘carrying on or performing any acts whatsoever’. Max Coleman said of the decree, ‘To oppose it [the Act] is to invite liquidation.’ Even so, members of the DPSC refused to stop the organisation’s work. Instead, they continued to seek ways to over- come repressive government legislation. The DPSC would continue its effective monitoring of state repression, mobilisation of communities and detainee support work under a new guise. Two new organisations, the Detainees Aid Centre and Human Rights Committee, would emerge from the now restricted DPSC.

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Sharon Cort Terry Shakinovsky The Knock on the Door