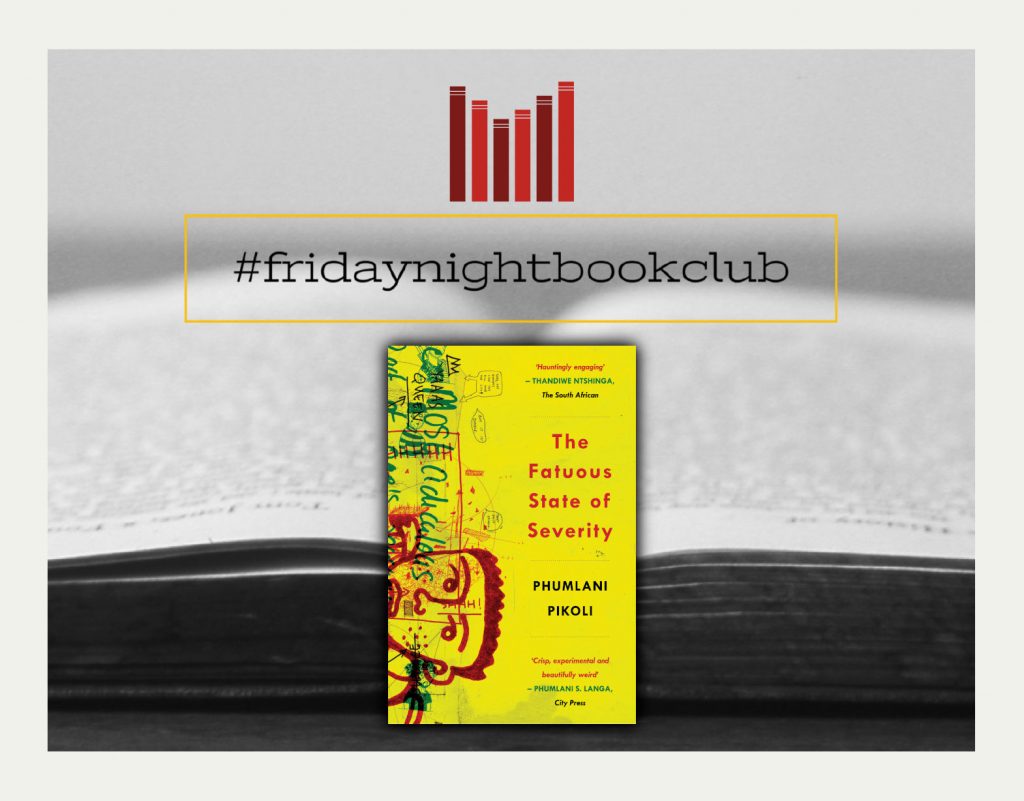

The Friday Night Book Club: Read ‘My Beautiful Little Boy’ from Phumlani Pikoli’s book The Fatuous State of Severity

More about the book!

The Friday Night Book Club: Exclusive excerpts from Pan Macmillan every weekend!

Staying in this evening? Settle in with some popcorn and this extended excerpt from Phumlani Pikoli’s debut short story collection, The Fatuous State of Severity.

About the book

The Fatuous State of Severity is a fresh collection of short stories and illustrations that explores themes surrounding the experiences of a generation of young, urban South Africans coping with the tensions of social media, language insecurities and relationships of various kinds.

Intense and provocative, this new edition of the book, which was first self-published in 2016, features six additional stories as well as an introductory essay on Pikoli’s publishing journey.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

My Beautiful Little Boy

‘Buthi, are we really so special?’ I asked my older brother, as he held my hand and guided me cross the road.

‘Of course we are!’ he said as we stepped onto the pavement on the other side. He looked down at me and touched the back of my head; he knew I really liked it when he put his hand at the back of my head. His hands felt soft on my head and hard in my hands. I felt myself shiver with joy and he laughed.

My brother always picked me up from school. This was one of the rare times we got to spend with each other. Since Mommy and Daddy decided to live in different houses, we no longer lived in the same house.

‘Bafana needs his mother,’ I heard Daddy say to Mommy. I was feeling hot and my eyes were sore. Iwas outside their room, listening to them talk, before Buthi picked me up and took me to the movies. ‘You know you’re special, Bafana, why you asking me such a silly question?’

I wanted to look up at him, but the sun hurt my eyes and I put my hand up in front of them to stop it from making them sore. Buthi touched my head again and then took off his cap and put it on me. It covered my whole face and it was dark before he lifted the brim in the front and told me to hold it up. I was laughing ’cause he was laughing. Then he made it right at the back and I could feel it squeezing my head. It pinched me, but when he asked how it was I said it was perfect because I never got to wear his clothes. They were always too big for me. This was my chance. He smiled and told me I looked like a gangster. I told him I was a gangster. Then he asked again why I’d asked him that question about being special.

‘I don’t know …’ I said. ‘It just feels like people are always looking at us.’ He smiled at me. It wasn’t a happy smile; it was a smile I had seen on Mom and Dad a lot when I asked them about things they didn’t want to tell me.

