‘Your birth mother didn’t want you.’ Read an excerpt from Sacrificed, Chanette Paul’s US debut

More about the book!

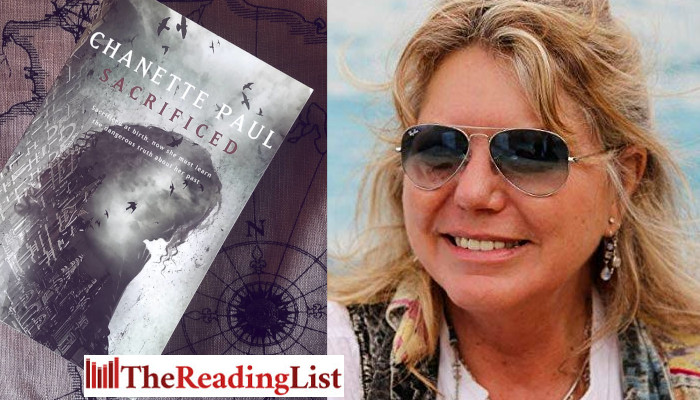

Catalyst Press has shared an excerpt from Chanette Paul’s novel Sacrificed.

Paul is a prolific Afrikaans author, and has written 41 bestselling crime, thriller and romance novels. Her work has been translated into English and Dutch.

Catalyst Press published Paul’s United States debut Sacrificed in 2017. The novel originally appeared in Afrikaans from LAPA Publishers as Offerlam and was translated to English by Elsa Silke.

About the book

Caz Colijn receives a phone call from Belgium that tears her out of her reclusive life. In Belgium, where she tries to trace her and her daughter’s family origins, it becomes clear that that country’s colonial past has had as much impact on her life as the apartheid years in South Africa did.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Prologue

17 January 1961

Katanga, Congo

The night air reeked of savanna dust, sweat and fear. Of betrayal, greed and the thirst for power. A stench Ammie knew well.

César’s left hand gripped her arm. The right hand was clenched around her jaw.

‘Watch, bitch,’ he hissed in her ear. ‘Watch!’

Elijah stood under an acacia, a hare in the headlights. It was new moon. At the fringes of the pale smudge between somewhere and nowhere loomed the vague shapes of more trees. Somewhere to the left something rustled in the tall grass. A jackal howled in the distance, its mate echoing the mournful cry.

A command rang out, followed by the distinct sound of four rifles being cocked. She wanted to close her eyes but she kept staring as if her eyelids were starched.

Elijah coughed and spat out a gob of bloody mucus. Hisvest, once white, was smeared with soil, sweat, saliva, blood. One shoe was missing. He wasn’t looking at the soldiers with their rifles. From behind the lopsided spectacles on his battered face his eyes searched out her own. The glare on the lenses made it impossible to read the expression in his eyes.

Another command. Rifles raised to shoulders.

Sweat rolled down Elijah’s temples. He strained against the ropes, tried to find some slack around his wrists and ankles but finally gave up. His knees twitched. His calves trembled. His lips were fixed in a stiff grimace.

Everything seemed surreal—what she was witnessing now, as well as the events of earlier that evening.

On her way to Elijah’s house to warn him, she had seen the column of smoke from a distance. When she arrived at what had been his house it was clear that nothing had escaped the inferno. Not his desk, with all his documents, nor the shelves with the books he valued so highly. Not the photograph, taken in better days, of Elijah and Patrice Lumumba laughing together. Not even his Immatriculation certificate, the one piece of paper that, only a year ago, had been worth more than gold to every évolué: the passport to a better life.When a vehicle had pulled up beside her and she was dragged inside, none of the spectators feasting their eyes on the mayhem had lifted a finger to help her.

Now, in these moments before the inevitable took place, Elijah stopped being the eternal student, the teacher, the philosopher. He was no longer Patrice Lumumba’s friend, mentor and critic. Or the man who had helped feed, clothe and educate so many orphaned children. No longer the optimist who would simply face the odds and keep going.

