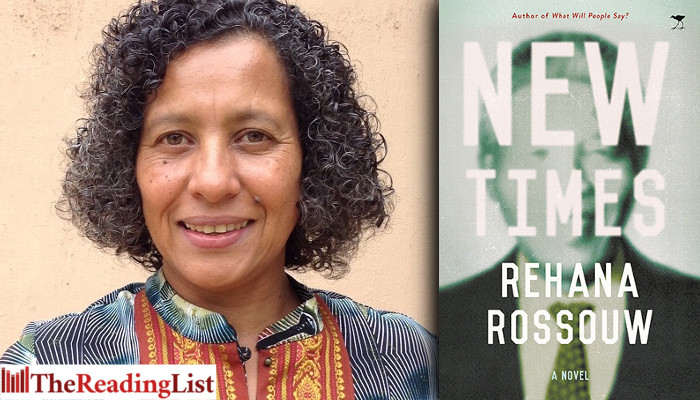

Read an excerpt from New Times, the new novel from award-winning author Rehana Rossouw

Courtesy of Jacana Media, read an excerpt from New Times, the much-anticipated new novel from Rehana Rossouw.

Rossouw is the acclaimed and award-winning author of What Will People Say?

Her new novel takes us into a world seemingly filled with promise yet bedeviled by shadows from the past. In this astonishing tour de force Rossouw illuminates the tensions inherent in these new times.

Read the excerpt, from Chapter 2 of the book:

Lizo roars out of the Parliamentary precinct and heads out of the centre of town and up the hill to Bo-Kaap, his deep-tread tyres churning through the puddles in the streets. He turns to me when we’re brought to a halt at a red traffic light. ‘What about the Minister of Welfare? Made any progress on that story since we spoke last week?’

Lizo’s only dropped a story into my lap like this once before, and he must know plenty that’s a guaranteed front-page lead. I had just started out as a journalist when I met him. He’s from the Eastern Cape, near Lusikisiki, didn’t know Cape Town at all when he arrived eight years ago fresh off Robben Island. I was his chauffeur, driving him to meetings with the leadership of the Mass Democratic Movement where they planned the next defiant strike against the apartheid government. Then he told me the message from Madiba, gave me an international scoop in my ninth month as a reporter.

It was hard at first, knowing so much about the insurgency long before my competition caught a whiff. Then I got the hang of it: everything was off the record when I tagged along with Lizo but could be stored away for future reference. The only advantage his friendship gives me is that my stories have a depth of understanding other journalists can’t match. I can analyse the strategies, and identify faults when required, no matter how much Lizo protests. He does not control what I write, never has. So why is he tipping me off now? Is he supporting me or is this his next strategic move?

Still, I couldn’t resist, jumped onto the corruption story with a passion that I had worried I had lost to unemployment. I describe how Coen stuttered when I called last week to ask what action the party was taking against the Welfare Minister. I say nothing about the resistance from Milly and Joy when I pitched the story, although the thought of it sends a furious shiver rumbling down my spine. Lizo doesn’t need to know; I can deal with it. ‘I will have it tied up in a few days. Just waiting for a couple of responses.’

‘That’s not good enough, Ali. This story is going to break, and soon. Surely you can see this one is bigger than anything else you’re working on?’

No shit, of course I can see that a Cabinet Minister being investigated for corruption is a huge scoop. ‘I’m working on it, okay? Why’s it so important I get the story into the next edition? What’s it to you?’ We’ve arrived at my house, halfway up steep Upper Leeuwen Street lined with a row of semi-detached, iron-roofed houses. Lizo turns to face me after he parks and switches off the ignition, sliding his arm across the steering wheel, trying his best to look casual while his voice climbs into the freezer. ‘Don’t you want this story, Ali? There are other journalists I could give it to.’

Now I know for sure Lizo’s playing me, he’s driving his finger deep into another sore pressure point. Of course I want this story, I have a reputation to resurrect, but first I want to know what I’m getting into. What am I missing? It was his idea that I ask the Minister of Welfare’s party if they are going to ask him to resign. Is he stirring up a controversy to divert attention from something else? It’s too dark in the cab to make out his expression but I can smell hot conspiracy oozing from Lizo’s pores. The rusty cogs of my brain finally squeal into life. ‘It’s the President’s budget vote, isn’t it? This is the first time Madiba’s going to face questions in the House since Winnie resigned from the Cabinet. You’re looking to sidetrack everyone.’

