Read an excerpt from Born to Kwaito – ‘Yizo Yizo: The Poetry of Dysfunction’ by Sihle Mthembu

More about the book!

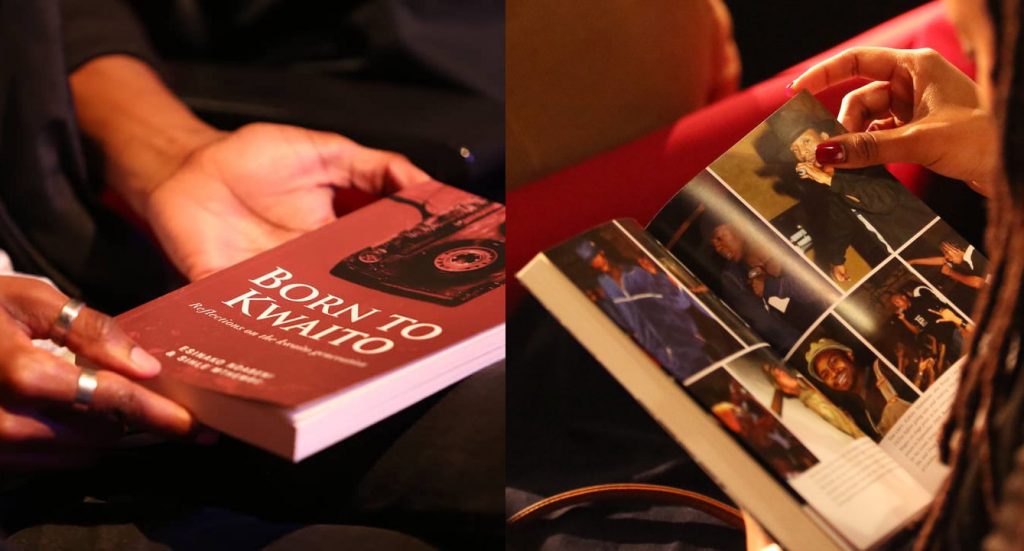

Header image: Born to Kwaito on Twitter

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Born to Kwaito: Reflections on the Kwaito Generation, a new BlackBird Books publication by Esinako Ndabeni and Sihle Mthembu.

The book was launched at the SABC in Auckland Park on Thursday, 5 July 2018.

Born To Kwaito considers the meaning of kwaito music now; its place in the psyche of black people in post-apartheid South Africa.

The book consists of a collection of essays, including candid and insightful interviews from the genre’s foremost innovators and torchbearers, such as Mandla Spikiri, Arthur Mafokate, Robbie Malinga and Lance Stehr.

Thabiso Mahlape, BlackBird Books publisher, says: ‘Born to Kwaito is not only an examination of the history of the music genre; it is also a revisit of the relationship we have with the music, its stars and their own relationship with their art and themselves.’

Read an excerpt:

Yizo Yizo: The Poetry of Dysfunction

Sihle Mthembu

‘Ekasi we don’t wear gloves when we do the dishes,’ she says before breaking into laughter, like she just opened the door into a secret inside joke for which only she has the keys. Thembi Seete is a South Africa canon bomb. She’s one of the last survivors of kwaito-era cool at its peak. The last woman standing from an entire generation of leather-wearing, Chuck Taylor-stomping sonic insurgents. Right now, however, she is not her commanding Boom Shaka tour-de force self. Not the Thembi we know from pre-Y2K videos as the Thelma to Lebo Mathosa’s Louise.

She is seated in her Jozi home, reclined, taking it easy and talking about one of the projects that has defined her almost two-decade long career. ‘It’s a silly thing to think you can have a show about the township where you have the characters washing the dishes wearing gloves. Our show was a game changer in that it took away silly little things like that. He brought us in and we got into the details and knocked it out of the park every week,’ she says, a hint of seriousness breaking through the humorous demeanour she had just a second ago.

The show in question is Yizo Yizo, that once-in-a-generation flag-bearer for a surprisingly South African form of nihilism. The cinematic invasion that, for three seasons dominated our small screens and offered a rare, unfiltered view into the rape, crime, slang and the various template characters that were the bedrock of townships around the country.