He was just a man in a soiled vest, his spectacles tilted at an odd angle. A man who knew too much. Who had too much influence on Lumumba. Who had become a complication. But more than anything, he was the man who loved her.Another command. The words failed to get through to her, but the intention behind them was unmistakable.

The vice-like grip around her arm and chin tightened.

Did Elijah, at that moment, still believe in God’s will? The will of a God who had saved Abraham when he had been on the point of offering his son, but had not granted his own Son the same salvation? Nor Elijah today.

The sound of gunshots shattered the stillness of the night. Ammie screamed as if it were unexpected. And maybe it had been. Maybe she didn’t really believe that these white savages, that César, could be so debased.

Elijah’s body jerked, spun to the right, fell against a tree trunk and collapsed in a heap in the shallow grave he’d probably had to dig himself earlier that day. Flesh, sinew and bone serving no further purpose. Blood pumping through the heart one last time coloured the vest crimson, hiding the smears of dust and saliva.

César shoved her aside. Pain shot through her knee and elbow as she fell on the gravelly earth, grass blades scratching her arms. César wiped his hands on his trousers as if they were contaminated. For a moment his pale blue eyes met hers before a stream of saliva shot from his mouth and splattered against her cheek.

Dimly she became aware of the sounds of Elijah’s body being covered with clods and rocks and gravel. For a brief moment her world tilted.

‘Elijah!’ More than a scream, it was a raw sound from a place she hadn’t known existed.

The first boot struck her side. The second, her shoulder.

‘Whore!’

Somewhere an owl was calling its mate.

The next kick exploded against her temple.

The pool of light grew dim, giving way to the mysterious sounds of nocturnal Africa.

One

Monday, September 1, Present day

Caz

Overberg, South Africa

Tieneke’s voice was as clear as if she were calling from the neighbouring smallholding, instead of six thousand kilometres away. The words got stuck somewhere in Caz’s ear, their meaning distorted by some tube or bone or anvil. Tieneke? After so many years?

‘I said: Mother is at her last gasp,’ her sister repeated when Caz failed to react. Tieneke was impatient, even in this situation.

Caz remembered that about her. Though she had actually forgotten.

‘I didn’t know Mother was still alive,’ she finally found her voice. ‘She must be well into her nineties.’

‘Ninety-eight. She’s been relatively healthy and quite lucid for her age until just a few days ago, when she suddenly went downhill. But she won’t hear of a nursing home. Not that I’d consider it. I’ve been taking care of her for most of her life, after all. Why not see it through to the end?’ Reproach lay like thick sediment in Tieneke’s tone.

With unseeing eyes Caz stared at the splotch the Cape robin had left on the corner of the desk. Bloody cheek, eating Catya’s pellets, and then shitting all over the house.

What could she say to Tieneke? I’m sorry to hear Moth-er is dying at the ripe old age of ninety-eight? I’m sorry you never got married—at sixty-five you’re probably too old now? I’m sorry I didn’t try to make contact again after being chased away like a mangy dog when I needed you most thirty-one years ago?

‘Why are you telling me this, Tieneke?’ The question sounded heartless. Would have been heartless in any other circumstances. Probably still was.

‘Mother wants to see you before she dies.’

Everything fell silent—the sound of the wind in the wild olive tree, the din of birds, the soft hum of the computer—as if she had been robbed of her hearing in one fell swoop.

‘What?’ The word flew from her mouth.

‘We don’t have much time. You’ll have to get a Schengen. Go to the Belgian Consulate. I presume you have a passport. You have to buy your plane ticket before applying for the visa. You probably don’t want to waste your time in Dubai or Istanbul, so forget about Emirates or the Turkish airline, even if they do fly to Brussels. KLM has a direct flight to Amsterdam and from there you can take the train to Ghent-Dampoort. It takes about three hours. You’ll have to change trains at Antwerp Central. From Ghent-Dampoort you take bus number three. Get off at …’

‘Tieneke!’ The sharpness in her voice stemmed the flood. Caz drew a deep breath, tried to calm down. ‘Why does Ma Fien want to see me?’

