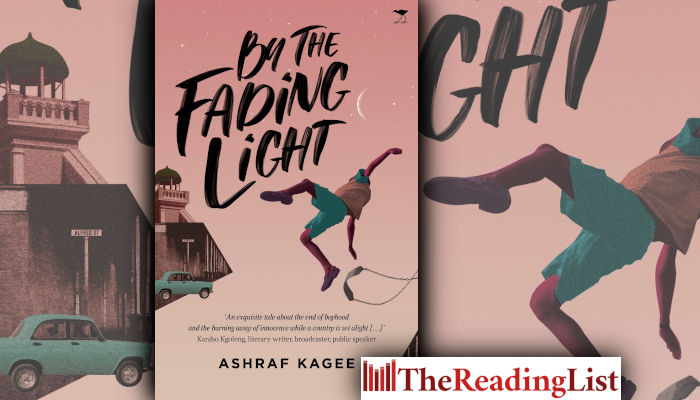

‘We are all refugees of our childhoods’: Read an excerpt from Ashraf Kagee’s dazzling new novel, By the Fading Light

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from By the Fading Light, Ashraf Kagee’s stunning follow-up to the award-winning Khalil’s Journey.

Set in 1960 in Salt River, Cape Town, this exquisitely told novel follows four friends on the cusp of adolescence. A shocking murder sets in motion several discoveries about their world, rendered in delicate detail by the author.

By the Fading Light is a dazzling tale of the loss of innocence, the uncertainty of kinship ties, and the unbending nature of fate.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Prologue

You always tell me I get a faraway look in my eyes when you ask me about my childhood. The truth is, I find it difficult to remember all the details of what happened that summer long ago. But every once in a while the memories come and visit, in dribs and drabs, in flashbacks and feelings, in pictures and poetry, always with sweet sorrow. Today is one of those days. I must confess my memory is not as good as I think it is, even though those days seem like yesterday.

It was an age of innocence. The world was much less complicated than it is now. It was before our country disentangled itself from its colonial masters, before the winds of change swept over our continent, before Lee Harvey fired a bullet at a handsome American president and altered history, when beetles were insects, before youth culture swept the world, before me and my friends discovered girls, before we became men. Before our lives changed.

What happened that summer would influence the course of my life and made me the person I am today. For the longest time afterwards, I couldn’t speak about it to anyone, not even my friends. As the years tumbled across history, the memories faded and then returned. They are sometimes more vivid than ever, sometimes just a blurry shadow, leaving me with a longing to go back and fix things. There are times I wonder if I imagined it all, if all those things happened in a different life that wasn’t mine, but into which I could see. But they were as real as you and me, as real as the time that has slipped away like sand. They were as real as the wistfulness of lost youth. And time, that merciless assassin of dreams, has a way of closing in on you as you make your way down the meandering path of your life.

We are all refugees of our childhoods, sandpapered by the past, fleeing the vulnerability of a different life in a different time. We carry around our memories like piles of dirty laundry, from when we wake in the morning until we sleep at night, hoping that the day’s doings will wash them clean. But of course they don’t. The present is not innocent. It is coloured and moulded by those long-ago days.

But here’s the thing. I find myself wanting to rewrite history, to make all of us young again so that we can do it over, perhaps a little better this time, perhaps without so much pain, perhaps with a few more laughs. Those young boys, those purple-prosed poets of twilight, are with me to this day. I see them still, laughing, carefree, teasing each other, as if the world was their playground. And then? And then, well, then the laughter stops, as we slowly realise what reality has brought. We begin to frown and become perplexed because the heavy work of life has begun. They say life turns on a dime.

I’m writing this now because I haven’t been ready before. That faraway look you see in my eyes? Well, that’s me thinking of what my life could have been. But perhaps the time is finally right.