The man who Thembi is speaking about and the silent puppeteer behind this show’s rock n’ roll journey, is Angus Gibson, a medium-sized character who is little known outside of South African TV circles. Safe shoulder-size, not broader than what you’d expect from a braai-eating, camera-wielding, cinematic clairvoyant. He is a smuggler of cultural contraband and the soothsayer of South African paranoia. Gibson is the surprisingly human figure that is the real hero behind this story. His physical presence does not do justice to the weight of his name every time it flashes when the credits roll on local television.

With smooth, thinning white hair that sits just at the shoulders, Gibson is controlled and contemplative. He talks with the kind of self-awareness that can only be mastered by someone who secretly knows something known by nobody else in the room. And it was he who, along with long term partner in crime Teboho Mahlatsi, coordinated the most impressive mess in South African television history. Gibson tells me the story of how the iconic Yizo Yizo came to life:

Teboho and I had been writing a vigorous, funny but wild feature called Streetbash, set in the basement of a downtown building. Our partner, Isaac Shongwe, who was unnerved by Streetbash’s nihilism, suggested that we do something more constructive and pitch for an educational drama which SABC 1 was commissioning. We agreed that we would do it on the side. We put together a team of interesting people, none of whom had written or worked in television drama before. Teboho and myself were from documentary backgrounds. Peter Esterhuysen had written textbooks and comics. Mtutuzeli Matshoba had written short stories and Harriet Perlman had edited Upbeat, a youth magazine. We started assembling ideas in the downtown basement, sticking cards on the walls. We assumed it would take just a few months of our lives. It ended up consuming most of the next seven years.

The Laduma Film Factory (As Bomb Productions was then known) won the bid and was given carte blanche to create a TV series that addressed education issues in schools. But the programme that came out of what was a relatively straightforward brief, was both necessary and otherworldly. Set partially around Supatsela High School, the show dives into the depths of the education system and the effect a broken-down school system can have on its surrounding community. Yizo Yizo is a visual poem. The show’s first season is an elegy to the death of hope and the need to face up earnestly to the cancerous uncertainties that were eating away at our rainbow nation dream. The most surprising thing about watching the show now is how well it holds up. Its themes of desparate youth, communal collapse and social uncertainty are as relevant now as they were when the series first hit the small screen. Gibson reflects:

It set out to draw attention to the crisis in the township schools and I think it was successful in that, although some people suggested that the crisis was heightened by Yizo Yizo itself. In the context of local black television that had gone before, people were mixing language for the first time, using slang, swearing. The more experienced members of the crew were often horrified by what was happening in front of the camera. The style and the content broke many rules that they believed were sacred. Again and again young people were saying that they were seeing themselves reflected on the screen for the first time.

Despite the fact that The Bomb Shelter Film & Television Production Company has gone on to create interesting content in the form of shows like Zone 14, Isibaya and Isethembiso,Yizo Yizo continues to be their magnus opus. It has been studied by academics and lionised township Iscamtho. More than a decade after the last episode was aired the SABC, in its usual scramble for relevance, has reverted to re-screening the series, repeatedly airing late-night reruns of the seminal programme. These are all merely the byproducts of making a show that canonised a moment. Perhaps it’s bad form in journalism to talk about your own experience in a story, but indulge me for a moment. It’s worth mentioning that for the so-called Generation X, South Africans who came of age in Mbeki-era Mzansi, Yizo Yizo was the first taste of a thing going ‘viral’. I remember skipping school with my friends and catching a rerun of the episode that had Ronnie Nyakale’s Papa Action being sodomised in prison by Nongoloza played by Israel Mokae. If you were young, black and ‘with it’ in ekasi, you did not experience the early 2000s properly unless you had at least one copy of Yizo Yizo taped via VCR, which you would play with your friends when the parentals were away.