A deep sigh came down the line. It began in Ghent, travelled through Belgium, across half of Europe, down the length of Northern Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa, and found its way to the cottage at the foot of the Kleineberg in the Over-berg district.

‘I don’t know. She won’t say. She gets terribly upset if I mention the possibility that you might not come. Is that how you want Mother to meet her Maker? So unfulfilled?’

Why should I give a damn about Josefien Colijn’s lack of fulfilment, Caz was tempted to ask. After all, Fien didn’t give a damn three decades ago when she turned her back on her month-old granddaughter along with Caz and sent them out into the world to face scorn and humiliation. But this Tieneke knew. She had been there.

The jacarandas had been blossoming in Pretoria. Also the one in front of her childhood home, where she turned for one last beseeching look at the two women on the porch. Stunned that her mother and sister could send her away like that, refusing even to hear her side of the story. Not allowing her to cross the threshold of the house where she had grown up.

The two of them just stood there. Floral dresses stretched tight over plump figures. Tieneke with the first signs of gray in her wispy blonde hair. Fien’s hair snowy white, stiffly permed. Longish faces, pale blue eyes, lips pursed over yellow teeth sprouting haphazardly from both sets of gums—a legacy of cruel genes.

Lilah had whimpered in her arms. And just then a jacaranda blossom had floated down and settled on the dark hair. That was how she got her new name: Lila, which later became Lilah when her modelling career took off. Hentie had wanted to call his daughter Johanna Jacomina, after his paternal grandmother, but Hentie’s father had forbidden him to have the baby registered. Just as well.

‘Cassie, please.’ These were possibly the hardest two words Tieneke had ever spoken in her life. The image of the women on the porch faded.

‘Please what? Why now? Not once in the eleven years before you returned to Belgium did either of you call me or try to find out how I was doing. I had to learn from an attorney that you had gone back to Belgium and were living in Ghent. Not a single word after that either. And now you expect me to drop everything and fly over there?’

‘I followed Lilah’s career.’

Anger robbed Caz of breath. For a moment everything grew dim. ‘Is that what this is about? Lilah’s success? Are you after her money?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous. We live comfortably. You know we believe in sobriety.’Sobriety? Make that bloody stinginess. Caz had been eighteen before she could choose her own dress for the first time, a dress that wasn’t a Tieneke hand-me-down. One that didn’t have to be taken in and the hem let out to cater for the difference in weight and height. Caz had been a gangly giant in a family of chubby short-arses.

She took a deep breath. ‘Sorry, Tieneke, no go. Give Ma Fien my best, but I can’t travel halfway around the world just because she’s dying. I may be many things, but I’m not a hypocrite.’

Silence hummed across thousands of kilometres before Tieneke cleared her throat. ‘I think she wants to tell you the truth.’

‘Truth?’ The computer’s screensaver began its little dance. Multicoloured bubbles rolling across the freshly translated text added to the out-of-body feeling that took hold of her. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Come over here and find out, Cassie. Before it’s too late. I was only eleven when you were born. Only Mother can tell you.’

‘Tell me what?’

‘Who your biological parents are.’

‘My what?’

‘Your birth mother didn’t want you, so Mother and Father took pity on you and offered to raise you. That’s all Mother said at the time. It’s all I know. You can contact us through the attorney to tell us when you’ll be arriving. Mr Moerdyk, in case you’ve forgotten. In Pretoria. Good day, Cassie.’The line went dead. The silence was pitch black. Like the spots dancing in front of Caz’s eyes.

Ammie

Leuven, Belgium

Eighty isn’t all that old, she wanted to say to Lieve, but what would be the use? For the past few years Lieve had been treating her as if her demise was nigh.

‘You’re eighty-two, Miss Ammie,’ Lieve reminded her.Did she say it out loud? That eighty isn’t old? Why did she say it anyway? Think it? Of course it’s old.