The year was 1960. A few months after Sharpeville erupted and all those people were killed by the police. We didn’t know much about it then, but I read about it in the history books many years later. We weren’t very political in those days, you see. Nor were our parents. In fact, all we could think about were the films that were playing at the Palace Bioscope or going swimming at Trafalgar Baths. Those were the golden, halycon days of our youth. Until they weren’t.

But let me not get ahead of myself. Let me tell the story from the beginning, for both of our sakes, yours and mine, so that we can all understand how things got to be the way they are.

Chapter One

Amin

If only Amin Gabriels had not taken the long way home that winter’s day in August 1960. If only he’d gone his usual route after leaving his friends when the school day was over, as he did every other evening. But the fact of the matter was that Amin, son of Shaheed and Rukya Gabriels of Fenton Road, Salt River, pupil at the esteemed Cecil Road Primary School, master player of the game of marbles, avid reader of highly coloured comic books, perpetrator of pranks that only jinns in the netherworld could imagine, teller of silly jokes and proud owner of a Mickey Mouse watch that his granny had given him for his 11th birthday, had a good reason for prolonging his walk and delaying his arrival at home. The fact of the matter, quite frankly, was that home was not always an easy place to be.

Just that morning, his parents Rukya and Shaheed had had a shouting match that resulted, yet again, in his father storming out of the house, and his mother burying her head in her hands and wailing as if a red-hot poker was being driven through her heart. Amin knew the routine. It was as predictable as clockwork. His parents would fight – and not just fight, mind you, but engage in the most enraged quarrelling you could imagine, with screaming, shouting, insults, threats, invectives, name-calling, and the uttering of such choice profanities that Amin, if he had not been so distressed at the awfulness of it all, might have kept them for his own personal use with his friends. Following this display, Shaheed would leave the house, slamming the front door with such ferocity that its glass pane would rattle. Rukya, as was her custom, would engage in loud banshee-like wailing – shrill, piercing and uncontrollable – that would make Amin wish he could be lifted by a tidal wave and taken to another place, perhaps a desert island where there were no people, like the one in the Robinson Crusoe film that had played at the Palace Bioscope a few years ago. But no tidal wave arrived and no desert island beckoned. No oasis of tranquillity was available, only the heavy gloom that found its way into every corner of the house.

The final stage of his parents’ battles, and the one that ate deep into Amin’s bones, was the silence, sometimes lasting several days, even a week or more. During this time, his parents would not speak. No one greeted anyone, either at arrival or departure. Dinner was served in silence and eaten grimly. The wireless would not be turned on, except for the news. No visits to family would be made, and Amin and his younger brother and sister would be discouraged from talking, even to each other. The unspoken rule was that silence should be maintained. This state of affairs would persist until suddenly one day Shaheed would say something to Rukya, and then, as if by magic, it would all be over, as if nothing had ever happened. Rukya would reply. Normality would be restored, and life would go on. Dinner conversations became animated. Walks were taken, and Sunday train rides to Simonstown recommenced. Even giggling was tolerated. Until the next time.

But right now, Shaheed and Rukya were in the throes of their cycle. That morning they’d had a blistering argument about money, or rather the lack of it, resulting in Rukya informing her husband in a shrieking tone that she wished he’d never crossed her path, and that if she could reverse time, she’d never have fallen pregnant with any of their children. Storming from the house, his face contorted with rage, Shaheed had retorted that if they didn’t have children, his life would be bliss. No mouths to feed! Amin had set off for school that morning understanding that, had he not existed, his parents would both have been far better off.

The day had gone by slowly and sorrowfully, the events of the morning reverberating in his mind. He anticipated the tension he would have to endure at home later. He could predict with perfect accuracy that his parents would not be speaking to each other and barely to him. Amin understood that his role in the family was to accept blame for the marital rancour that existed between Shaheed and Rukya, even though he’d had nothing to do with this morning’s quarrel, or with any other for that matter.