Watching the show back then was a hyper-real experience bordering on the surreal. With its awkward angles and extreme close-ups, zooming into faces sweaty with the Daveyton heat, it felt like a hallucinogen-induced dream every time. But it wasn’t. It was just Gibson and his township requiem strumming their guitars and cameras for a cinematic nightmare. Blackness had never been framed so closely, so terrifyingly, so beautifully. It felt both like baptism and drowning. About the approach to narrative and cinematography they chose to use Gibson says:

At the time we were very influenced by Asian cinema (Wong Kar-wai and Satyajit Ray), and shows like Homicide – all of which explored the handheld camera and had an honest kind of documentary feel. We were of the opinion that the ‘Rainbow Nation’ was a con. Our nation was in an extraordinarily aggressive moment and we were not acknowledging it in the media. We wanted to provide what we thought was a more honest view.

Sthandiwe Kgoroge was one of the first people cast for the show, and went on to win an Avati award for her role as Miss Cele, the eternally optimistic new teacher who finds herself thrust into the mess that is Supatsela High. The accomplished actress says she thinks that the reason Yizo Yizo hit home was because of the production team that was behind it, as much as it was due to the courage of the cast to get in front of the story. Yizo Yizo was ground-breaking for South African television.

‘I sincerely believe we need more dramas like that; stories which don’t sugarcoat reality and give the youth a false sense of what is happening. The SA industry needs to stop being so PC,’ Sthandiwe says, sounding slightly irked by the humdrum of it all. ‘I played a pretty straight forward character and I didn’t really get any funny reactions from audiences, just encouragement. But what I missed most about being on that set was the energy. Everyone there was excited about what we were doing, therefore we gave our best,’ she adds.

Part of Gibson’s genius is a Steve Jobs kind of thing. He has Jedi mastery in surrounding himself with people that are infinitely talented; some perhaps much more than he. Mthuthuzeli Matshoba was easily one of the more inspired choices. A short, stoutly built man with the weather-beaten smile of an activist and an almost roundish belly, he seems like a father figure for both good and bad behaviour, depending on whom you ask. And it is he who should be given credit for adding value to the authenticity that the show is known for. After several months on the road doing research in schools, he presented some of the gangster elements that would later become part and parcel of the Yizo Yizo legend:

We started by researching the school situation in Soweto, visiting schools and interviewing kids about their experiences. Bullying, rape, teacher-student affairs and all that. We would then spin anecdotes around the research, write step outlines and then write two or three episodes each at the same time. It wasn’t much of a problem for Angus as he spent a lot of time among the rank and file of Soweto. Once, his car was hijacked but he got it back within an hour because of our connections.

Elaborating on the work done behind the scenes, the writer observes:

The relevance of Yizo Yizo was that it was inspired by reality. The characters were based on some members of a feared Mzimhlophe (Orlando West) ‘boy bandit’ gang who called themselves The Hazels, after a pretty, streetwise girl called Hazel who was every gangster’s dream girl. Let me risk coming across as arrogant and say that I was the ‘township guy’. I had grown up with the Hazels and other Soweto gangs and had a front-row perspective of their reckless escapades, like raiding schools for girls. I knew how township delinquents thought, felt and lived because I was an interested short story writer for Staffrider Literary and Art Magazine for a long time. I provided the anecdotes and the three of us weaved them into screenplays.

After an initial screening of Yizo Yizo with musos from Ghetto Ruff, someone described the show as ‘the bomb’, and thus Laduma Film Factory morphed into The Bomb Productions and later, The Bomb Shelter. That, ‘u grand Joe?’ line you hear at the end of every episode is actually a line said by Sticks to Thulas in season one of the series.

Even the show’s name pays homage to a very specific township dialect which is both unique and generic. The name Yizo Yizo means nothing in particular, but it can be reconfigured to mean anything from, ‘It’s on’, ‘For sure’, to a pre-Wacko Jacko version of, ‘This is it’. It’s all about context, which is something that is at the core of the show. Gibson says:

We were thinking about names. One morning Teboho said to me that he had heard this phrase ‘yizo yizo’ in a song and it kind of meant, ‘This is it’ or, ‘This is the real thing’. We never doubted for even one moment that we had found the right title. We also liked the way the words looked and together we fought all the naysayers who tried to persuade us to drop it.