‘That’s a question for when you’re big, Bafana …’ Mommy would say and then she’d tickle me and make farting sounds on my stomach with her mouth. I would laugh so much that I’d end up really farting. Then she’d tell me she couldn’t be around stinky young men, put two of her fingers on her nose and run away from me.

Daddy told me that some of the answers I was looking for would just make me sad. ‘You’re my happy little boy. I want you to stay like that,’ Dad liked to tell me, and then he’d kiss me on the top of my head and walk away.

Buthi told me we could take the long way home today. He said we could walk down my favourite street. He had my bag on his back, but still he lifted me onto his shoulders. I was very far from the ground and I wasn’t even scared. It was hot and Buthi’s head was a little bit slippery but I didn’t care ’cause I was on top. He walked so fast with me and my backpack on his shoulders.

‘Close your eyes,’ he told me when we were getting close. I closed them, because I wanted the street to also surprise me.

‘Okay, open them.’

Everything in the street was purple, the trees nice enough to give the street their flowers. They even gave the grass some flowers. But it was because the trees had so much, I think that’s why they were so nice.

‘I love purple so much!’ I shouted.

Buthi said we should take a rest on the grass. When he let me down, he used his arms to make me somersault onto the grass. Then he lay down next to me. The flowers smelt so nice and the grass too. We just lay there … We didn’t know whose garden it was; me and my friends had been chased away from other people’s gardens, some shouted and told us they would use their dogs next time. But Buthi was big. It was definitely okay with him here. ‘Buthi, why did you ask me why I asked what I asked you?’ I asked him.

‘Why are you asking me why I asked you what you asked me?’

‘Because you asked me why I asked you what I asked you.’

‘So now you’re asking me why I asked you why you asked me why I asked you about what you asked me?’

‘Uhm …’ I had to close my eyes and try to understand everything he had just said. This game always made me confused because Buthi was so much gooder at it than me.

‘Yes!’ I shouted out when I finally stopped being confused. Lying down, we were both looking up at the nice trees that liked to give away their flowers. Through their branches we could see the blueness of the sky. It felt like we were seeing magic.

‘Yes what?’ Buthi asked.

‘Yes to what you asked me!’ We were laughing so much today. I decided to sit up, on my bum. Buthi was still lying down when I tapped him on the shoulder to show him.

‘See how all those people are all looking at us now.’ I pointed. He kind of came up on his elbows to see the passing group. They were from the Afrikaans school not far from our house. They looked and also pointed at us. I remember asking Mommy and Daddy why I went to school so far when there was one around the corner. They just smiled at me.

Buthi looked at them. Then he waved at them and smiled. They stopped and looked at us when Buthi did this, and instead of waving back they started to run away. Buthi looked at me and smiled; it wasn’t a happy one. I asked him why they were always looking at us.

‘It’s because we are very special, Bafana.’

‘So, I should be happy about it, Buthi? ‘Cause a lot of the time that they do it … it makes me feel funny.’

Buthi sighed and sat up to look at me. He took his cap off my head and touched the back of my head again. My whole body shivered and we laughed.

Then he told me.

‘Bafana, there’s something you’re going to have to learn sooner or later. And that is that some people don’t like you and it’s not your fault.’

‘What do you mean they don’t like me, Buthi? Was I ugly to them, Buthi? ‘Cause I can tell them I’m sorry and that I didn’t mean it.’

Buthi’s eyes looked like they were sore but he was smiling. ‘You didn’t do anything wrong, Bafana. You were born the most beautiful boy in the world.’

I was very confused by what Buthi was saying. Because if I was the most beautiful boy in the world, wouldn’t that make people like me more?

‘Wouldn’t they love me for being beautiful then?’ I asked him. I didn’t mean to make him laugh, but he did. He laughed a lot. He laughed so much that he looked like he was crying.

‘Did I make you sad, Buthi? I’ve never seen you cry.’

Buthi stood up and took me in his arms and hugged me tight. I think I heard him sniff. Then suddenly he squeezed me and I couldn’t breathe. I tried to tell him, but then he let me go and we laughed. ‘You know, Bafana, there’s nothing wrong with people not liking you sometimes.’

I didn’t know what Buthi meant when he said this to me, but it didn’t sound right. Why would it not be wrong for people to not like you? Only bad people didn’t want other people to like them.

‘But then wouldn’t that make me a bad person, Buthi?’ I asked, looking up at him from where I was lying in his lap.

‘What is a bad person, Bafana?’

‘Someone who is ugly to other people. Someone who cheats, lies and beats people up. Someone who hurts other people.’ It was so easy to answer his question. Why did he want me to answer something he already knew?

‘I see …’ said Buthi. He had his naughty smile on – I knew it was time to play a game.

‘Let’s play a little game, Bafana …’

‘Okay,’ I told him.

‘I’m gonna ask you some questions and then you have to answer them, okay?’

‘Okay.’