Eighty-two? What had happened to the years between eighty and eighty-two? It had to be a conspiracy. Lieve was trying to confuse her.

‘There you go.’ Lieve stood back. ‘Your hair is done.’

Ammie gazed at her reflection in the mirror. She looked more dignified than she felt. Silver hair in a French roll. A spot of rouge on the cheeks. Pale pink lipstick. She bared her teeth to make sure they showed no lipstick smears. They were whiter than the pearls around her neck and perfectly even. The pearls were real, the teeth man-made.

Was that really her?

Lieve handed her a walking stick and helped her to her feet.

Through the window the day looked dreary. It had been a ghastly August. Not at all summery. And September had fared no better so far.

The rain had been so different in Elisabethville. Pouring from the warm sky and splashing on the warm earth. The weather steaming all through the wet season. The winters were a relief, not something to dread, like they were here in Leuven. Winters without snow, hardly cooler than summer.

Elisabethville. The name had changed. What was it now?

Only yesterday she had remembered it again. That day. She recalled it so clearly. As if it were happening all over again. But she couldn’t remember what. What day was it?

‘Let’s settle you in the living room. I’ll bring you a cup of tea before I start clearing up. Okay?’ Lieve opened the door for her.

Ammie didn’t protest. It was barely an hour since she had got out of bed and she was already tired.

Lieve made her comfortable in a chair before she began to bustle around the bedroom. Ammie closed her eyes.

January 18, 1961

Ammie

Katanga

When Ammie regained consciousness, the first person she saw was a Tetela woman. This was evident from the raised scar tissue decorating her pregnant belly in a complicated labyrinthe design. From this scarification the Tetela people would be able to construe her entire ancestry.

Strange to see a woman in traditional dress. Nowadays every one wore Western clothing. The hand-woven skirt deco rated with cowrie shells sat low on her hips to make room for the distended stomach. The colourful beads around her hips rattled when she moved. Her swollen breasts glistened, the areolas purplish black against the mahogany skin. Her eyes were the colour of lychee pips, their expression inscrutable.

Ammie tried to move, groaned. Her entire body was a matrix of pain.

The woman held a tin mug to Ammie’s swollen lips. She drank gratefully, but with effort. The goat’s milk was cool, yet burned where it touched her cracked lips. It left an herbal aftertaste.

She was lying in a darkened room on a rug made of animal skins. A gap in the wall let in the sun. The filthy panes of the only window were cracked, one corner broken and missing.

Her nose was blocked, forcing her to breathe through her mouth. She could taste rather than smell the stench of sewage and rotting garbage outside. Her eyelids felt swollen and grainy.

‘Elijah?’ she muttered when the worst of her thirst had been quenched.

‘Elijah is dead.’

‘César …’

The woman’s face contorted with hatred. ‘Your husband is gone. The dog ran!’ Her Congo-French was terse and limited. She chased flies from Ammie’s lips. ‘He thinks you dead. Leave you for tai and fisi.’

Ammie recognized the Swahili words, though she didn’t speak the language. In the Congo there was enough work for vultures and hyenas to hear them mentioned quite often. She didn’t speak Lingala either, the Congo’s other lingua franca.

There was a time when she had considered herself a loyal citizen of this country. She might not have been born here, but she had believed it was where her roots lay; it provided her with the only context in which to be herself.

Now she knew she had always been an incomer and would always remain one. She had been as blind as the rest, living in a dream world, where it was considered unnecessary to learn the indigenous languages, get to know the locals, try to understand them. No wonder the Congo had turned its back on them. They were no more than fleas on a dog’s back that had to be brushed off.

‘Where am I?’

‘Elisabethville, but not the one you know. My kitongoji.’ Her voice rang with bitterness.

Ammie could see and smell the difference between her Elisabethville and this woman’s neighbourhood. She could hear it as well. Children shouting and laughing. Drums throbbing in the distance. Women’s voices.