Yizo Yizo gave us some of the most memorable scenes in the history of Mzansi television. Who could forget Bobo seeing a cow after taking some drugs in season two, or Chester handing out exam papers after a teacher forgot them at a bar? Dudu being raped in a chicken den is one of the most harrowing renditions of a crime that has been enacted on the small screen in the history of South African TV and film. Through innovative sequences like this, Yizo Yizo de-sanitised the happy-go-lucky imagery that post-1994 South Africans had built about and around themselves.

It went against the grain of the invasive, orchestrated hope that was being churned out by South Africans singing Shosholoza in Castle Lager adverts; that single-story narrative that was cultivated in the euphoria of an idealistic, fleeting socio-historical moment. In those heady days, when singing the national anthem at school was still good form, we were a nation numbed by our own optimism.

With the backdrop of that pervasive feel-good era ushering in the ascension of former president Thabo Mbeki to power, Yizo Yizo came in from the cold like an unwelcome relative with dirty shoes. The relative who paces restlessly in your living room and starts talking inappropriately about family dirt, uncovering decades-long stains hidden from view, disturbing the false peace and pointing out too loudly that the emperor is, in fact, naked.

Gibson is also not unaware of the trauma some of the actors experienced during the filming of difficult scenes:

The rape scenes were difficult and quite traumatic for the actors. Scenes of consensual sex were a whole lot easier. We were encouraging a lot of improvisation in all the scenes. The actors really owned their characters. The rape that happened next to the cage of chickens started with an observation of the way in which the chickens attacked their food. There was a kind of aggressive madness to it that was the clue to the scene. Ernest Msibi, who played Chester, took on that madness and the scene took off from there. It was very scary and it took some days for the actors to get over that. The broadcaster usually stood by us, but I do remember negotiating the number of thrusts there could be in the sex scene between Javas and Nomsa in season three.

By unflinchingly depicting people in a township getting on with the everyday business of being themselves without the overarching gaze of whiteness, Yizo Yizo showcased that we were and are not as integrated as those Castle adverts had been leading us to believe. To say that Yizo Yizo is the greatest TV series of all time would sound hyperbolic to some, but what is certain is that in South Africa, the show provided a much-needed departure from the drib-drab, pedestrian television that had taken over in the ‘reconciliation’-fuelled 1990s. It served as a marquee for teaching audiences how entertaining self-reflection could be. A marquee that was later occupied by the likes of Gazlam, Tsha-Tsha, and, to a lesser extent, The Lab and Home Affairs. And yet this depiction of what was real could not be done haphazardly, as writer Matshoba explains:

School rape was an epidemic at the time and the brief had prescribed that we represent reality. The choice was between downplaying the situation or telling it as it was. We chose the latter. Sometimes shock treatment is the best way to draw attention to serious issues. The biggest challenge was to avoid caricature, or put another way, not to lose the context of reality by creating unbelievable or fake characters. There were some bad characters, like Papa Action, who were repugnant, who we had to write in such a way that the viewers would be compelled to watch because they were an integral part of the story. But the challenge of being careful not to create bad characters who could simply be emulated by young viewers remained always before us. There were many challenges.

It seems to me that often, in critiques of Yizo Yizo, the show does not get due credit for its depictions of the complex nature of black male friendships. Consider the bonds between Papa Action and Chester, and how, through the promise of power, they are able to lure Thiza into their circle. The series showcased the reality of how young men, feeling disconnected from their society, often feel the only way they can bond with each other is through violence.

Yizo Yizo was also the launching pad for many of South Africa’s now recognised acting talent, some of whom later left the show like an exit wound made by a bullet from Chester’s 9 mm chamber. They have since grazed on greener grass. Fana Mokoena on The Lab and State of Violence comes to mind, before his latest incarnation as an EFF member of parliament. Sthandiwe Kgoroge, in the dual role of the twins Zinzi and Zoleka on Generations, as well as a lead role in 90 Plein Street, is another example.