I always want to answer Buthi’s questions.

‘Remember that time we played Crazy 8 and after I won I showed you that I had hidden my cards under my bum?’

‘Yes, you cheated me! And then you didn’t tell anyone that you cheated me! You lied and everyone believed you, and then you and Nomvundla teased me until I became so angry that I threw you with the remote and then you hit me! I’ll never forget that!’

‘I hurt you a lot that day.’

‘You did,’ I told him. I felt sad and angry at the same time, like I did that day. Buthi was so mean and ugly that I thought I would hate him forever.

‘Do you think I’m a bad person?’

Of course I didn’t think that Buthi was a bad person. He was my most favourite person! But how was he not a bad person if he could do all those bad things to me? I couldn’t think so fast. I could only stare at Buthi. I tried to open my mouth …

‘And what about you, Bafana? Remember, you also shouted at me, which is ugly, and you threw the remote at me, trying to hurt me.’

He spoke in a soft voice that let me know he wasn’t angry, but he still had his sad smile on his face. I felt sad and wanted to cry. Sometimes I get so angry that I don’t know what happens to my body and I just try to hit everything and break things. Buthi is right, I am a bad person.

‘Maybe I am a bad person, Buthi,’ I told him. I sniffed, wrinkling up my nose, and playing with the grass in my hands. I couldn’t look at him any more.

‘No, Bafana …’ Buthi told me, with a finger under my chin so my eyes and his were looking at each other. ‘You’re not a bad person. It’s not always easy to know who’s good and who’s bad. Those children don’t like you because their parents have been taught to hate our parents. And their parents teach them to not like us. Eventually they’ll probably hate us, just like they have been taught to hate our parents.’

I didn’t really understand what Buthi was trying to tell me, ’cause … ’cause … At my school I had friends who spoke Afrikaans at home and they liked me, and also our parents liked each other. When I asked Buthi about this, he smiled.

‘Remember what I said earlier about not everyone liking you?’ he asked. ‘Well, keep that in mind, because not everyone is the same. Some people are nice, others are ugly, and some ugly people are pretending to be nice and there are nice people who you think are ugly. As you learn, Bafana, you’ll come to know the difference,’ he told me and pushed me gently down onto the grass. He lifted my untucked shirt and tickled my tummy gently with his fingers. I was looking up through the purple-spotted branches at the sky and enjoying his touch. I watched, through the purple lace curtain, the white clouds swim in the blue sky. I didn’t really understand what Buthi was telling me any more, but pretended to. It sounded like he was trying to tell me something important. As I listened to his voice, I thought of the older sister of my bestest friend at school, Kyle. I really liked her face. I told Kyle this once and he said something about my mother being pretty for a black. When he said that, it made my stomach feel funny, but it sounded like a good thing and I agreed with him. Buthi was still talking, and I tried to listen to what he was saying.

‘… You see, Bafana, they’ll end up trying to tell you that it’s because you’re different. It won’t be because of that. It’s going to be because they’ve come to believe things about you before they even met you. They’ll try to make you believe that you’re the same as others, or single you out as a special case that makes you better than others. But you’ll never do that. You’ll refuse to be what they want you to be.’

I was so confused. I was angry with myself for allowing Buthi’s tickles to distract me for so long. I didn’t know what he was talking about and he was talking to me like a big person – he never did that. I didn’t know what to say, but I knew I had to make him believe that I was listening.

‘Why?’ I asked him.

He sighed a deep sigh. He asked me to sit up and look at him. I knew when he did that he knew I wasn’t listening any more and was going to tell me to pay attention when we were talking. I sat up on my bum and faced Buthi. I remember how sweet the grass smelt, the purple flowers also giving it a soft perfume. It was a hot day, but nice in the shade. When I finally looked Buthi in the face, I saw his eyes were red. I had made him really sad. He wasn’t even smiling a sad smile. I was angry with myself for not having listened properly.

‘I’m sorry, Buthi,’ I started, but he didn’t let me finish.

‘Bafana, you’ve got nothing to apologise for. Not to me or anyone.’ Buthi’s voice was shaking and he was barely whispering. I could feel the back of my throat also getting sore. As he opened his mouth to speak I could see his lips wobble and he took in a deep breath. He had tears rolling down his face and he sniffed.

‘You’re not going to be anything anyone else wants you to be because you’re my little brother. You were born beautiful and you’re going to stay that way no matter what anyone tries to do to you. I love you for the person you are, not for what the world will try to turn you into.’

When Buthi hugged me I couldn’t help myself. I started crying into his tummy. My whole body was shaking. I could feel Buthi’s body shaking too, but his tight grip let me know that I was safe, so I carried on crying like there was nothing wrong. When we finally stopped crying, Buthi slowly let me go. But I didn’t let him go. I stayed in his lap and closed my eyes for a little bit, feeling like the most beautiful little boy in the world.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Friday Night Book Club Pan Macmillan SA Phumlani Pikoli The Fatuous State of Severity