Amin sat through his classes, answering when asked a question by Mr Hicknekar, performing arithmetic computations, reciting poetry as needed, and saying Christian prayers at the beginning of the day as was required by the school. No matter that he and most of his classmates were Moslem. School rules dictated that everyone say the Lord’s Prayer at the beginning of each school day, in unison and at the tops of their voices. After all, this was Christian National Education, a gift from the ruling National Party whether you liked it or not. No ifs, ands or buts. The only moments of fun came during break, when he and his friends, Ainey, Haroun and Cassius, ran and tumbled in the playground, pretending to shoot each other with makeshift guns and dying from imaginary bullet wounds. His friends were mostly fun, except when he was the victim of a prank or on the receiving end of a joke. The thing that united them against all others – teachers, parents, other children – was the fact that they’d all been born on the same day, June 16, 1949.

When they’d discovered this nugget of information on the very first day of school, it had been a source of immense fascination.

It was only natural that the boys would become as thick as thieves, joined at the hip, brothers in arms forever. This didn’t mean they didn’t fight, or try to outdo each other. But their shared birthdate was the glue that held them together, and they spent most of their free time in each other’s company.

After school that afternoon they’d hung around with their spinning tops, until Cassius’s string had snapped, heralding the end of the day’s games. It was time to go home. Except that home for Amin was not a place that beckoned. It was, on this and many other days, a place to be avoided for as long as possible until, when the light of the day started to fade, he had no option but to return to endure another night of silence and melancholy. It was for this reason that Amin took the long way home after the school bell rang and he said goodbye to his friends. If you could call it goodbye, that is – an upward movement of the chin followed by a perfunctory ‘See you.’

On this winter’s day, as Amin made his way through the convoluted streets of Salt River, as the cold north wind blew and a light drizzle fell on his face, fate had something in store for him. He looked at his Mickey Mouse watch. It was already after five o’clock. The sun would be setting soon.

Earlier that year, in March in fact, the country had been shaken this way and that, up and down, but you wouldn’t have known it in the Salt River community – except for the announcements on the radio and the headlines yelled out by the Argie boys who sold newspapers on street corners. Sixty-nine people shot dead by police in Sharpeville.

Why the police had shot the demonstrators was anyone’s guess. Some said that black people wanted to take over the country, which was just plain silly. It was a matter of fact and common sense that the whites ruled over everyone else, and any idea that black people could or, even worse, should rule could only be pure nonsense. It was surely against the natural order of things. Some said that the people were just standing outside the Sharpeville police station because they were tired of being bossed around by whites. Some said they wanted to be arrested so they could fill the jails. Some said that they weren’t just standing, that they were throwing stones, or might even have been planning to kill the white policemen and take over the police station. In any case, everyone knows you don’t cross a white man, unless you want to get shot, which is exactly what happened to those people in Sharpeville in March.

But the months passed and the news about Sharpeville eventually died down. It wasn’t that life changed, at least not in any noticeable way. Let’s just say that something changed. Something intangible, something that altered the way people looked at each other – especially the way they looked at the police. Something that was felt as far away from Sharpeville as Salt River, where a young boy was taking a circuitous route to delay his arrival at his parents’ home.

As the sun was starting to set, Amin found himself meandering towards Woodstock Beach, a small cove close to Cape Town harbour. The sea pleased him, even a beach as rudimentary as this one, packed haphazardly with dolosse, those concrete blocks with complex shapes that interlocked to form a barrier against the erosive force of the Atlantic. There were moves afoot, he’d heard, to reclaim the land from the ocean. Perhaps it was because so many ships had been coming in recently. Perhaps they needed an extension of the harbour so that the ships had more place to dock.

He liked the wind against his face. He enjoyed the roar of the ocean and the squishiness of the sand under his shoes. He liked the salty smell and the crisp air and the screaming of the seagulls that hovered above. But most of all, he liked the solitude. If he wasn’t with his friends, he preferred to be alone. Grown-ups usually wanted to tell him what to do. They ordered him around whenever they saw him, as if any child who seemed to have nothing to do was in need of instructions, usually barked in an acrimonious tone. The assumption of adults, it seemed to him, was that the youth constantly needed to be reprimanded, regardless of whether they were innocent or guilty of any acts of mischief.