Poor Madiba, I really feel for him. The thick glass that separated the world’s most famous husband and wife during their rare visits on Robben Island masked the jagged rift growing between them as the long years went by. He tried hard to be a good husband when he was released; gave Winnie an important role in the Movement. But he was forced to fire and divorce her when her bitter letters to her young lover were published in newspapers around the world. He tried again when he appointed his Cabinet; recognised her contribution and her huge constituency by making her a Deputy Minister. Winnie squandered money on bodyguards, accepted the gift of a house from a diamond smuggler and was sued in court for hiring a Lear jet and refusing to pay, forcing him to fire her again. My heart bleeds for Madiba but I’m not sure if it’s a pinprick or a severed artery – there are some misfits and deadbeats from the previous regime in his Cabinet and people with very dubious struggle credentials.

I can feel Lizo’s pretend nonchalance in his shrug. ‘Believe what you want, Ali, this story is true and it’s yours if you want it. But you’ve got to work fast; it’s going to break soon. Let’s go inside, the neighbours are going to wonder what we’re up to, parked outside like this.’

The smell of food drifts across the damp breeze into the cab as I open the door, slides onto my saliva glands and sends them springing up in a happy dance. Lizo snaps his fingers impatiently as he waits on the narrow stoep while I dig around in my backpack for house keys. We follow our noses past the lounge, down the passage to the kitchen where the windows are steamed up with the fragrance of curry.

I walk in ahead of Lizo and hurry to the stove, hug my grandmother around her broad waist and lean my chin on her shoulder to bring my nose closer to the food simmering in the pot. ‘Laikom Big Mummy, that smells so lekker! Don’t be surprised if the neighbours come knocking on our door tonight.’

She puts the lid on the pot, swings around and pushes me aside. ‘Is he here?’ Her smile strains towards her ears when she spots Lizo in the doorway and her slanted eyes scrunch into laughing Buddha slits. Her smile disappears as she lifts her apron over her head and returns bright as a light bulb under her big red doek. ‘There’s my boy,’ she sings her greeting. ‘Come, sit down Lizo, it’s good to see you.’

He ignores the instruction and walks over to greet her with a kiss on each rosy cheek, a quick but thorough examination of her face and a formal, ‘Laikom, how are you Auntie Ragmat?’

She smiles and stretches up on her toes to give him a loving pat on his cheek. ‘Surviving. I’ve seen worse days. It’s good to see you my boy, why you stay away so long? How are you doing?’

The mutual admiration society in the kitchen doesn’t notice when I leave. In my bedroom I take off my shirt, sniff the armpits and hang it in my wardrobe. I can get one more wear out of it before it needs a wash. I change into flannel pyjama pants and a long-sleeved black sweater, ditch my Doc Martens for fluffy slippers.

The bedroom next to mine is in darkness. I leave the light off, tiptoe to one of the two beds, sit down and gently shake the small shape curled under the duvet. ‘Laikom Mummy, are you awake? Lizo’s here, you haven’t seen him for a long time. Big Mummy cooked special for him, come join us in the kitchen.’

The duvet’s pulled tight over her head, there’s no response. I prise her fingers free and slowly lift the duvet, pull it down the black scarf, over curls of black hair escaping onto her forehead, past eyes shut tight, pale cheeks, clenched lips, to skinny arms clutching her waist. ‘It’s Lizo, Mummy. Get yourself ready and come visit with us.’ I switch on the light as I leave the bedroom.

In the kitchen Big Mummy and Lizo are seated at the table with a bowl of samoosas between them. He looks happy as can be, but she’s staring at him with a hangdog look. ‘I know mince samoosas are your favourite, Lizo. But I thought just this once, why not try the potato? What do you think?’

Is she out of her mind? There’s no need to discuss our situation with Lizo; we are going to make it and at the end of the month I’ll be back on my feet. We don’t need his help. Just four more weeks of tinned fish, soup, dhal and spaghetti then we’ll eat beef samoosas again. There’s nothing wrong with Big Mummy’s potato samoosas, she’s generous with the dhania and black mustard seeds and besides, the original samoosa first made in Calcutta was filled with potato. Few people in India eat beef mince the way the Indians do in Cape Town. There’s no need to apologise for nothing.Lizo’s reply is strangled by the hot potato filling bouncing on his tongue. ‘Auntie Ragmat, this is … seriously … delicious. It’s good to be home again.’