Cité indigène. A city on the outskirts of a city. A city where white people didn’t go. A place to which the indigenous people had to return at night when they had finished their work in the houses and businesses of the whites because they were not welcome in white Elisabethville. At least, that was how it used to be.

‘Why are you helping me?’ Since Independence, white people were the enemy. Before Independence as well, of course, but now it was official.

‘For Elijah. He was good to me. You must sleep now.’

As if the words had magical powers her eyelids grew heavy. The herbs, Ammie realised, before she dozed off.

Ammie

Leuven

‘Oh, Miss Ammie, your tea has gone cold.’ Lieve clicked her tongue.

Lubumbashi. That was the new name for Elisabethville.

Where was Elisabethville again?

Lieve put a crocheted blanket on her lap, tucking it around her knees. ‘I’ll bring you a fresh pot.’

‘That’s kind of you, Lieve. What time will Luc be home from school?’ The wall clock was no longer where it used to be. The room looked strange. Whose house was this?

Lieve stroked her hair. ‘You haven’t seen Luc in years. He’s a professor now. Just like your first husband. You told me yourself.’

No, my second husband. Luc’s father was my second husband. Jacq DeReu. César was the first. And after Jacq came Tobias. Three husbands. One great love. The one I never married. Elijah.

This time she kept her thoughts to herself. The pious Lieve wouldn’t understand. Jacq hadn’t understood either.

‘Luc is no longer in Leuven.’ Lieve’s voice came from far away, as if she was coming to the end of a long tale.

‘Who’s this Luc again?’ Ammie closed her eyes and heard Lieve give a deep sigh.

Caz

Overberg

Damn Tieneke! Spoiled her entire day with her lies. It couldn’t be true, Caz had decided after the initial shock. Tieneke just wanted to trick her into making the journey. That was all it could be.

She was the late-born child of Josefien and Hans Colijn. Born in the HF Verwoerd Moedersbond Hospital on October 2, 1961. Registered as Cassandra Colijn. Raised in Pretoria. First in Rietfontein, as a baby, and later in Meyerspark, where she went to school and was confirmed in the Dopper Church. She had been Cassandra Colijn all her life, except for the eleven months her marriage lasted. How could it change now, after almost fifty-three years?

Caz shoved the wireless mouse aside and rolled her of-fice chair away from her desk, annoyed. She had done hardly anything all morning. What was on the screen was pure drivel. She would have to re-do the lot.

The deadline for the translation was still some time away but it was a bloody brick of a novel. And translating from Afrikaans to English always took longer than the other way round. Moreover, the writer occasionally lapsed into the Cape dialect, which is nearly impossible to translate. Not to mention the many instances of humorous word play that made hardly any sense in English and wasn’t even remotely funny in translation.

Correct language usage was the easy part. The challenges of translation lay elsewhere. How does one translate the voice of an author, for instance? Another person’s take on life? The heart and soul of the disembodied author behind every book?

Word for word and sentence by sentence is how you initially translate. If that fails, you try to find the broader meaning, the author’s intention. You try to get inside his mindset, to do justice to the meaning behind the words, the sentences, the story.

Her own present mindset wasn’t exactly helping the process along.

Of course it wasn’t the complexity of the translation that was paralysing her brain.

Five words kept echoing through her mind, overriding all other words and their semantic and emotive value in any language. Biological parents. Didn’t want you.

There was a mindset for you. Here, take this baby. I don’t want her, for reasons a, b and c. Good luck with raising a child who doesn’t share your gene pool.

Blue eyes. That’s what Caz had in common with the rest of her family, though her eyes were a different blue. Darker, with light brown specks. Her hair was blonde like theirs but, while her mother and sister—or whatever they were to her—had straight, thin hair, and her father had been bald for as long as she could remember, Caz had thick, tightly curled hair. She’d worn it long for most of her life in an attempt to make it more manageable. Now that the blonde had turned to grey it was easier, the curls slightly more relaxed. More corkscrew than frizz.

