‘To be great is to be misunderstood’ – Read an excerpt from Dare Not Linger, the sequel to Long Walk To Freedom

More about the book!

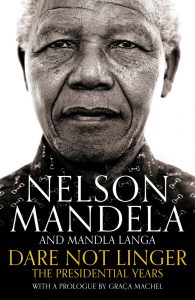

Read an excerpt from Dare Not Linger, the story of Nelson Mandela’s presidential years, drawing heavily on the memoir he began to write as he prepared to finish his term of office but was unable to finish.

Acclaimed South African writer Mandla Langa has completed the task, using Mandela’s unfinished draft, detailed notes that Mandela made as events were unfolding and a wealth of unseen archive material.

With a prologue by Mandela’s widow, Graça Machel, the result is a vivid and often inspirational account of Mandela’s presidency and the creation of a new democracy. It tells the extraordinary story of a country in transition and the challenges Mandela faced as he strove to make his vision for a liberated South Africa a reality.

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from Chapter 1 of the book, shared by Pan Macmillan:

***

CHAPTER ONE

The Challenge of Freedom

Nelson Mandela had heard this freedom song and its many variations long before his release from Victor Verster Prison in 1990. The concerted efforts of the state security apparatus and the prison authorities to isolate him from the unfolding drama of struggle – and its evocative soundtrack – could not stop the flow of information between the prized prisoner and his many interlocutors. The influx into prisons, including Robben Island, in the late 1980s of newcomers who were mainly young people from various political formations – preceded in 1976 by the flood of student activists following the upheavals in Soweto and elsewhere – marked the escalation of the struggle and brought with it new songs, each verse a coded commentary on progress or setback, tragedy or comedy, unfolding on the streets. The recurring refrain of the songs was that the South African regime was on the wrong side of history.

Like most people who accept that history has carved for them a special place, and probably being familiar with Emerson’s mordant dictum – ‘to be great is to be misunderstood’ – Mandela knew that his own legacy depended on the course he had championed: the talks between the government and the ANC. These had started five years prior to his release, when fresh from a check-up at Volks Hospital where he was visited by Kobie Coetsee, the minister of justice, Mandela had broached the question of talks between the ANC and the government. Coetsee’s presence was a glimmer of hope in an otherwise unrelieved darkness. The year 1985 marked the bloodiest period of the struggle, a time characterised by an irreversibility of intent and a hardening of attitudes among the warring sides that stared at each other from across a great gulf.

Oliver Tambo, the ANC president and Mandela’s compatriot, had just called on South Africans to render the country ungovernable. Mandela, however, realised that the toll would be heavier on the unarmed masses facing an enemy using the panoply of state power. But he was a prisoner, a political prisoner, who, like a prisoner of war, has only one obligation – and that is to escape. Only, his escape from his immediate confinement was irreversibly intertwined with the need for the broader escape, or liberation, of the people of South Africa from the shackles of an unjust order. Having long studied his enemy and having read up on its literature on history, jurisprudence, philosophy, language and culture, Mandela had come to the understanding that white people were fated to discover that they were as damaged by racism as were black people. The system based on lies that had given them a false sense of superiority would prove poisonous to them and to future generations, rendering them unsuited to the larger world.

Separated from his prison comrades on his return from hospital to Pollsmoor Prison, a period Mandela called his ‘splendid isolation’, it was brought home to him that something had to give. He concluded that ‘it simply did not make sense for both sides to lose thousands if not millions of lives in a conflict that was unnecessary’. It was time to talk.

Conscious of the repercussions of his actions to the liberation struggle in general and the ANC in particular, he was resigned to his fate: if things went awry, he reasoned, the ANC could still save face by ascribing his actions to the erratic frolic of an isolated individual, not its representative.

‘Great men make history,’ CLR James, the influential Afro-Trinidadian historian writes, ‘but only such history as it is possible for them to make. Their freedom of achievement is limited by the necessities of their environment.’

In almost three decades of incarceration, Mandela had devoted time to analysing the country he was destined to lead. In those moments of waiting for word from his captors or for a clandestine signal from his compatriots, he mulled over the nature of society, its saints and its monsters. Although in prison – his freedom of achievement limited by the necessities of his environment – he gradually gained access to the highest councils of apartheid power, finally meeting with an ailing President PW Botha, and later his successor, FW de Klerk.

Outside, deaths multiplied and death squads thrived; more funerals gave rise to more cycles of killings and assassinations, including of academics. A new language evolved on the streets, and people became inured to self-defence units and grislier methods of execution, such as the brutal ‘necklace’, being used on those seen as apartheid collaborators.

In all the meetings Mandela held with government representatives what was paramount in his mind was a solution to the South African tragedy. From De Klerk down to the nineteen-year-old policeman clad in body armour, trying to push away angry crowds, these were men and women of flesh and blood, who, like a child playing with a hand grenade, seemed unaware of the fact that they were careening towards destruction – and taking countless millions down with them.