Contrary to popular belief, however, not all of the show’s actors were street bums before making it onto the show. Some of them had actually worked as extras and even in community theatre. But for many of them, including the likes of Tshepo Ngwane who played Thiza, it was through a small agency and the grand lady of South African comedy, Lillian Dube, that they found themselves thrust into the Yizo Yizo limelight. Ngwane recalls how he got his big break:

I had just moved from Newcastle to Jozi to come and stay with my dad. I had told him I wanted to do acting but he really didn’t believe in that because he worried about how I was going to earn a living. So I ended up studying full time and secretly taking weekend classes and acting workshops whenever I could. I was lucky that Mam’ Lillian Dube embraced me. I was just passing by one day and she told me there were these auditions in Rosebank. I immediately caught a taxi and went there and auditioned for the role of Sonnyboy, the taxi driver.

Four days later he got a call-back, and after three call-backs Tshepo didn’t get the role of Sonnyboy. Instead, he was cast as one of the leads in the series. With a fade S-curl (which he later shaved off for his role), Ngwane found himself thrust into what undoubtedly became the defining role of his life. But there was one problem; his old man still didn’t know he was working as an actor now. A taxi-driving, conservative Zulu man, he had no time for watching TV. ‘My dad didn’t even see the first episode. He was told by his taxi driver friends that they had seen me on screen, congratulating him on having a son on TV,’ Ngwane recalls, laughing. ‘I then lied and told him that I was just lucky, that some people had come to school hosting auditions for the show and I got the part. I had to downplay it as much as I could.’

But when the old man saw his son’s acting, he accepted the situation and even started taping the show. Who knows, maybe he is the one responsible for all those VCR leaks of Yizo Yizo that were on heavy rotation around 2000? For Thembi Seete the journey to getting cast was similar, but having to give up the Boom Shaka ‘image’ and make room for a vulnerable character like Hazel in season two, was not easy:

I had seen Yizo Yizo 1 on what was still called Simunye back then (SABC 1 aka Mzansi fo Sho). I was at a crossroads because Lebo was now doing her own thing and Boom Shaka was not that active anymore. So I spoke to Speedy (from Bongo Maffin) and he introduced me to Mam’ Lillian. The first thing I told her was that I wanted to be on Yizo Yizo. Auditioning for the show was one of the craziest things I’ve ever done because I spoke to Teboho before I even went in. I told him to just give me a chance because I was coming from music and this was a new thing for me, and I had to play this tortured character who was surviving rape, so there was a lot of crazy stuff in there all at once.

Innocent Masuku, who played Bobo, says Yizo Yizo’s success boils down to the fact that Gibson and his team were so willing to take risks with their casting decisions. Most of these risks payed off, but there were some that didn’t work out too well (more on that later). Masuku says:

Yizo Yizo is just one of the classics, and it’s as simple as that ekasi. And I think part of that goes back to the freedom that we had on set. As actors we were given quite a bit of freedom and we were able to add a lot of input into the script, sometimes even changing the flow of entire scenes, and I think the investment of everybody on that show, during filming, just cut through all the bullshit.

But for Gibson and Matshoba the product of a gritty, gripping TV show did not come without some hairy moments. ‘This one time Mavis Khanye gave me a lift to Leeuwkop prison’s juvenile section where they were shooting the prison sequence. I got there and some young inmates who were probably from my township started screaming my name. I told Mavis to take me back home,’ recalls Matshoba. Gibson relates some hair-raising moments:

Ronnie Nyakale virtually strangled Teboho when he auditioned for the part of Papa Action. Working with Ronnie was always a lively experience. In this one scene he continually used the word ‘motherfucker’ or something. We would tell him that he better do it again without ‘motherfucker’, and then he would get back into character and do the scene again – and he would say ‘motherfucker’ again. This happened many times over. He couldn’t do the scene without saying, ‘motherfucker’. Eventually we just had to fix it in the edit. The bash at the end of episode five in season one, when things fall apart after the departure of the principal, felt as wild during filming as it looked on screen. The crew were at the end of their tether and at the end of that night, I felt like I had been through a war.