But what set her apart most from her sister and parents had always been her height. Where they were short and plump, she had shot up as if her shoes had been sprinkled with fertiliser. At thirteen she had already towered over her father. She had always been the tallest in her class, until some of the boys caught up with her in their last school year. Finally at eye level with them, she still couldn’t look them in the eye. Her awkwardness in male company was firmly rooted by then and the conviction that she was big and clumsy was an essential part of the way she viewed herself.When she looked in the mirror she could see her face wasn’t unattractive and her figure was well proportioned, despite her being so tall. Yet she felt unattractive. Undesirable. Different.

Not only was she too tall, she also lacked the right background. There was no Boer general in her family tree, no Afrikaner hero who was a distant relative’s uncle or grandfather. No grandmother who had survived a Boer concentration camp.

Josefien and Hans Colijn had arrived in South Africa in 1951, when Tieneke was a year old. They knew little about the country’s history. It was merely a place where the prospects were better. Where bakeries weren’t as plentiful. Where the Second World War hadn’t hit the population so hard. The same war that had made Hans leave the Netherlands to end up in Belgium, where he’d met Josefien.

To Josefien, South Africa was the back of beyond.

There were a number of Dutch people in Pretoria, Fien was Belgian—so they were different even in their otherness. On top of which they were Protestants, which distinguished her mother from the other Belgians.

Yet it was because of her distinctive looks that Hentie had noticed Caz, as unbelievable as she had found it at the time.He had liked the fact that she was tall. ‘At least I can look you in the eye,’ he’d said the night they met at the agricultural students’ barn dance in Potchefstroom. It wasn’t completely true, of course, since he was still a good ten centimetres taller than Caz.

And Hentie was crazy about her hair. He had raked his fin-gers through her curls that first evening when he kissed her goodbye at her residence. Her very first breath-taking kiss.He found her reticence endearing. Maybe because he mistook it for timidity and failed to perceive the ire it masked.She, on the other hand, had been completely blind to the fact that he was simply searching for the best possible mother for his children. A woman with a strong body and a submissive spirit. One who would accept his father’s whims and moods.

Physically she was indeed a strong young woman. About the rest, he had been sorely mistaken.

Not that he was the only one who had been mistaken. What she hadn’t realised at first was that Hentie and Andries Maritz came as a package. Marry the son and you inherited the father. At Liefenleed, the Maritzes’ farm on the far side of the Soutpansberg, they farmed together as the family had been doing for generations.

All she saw at that stage was a big, strong, handsome farmer. One who had fought in the Border War for what he believed in. A real man’s man. A pure-bred Maritz.

That first evening, and in the months that followed, she would never have guessed that this ‘real man’ was his father’s lapdog. Just as she had never guessed there was a genetic explanation for the difference in appearance between herself and the rest of her family. If, of course, Tieneke wasn’t lying simply to get her to go to Ghent.

Didn’t want you. The words had such a bleak sound.How could a mother put her child in the arms of another and walk away?

Or did she leave her baby in a cradle and hit the road? A rubbish bin? On someone’s doorstep? Did she turn for one last look?

Did she ever wonder about her daughter again? Remember birthdays? Think of her at Christmas? At her coming of age? Did she wonder about her daughter’s wedding day? Whether she had grandchildren? Even great-grandchildren were a possibility, Caz thought, though Lilah had never mentioned such plans.

How could you leave a child and her entire progeny be-hind—blood of your blood?

She would have to find answers to all these questions, Caz realized. Or she would lose her mind.

She pressed her fingers to her temples. No, it just wasn’t possible. Tieneke had to be lying.

Or did it explain everything? Tieneke’s aversion to her for as long as she could remember. Ma Fien … No, apparently not her mother after all. Fien. Fien’s increasing aloofness until that moment when she finally chased Caz away. Her father’s lack of interest in any of his youngest daughter’s exploits. He had been kind, but not interested in his so-called late-born child.

And Lilah, of course. It could explain Lilah.

~~~

Categories Fiction International South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Chanette Paul LAPA LAPA Publishers Sacrificed