Mandela hoped that sense would prevail before it was too late. Nearing seventy, he was aware of his own mortality. Perhaps it was in a whimsical mood that he wrote, much later, what amounted to a prophecy:

‘Men and women all over the world, right down the centuries, come and go. Some leave nothing behind, not even their names. It would seem that they never existed at all. Others do leave something behind: the haunting memory of the evil deeds they committed against other human beings; the abuse of power by a tiny white minority against a black majority of Africans, Coloureds and Indians, the denial of basic human rights to that majority, rabid racism in all spheres of life, detention without trial, torture, brutal assaults inside and outside prison, the breaking up of families, forcing people into exile, underground and throwing them into prisons for long periods.’

Like almost all black South Africans, Mandela either had first-hand experience of each violation he cited, or knew of people close to him who had suffered hideously in the hands of the authorities. This was the period of sudden death, where the incidents were reminiscent of titles of B-grade American movies: The Gugulethu Seven. The Cradock Four. The Trojan Horse Massacre. In all of these instances, where young community leaders and activists were killed brutally at the height of state clampdowns in the mid-1980s, the state security agencies either denied complicity or claimed to have been under attack.

Remembering Sharpeville and other massacres perpetrated by the apartheid security forces where scores of people had been maimed or killed through police action, Mandela evokes disturbing images of a ‘trigger-happy police force that massacred thousands of innocent and defenceless people’, and which blasphemes, using ‘the name of God … to justify the commission of evil against the majority. In their daily lives these men and women, whose regime committed these unparalleled atrocities, wore expensive outfits and went regularly to church. In actual fact, they represented everything for which the devil stood. Notwithstanding all their claims to be a community of devout worshippers, their policies were denounced by almost the entire civilised world as a crime against humanity. They were suspended from the United Nations and from a host of other world and regional organisations … [and] became the polecats of the world.’

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 was an international story that almost overshadowed a major domestic development that had occurred a month earlier. On 15 October 1989, Walter Sisulu was released from prison together with Raymond Mhlaba, Wilton Mkwayi, Oscar Mpetha, Ahmed Kathrada, Andrew Mlangeni and Elias Motsoaledi. Five of them, alongside Mandela, had been among the ten accused in the Rivonia Trial of 1963–4, and were his closest comrades. Jafta Kgalabi Masemola, co-founder with Robert Sobukwe of the PAC, was also released. Six months later, Masemola died in a car crash, which some PAC members still regard as suspicious.

Mandela had prevailed on the authorities to release the men in Pollsmoor and on Robben Island as a demonstration of good intent. The negotiations for their release had started with Mandela and Botha, and had stalled when, according to Niël Barnard, former head of the National Intelligence Service (NIS), due to ‘strong antagonisms in the SSC [State Security Council] these plans [to release Sisulu in March 1989] were put on the back burner’. The release left Mandela with mixed emotions: elation at the freeing of his compatriots and sadness at his own solitude. But he knew that his turn was coming in a few months.

Kathrada recalled how the last time ‘prisoner Kathrada’ saw ‘prisoner Mandela’ was at Victor Verster Prison on 10 October 1989, when he and other comrades had visited Mandela in the house where he was held for the final fourteen months of his imprisonment.

Mandela said to the group, ‘Chaps, this is goodbye,’ and Kathrada et al. said they’d ‘believe it when it happens’. Mandela insisted that he had just been with two cabinet ministers who assured him that his comrades would be freed. That evening, they were given supper in the Victor Verster Prison dining hall instead of being returned to Pollsmoor. And then, just in time for the evening news, a television was brought in and an announcement was made that President F. W. de Klerk had decided to release the eight prisoners: Kathrada, Sisulu, Mhlaba, Mlangeni, Motsoaledi, Mkwayi, Mpetha and Masemola.

The men were returned to Pollsmoor Prison and three days later they were transferred. Kathrada, Sisulu, Mlangeni, Motsoaledi, Mkwayi and Masemola were flown to Johannesburg where they were held at Johannesburg Prison. Mhlaba went to his home town of Port Elizabeth, and Mpetha, who was from Cape Town, remained at Groote Schuur Hospital where he had been held under armed guard while being treated. Then, on the night of Saturday, 14 October, the commanding officer of Johannesburg Prison approached the prisoners and said, ‘We’ve just received a fax from prison headquarters that you are going to be released tomorrow.’

‘What’s a fax?’ Kathrada asked. He had then been in prison for over twenty-six years.

On 2 February 1990, FW de Klerk stood up in Parliament and announced the unbanning of the ANC, the PAC, the South African Communist Party (SACP) and about thirty other outlawed political organisations. He further announced the release of political prisoners jailed for non-violent offences, the suspension of capital punishment and the abrogation of myriad proscriptions under the State of Emergency. For many South Africans who had writhed under the jackboot of apartheid rule, this was the proverbial first day of the rest of their lives.

Categories International Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Dare Not Linger Long Walk to Freedom Mandla Langa Nelson Mandela Pan Macmillan SA