And it wasn’t just on set that things began to go awry. There was a widespread public outcry and calls to can the show after parents started complaining that the series was corrupting their kids (if only they could see the kind of things that they post on their Tumblr accounts now, they would never stop throwing up). At one point the former Minister of Arts and Culture, Lulu Xingwana, called for the show to be taken off the airwaves, during a sitting of the House of Assembly. Imagine that; parliament debating over a TV show. All of this is remembered vividly by Christopher Kubheka, who played Gunman. The public uproar and criticism from public officials created a pressure that eventually took its toll on everyone.

‘For me, playing Gunman on the show was a lot easier than being away from set,’ he says. He hits a slight pause as if travelling through time to unearth some long forgotten chunks of memory that he left behind, takes a small breath, and continues. ‘The reality is that a lot of people didn’t understand what we were doing. We were vilified and attacked even while others were praising us. I love what I do, but there were moments where I felt like, “Fuck this, I don’t want this acting thing to ruin my life, because of some of the public’s reaction”.’ The show, whose modest genesis was a wall of ideas in a dingy and obscure basement, was captivating the interest of small screen lovers and TV critics alike. Part of the show’s enormity lies in the genius of its creators to get out of the way and let the custodians of the narrative get on with the business of telling a story the best way they saw fit.

The two years between Yizo Yizo season one and two were a much needed reprieve for everyone involved in the series. The audiences that had initially been shocked had become somewhat forgetful of the debauchery of the first season. They were beginning to move on, expecting that the likes of Angus and Teboho would come back with more prim and proper stories in tune with the accord of the times. Instead, what transpired was nothing short of a national ambush. The guys at The Bomb could not resist the urge to further pursue the dark themes the first season had grappled with.

A quick survey of some of the letters sent by angry readers to the editors of various national newspapers at the time, complaining about the show, reveals one startling fact. No one, not a single person complained that the story was not authentic. Seeing ourselves for what we are was unsettling. Kubheka aka Gunman remembers this:

People, and especially South Africans, are ashamed to see the truth, finish and klaar. Everything is just a secret. People want to hide their crap behind closed doors. And now here was this show on TV and suddenly there was nowhere to hide. Now people had to talk about things. They had to start explaining stuff to their kids and a lot of parents and people in general were just bothered by that. Bothered by accountability.

According to Matshoba however, he understood where the public was coming from. He says that there were moments on the show that he was not completely comfortable with, mostly as a result of his own background.

I was the oldest and probably the most conservative of the writing team, and there were many instances of disagreement. But in the end some of the stuff I wanted censored ended up on the screen because the directors eventually called the shots. The broadcaster and the Film and Publications Board implicitly approved these things. In a nutshell, I was sometimes embarrassed and thought the criticism was justified.

Matshoba would later exit the show after the first two seasons, and he was not part of the team that plotted the third and final part of Yizo Yizo’s rock and roll trilogy.

Another part of Yizo Yizo’s jazz is that from the onset, it was a pioneer in documenting the transition from crime in the 1990s, which was heavily influenced by showmanship, to the more blatantly perverse criminal activities of the 2000s and beyond. And all things considered, for a show so widely accused of being violent, it certainly had a shamefully low body count.

But where images of trouble exist, actual trouble often follows. It seems that even though the series is long over, there has been a decade-long pressure imposed by the actors on themselves and from the public at large for their onscreen characters to exist in real life. There have been a lot of Yizo Yizo cast members who have been accused of rape, robbery and assault. Art was beginning to mirror life, at least for some of these graduates of what at the time was easily seen as a misfit colony; a breeding ground for the talented and the terminally misguided.

‘I was recently in Limpopo and a boy came up to me with a Gunman tattoo and he was still in school, and he tells me that he wants to be like Gunman. That really broke my heart,’ says Kubheka, speaking about the shows enduring influence. Gibson attributes this to a lack of audience awareness about the show and its goals, and says that it was a necessary thing to open up the industry a bit more. ‘I think that there was courage and openness at the public broadcaster in those years. We opened the door to a more naturalist kind of television and there was a lot of good work done in what felt like a supportive television environment.