But now, as Amin walked along the windy beach, watching the pale sun depart over the Atlantic, wishing he had somewhere else to go rather than home to his parents, someone was approaching. A man.

‘Nogal cold today, isn’t it?’ the man said, pausing. It seemed he wanted to make conversation.

Amin returned a blank look. He did not particularly feel like speaking, especially to a stranger. His mind was elsewhere. What if his father actually hit his mother in a moment of rage? What then? What would he do? He, Amin, all of eleven years old.

‘Quite cold, hey?’ the man said again, now walking alongside him.

Amin ignored him, walking on.

‘Hey!’ the man said, jerking his head towards him. ‘Don’t you know how to talk to big people?’

Amin gave him another blank stare. ‘Huh? Don’t you know?’ The man took a step in Amin’s direction, his voice rising sharply.

What in the world did he want? Amin walked faster, trying to get away from this stranger who seemed angered by the sight of him. It didn’t help that he was unusual looking, hairy with a thick bull-neck.

‘You think you’re clever?’ the man snapped. And now, for goodness sakes, the man was grabbing at his shoulder.

The fear Amin felt was visceral and primal and ran through his body from top to bottom. All thoughts of his parents evaporated as his mind focused on the matter at hand, namely the need to get away from this man. The hold on his shoulder was painful. Amin twisted away, loosening the grip, and broke into a run. He was now afraid, terrified quite frankly, as the man seemed determined to apprehend him, for reasons he truly could not fathom.

Amin felt hands grip his shoulders again. Hairy arms that smelled of sweat wrapped around his neck and twisted him around. He kicked and struggled, trying to scream. But now fingers were closing around his windpipe. Amin grabbed the man’s wrists, kicked out, his legs flailing madly, desperately. He felt his knee sink into the softness of the man’s groin. The man yelled out in pain and rage, but still Amin felt his rough hands around his throat. He gasped and choked and kicked and flailed, but his movements became weaker and more feeble. Time seemed to slow down and his vision blurred. He could feel his body becoming limp, sagging under its own weight.

And then he wasn’t afraid anymore. He no longer feared for anything, least of all the man with the thick neck and strangely high voice. He was no longer concerned about his home, or his parents, or their marriage, or their conflicts, or his mother’s wailing, or his father’s temper tantrums, or their screaming matches, or the hateful silences between his parents, or the tension of wondering when the next bout of rage would commence, or guilt at being blamed for their marital troubles, or the anxiety or the fear or the apprehension or the unease or any of the awful feelings that he associated with home. He felt no pain, but could feel his eyelids fluttering.

As his eyes rolled up he saw, fleetingly, the dolosse scattered on the sand. It was funny – they looked like children’s jacks that had been sprinkled on the beach by some giant god who wanted to keep the Atlantic in check. Knucklebones. That was it. The girls played this game at school … concrete jacks to keep the ocean at bay. Strange, the kinds of things you attend to under such circumstances, he thought to himself.

He was outside his body now. He gazed down at himself, pitying the helpless boy who lay there gasping, at the mercy of his murderer. The horror of it was over. The terror was gone. He was detached, letting go, watching almost with fascination as a sense of peace came over him. It was not that he particularly liked the man’s hands around his throat, but he no longer felt a need to resist, or to kick and flail and scream. His legs had stopped moving, then his arms, then his eyes fluttered some more … and then they didn’t. His body went limp. He gasped for air one last time.

And then, as the sun disappeared into the Atlantic, as if it were ashamed that it could not come to his rescue, Amin Gabriels – son of Shaheed and Rukya, pupil at the esteemed Cecil Road Primary School, expert player of marbles, avid reader of comic books, perpetrator of pranks of all sorts, teller of jokes as feeble as a wet paper bag – exhaled for the last time, and his body became still.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Ashraf Kagee Book excerpts Book extracts By the Fading Light Jacana Media