‘In season three, when the show switched its focus and became more of an inner city story, some of its loyal followers felt hard done by. For two long summers Yizo Yizo had been their turf, the one show that documented township reality in a unique way, and now suddenly shades of blackness were being presented in the urban concrete jungle framework. It felt for some loyal fans of the groundbreaking show like a regression; a return to old habits. Gibson defends the decision, saying that it was a necessary part of pushing Yizo Yizo’s story forward.

I wanted the show to move to the city because the characters we had followed were of school-leaving age, and I have always loved Jo’burg city. We were interested in that moment when you are trying to work out what you can do with your life. Everything seems possible and impossible at the same time. We were also concerned about the emergence of xenophobia. I think some of the audience felt that season three betrayed the original formula, which was about a township school.

I’m inclined to agree with Gibson. In fact, season three wasn’t a regression, if anything it was provocatively ahead of its time. Tshepo Ngwane, who had graduated from discreet understudy to enforcer-in-chief, was the protagonist to watch. His transformation from charming schoolboy to being the ultimate nightmare of secular mothers around the country (gay) has to be one of the most assured and perfectly executed pieces of character development in the history of Mzansi television. All of those who had been watching him in season one and two, shy and unable to hit on the ladies who had disparagingly called him gay, well, the joke was on them. Before his passing Tshepo confessed that although the role was worth it, it definitely dented his street credibility. ‘You get chirped a lot about things like that ekasi. People even now are just not receptive of homosexuality. We tried to open minds but I still feel like that is one of the areas where we failed,’ he said.

In addition to its cinematic accomplishment, Yizo Yizo would have been nothing without the music. The soundtrack that silhouetted those stark images was an essential part of making sure that the series was situated in the cultural moment, and anyone watching it could directly identify the story as being joined at the hip with the kwaito movement.

The second season of the show provided the emotional blueprint and sonic taste for the next three years. When you look at the roster of musicians who directly benefitted from having their songs on the show, it reads like a who’s who of underground hip hop, afro pop and alternative kwaito. Many young South Africans first heard the likes of Simphiwe Dana calling down fire with Zandisile on the soundtrack for season three. Or, who could forget the vibrating angst that framed Zola’s rude boy lyrics as he talked about bromance, sex, and block parties on the eponymous Ghetto Fabulous?

Speaking about the role of music on the show, Matshoba notes that it was about creating a reference that would always be on people’s minds. Through the music, the show was able to stay with the audience long after the credits had rolled. Matshoba elaborates:

Well, music is the foremost expression of social mood and era. Kwaito music was emerging as a breakaway from conventional township sounds like, say mbaqanga or marabi. It was a poetry of dysfunction with neither specific nor profound message, more or less a South African version of Pink Floyd’s We Don’t Need No Education. So it suited our subject very well as it was also contemporary.

Kwaito is often referenced by Americans as a South African version of hip hop. And in many ways (except musical ones) this is true. The kind of influence kwaito had on South African style, language and culture is mirrored by the influence that hip hop had on America from the 1990s and beyond. Yizo Yizo rode the wave of that influence in its search for notoriety and immediate visibility. Ghetto Ruff, which was then a thriving indie label, was tasked with compiling the show’s soundtrack. They did not just pull the latest chart hit or reinvent formulas from what was then kwaito’s ongoing past. Instead they took obscure musicians, like Ndrebele Civilization, and genre custodians like the hip hop outfit Skwatta Kamp, and set them side by side with more established voices like the untouchable Amu, the underrated O’da Meesta and the infamous, self-confessed groupie-turned star Ishmael.

What resulted was a soundtrack that was as fragmented as our national conscious but was effective nonetheless. The show’s soundtrack travelled by word of mouth and on radio, and people taped it, sharing it via cassettes. Little known entities like Kyllex and Slovas, although one hit wonders, can today still claim a small green patch in the history of South African music.

Lance Stehr, who is founder of Ghetto Ruff, was one of the masterminds behind selecting and making the tracks for the album. Speaking about this process, he remembers that it was important to include tracks that were relevant to the story.

We were very fortunate to meet The Bomb team around the time when the first series of Yizo Yizo was being shot. They were very interested in meeting around the possibility of doing the soundtrack. At that time Skeem, O’da Meesta, Amu, Kyllex, Ishmael and Ashaan were happening. What was great was that the first single, Yizo Yizo ft Kyllex and Mavusana from O’da Meesta, really captured the feel of the show. Before the second series was broadcast we already had the instrumental of Ghetto Fabulous done. I had asked the producers to send the full cast down to the studio to see whether there was someone who could maybe rap. Fortunately Zola had been cast as Papa Action, and with his dreads cut off Zola looked the part of the gangster rapper, and he pulled off Ghetto Fabulous with aplomb. The rest is SA music history. Lyrically it set the scene. Musically it had that haunting gangster house sound that was anthemic at the time.

Although the story has been criticised for not giving women a voice, the show’s soundtrack was considerably more representative and diverse, giving more female musicians the chance to shine, at times in unlikely spaces. Of all the show’s theme tracks, the great Brenda ‘Mabrr’ Fassie’s afro-feminist rendition of Yizo Yizo must be the standout joint. At once a cry for help and a call to arms, it is full of enthralling echoes and layered vocals about wanting to make ends meet. Deeply haunting, it was the last kick of a career filled with highs; the crest before the wave hit the shore and started rolling back.

Thembi Seete was one of the contributors to the soundtrack for the second season. The pop diva, known for wearing all black leather, possessing a somewhat husky voice and often relegated to the role of side-kick or understudy to the extremely talented, over the top, late Lebo Mathosa, got her big solo singing break on the show. Her track Sure Ntombazana, featuring Wanda Baloyi, was the lead single and a surprising kwaito-tinged call for sisterly unity. Speaking about the genesis of the song, Seete says she remembers feeling frustrated by the lack of sexy female voices in the kwaito genre at the time. ‘Kwaito was present but it just wasn’t sexy like that. I’ve always been a team player, and at the time and even now there weren’t any female-only collaborations happening. So I decided to do the track and it just struck a chord with not only the women but people in general,’ she says. The song was such a hit that is spawned Seete’s full solo debut album Lollipop, a record that was a joint venture with The Bomb Productions.

And what of Yizo Yizo now? Surely a post-democratic South Africa provided plenty of rich narrative for one more season? A kind of tying up of loose ends? Although there is definitely rich subject matter and the necessary distance to reflect on those characters effectively, not everyone seems to agree that we need another Yizo Yizo, least of all Gibson. Notwithstanding, there has been talk over the years about a possible season four, but much of it has been urban legend. Gibson is certainly not keen on the idea of going at it one more time, explaining:

There has always been talk of doing Yizo Yizo 4 but I don’t want to do another one. I love the series as it exists. I want to do new things. We are doing a show called Isibaya at the moment which explores the tensions between traditional and contemporary values in South Africa. I am also developing Hotel Kalifornia – a near future Johannesburg love story-cum gladiator narrative, which confronts the growing disparity between the privileged and the underclass in our world. I feel lucky to have grown up in a society where I have been able to witness such dramatic change. History unfolding at high speed. South Africa, in its ugly beautiful way, is always interesting. Often wondrous and often heartbreaking.

Although it seems almost certain that, barring a scramble for ratings by the SABC, we will never see another season of Yizo Yizo, the show and its legacy (that dirty word) is still without equal. Yizo Yizo was meant to be cathartic; an exorcism of social demons via the medium of television. Instead, through its irreverent upfront narrative, Yizo Yizo captured the early labour pains that come with freedom. It was not just a TV series, it was a symptom. An early smoke signal. Watching the programme with the benefit of hindsight, you are able to pinpoint exactly where we begun our descent.

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags BlackBird Books Book excerpts Book extracts Born To Kwaito Esinako Ndabeni Jacana Media Kwaito Music Sihle Mthembu Yizo Yizo