I take a seat and stretch out my arm but it’s too short to reach the bowl. ‘Can I have a samoosa, kanala?’

Big Mummy ignores me and passes the bowl to Lizo. ‘Have another one my boy.’ After he takes one she shelters the bowl under her generous breasts, curving her arms around it protectively.

I wave my hand in her direction. ‘Hello, I’m also here. I did say kanala.’

She takes one small samoosa out of the bowl, hands it to me and checks if her special guest is ready for his next one. Eight years ago, Big Mummy fed Lizo his first decent meal in more than a decade. When he cried into his plate of beans curry and roti, she took him into her heart. A few days after I started out as a reporter, The Democrat’s editor Ashraf Behardien sent me to the harbour to collect a prisoner being released from Robben Island. Ashraf had undertaken to do the task, but his mother-in-law died and he was needed at home. He had just promoted me and hired a new personal assistant – I owed him big time. Lizo Mkhize came down the prison ferry gangplank looking like a Malawian policeman in his khaki suit and brown leather shoes, carrying an apple carton filled with his belongings. I didn’t know what to do with him so I took him home.

When Big Mummy discovered who had been Lizo’s cellmate for ten years, she welcomed him into the family. She is related, either by blood or marriage, to at least half of Bo-Kaap. Imam Hoosain, who had been the oldest political prisoner on Robben Island, was married to her cousin Adeela from the Bryant Street Slamdiens. My grandmother supported Adeela through the trial that convicted her husband of terrorism and went to all the family weddings and kiefaits that he was prohibited from attending. Most of the neighbourhood regards Lizo as a member of my family, there are a few who have problems with his dark skin and peppercorn hair.

Big Mummy allows me a second samoosa; it looks like there are ten more in the bowl for Lizo. They’re deep in conversation with eyes for no one else until Mummy walks into the kitchen and we all look up. Her white kurta is creased to hell and gone but she’s fixed her scarf, there isn’t a strand of hair in sight.

Lizo’s greeting sounds wrapped in cotton wool. ‘Laikom Amira, nice to see you again.’ I look away from the smile wobbling on his lips while Mummy examines every last pore on his dark chocolate face, every last hair on his new beard; it’s a private smile, not meant for me. Lizo’s almost always serious with me; what he’s got going with Mummy is special. It’s hard to describe because it is mostly silent, like they go to a peaceful place where no one else can follow.

Mummy’s voice is a hoarse whisper, could be this is the first time she’s used it today. ‘Laikom Lizo, it’s good to see you again.’

I pass the bowl with the last samoosa to Mummy. She eats only enough to keep her flesh attached to her bones, needs only enough energy to walk the four hundred metres from our house to the mosque up the street. She praises Allah every waking minute of every day but gives very little to everyone else. When I came home last December and told her I had lost my job, all I got was a sad hand on my shoulder and a murmur of Arabic as she took the problem to Allah.

Sure enough, Big Mummy made beans curry and roti. I don’t complain because it’s also my favourite. She puts the serving bowl in front of Lizo; in this house of women, the men dish first. (It’s a rule everyone in Bo-Kaap lives by even though no one can explain it.) We all stare as he tears off a piece of roti, scoops up meat and soft sugar beans soaked in thick sauce, snorts softly as he lifts his hand to his mouth.

Mummy dishes two small spoons of food and tears off half a roti. Her loud ‘biesmillah’ brings Lizo’s hand that’s halfway between his plate and his mouth to a halt. He lifts his shoulders and his eyebrows. ‘Sorry Amira, biesmillah.’

I dish food onto my place and pass the bowl to Big Mummy just as Lizo’s ready for his second helping. She refills it at the stove and hands it over; men go first, she can wait. Lizo keeps his head down while he shovels food in, doesn’t notice that we’re saving all of the little meat in the curry for him alone.

I lean back in my chair after I’ve had enough, lick the last taste of curry from my fingers. The kitchen is warm with friendship; it hasn’t been this relaxed in a while. In the 1980s many walls in Bo-Kaap homes had framed copies of Desiderata, it was the in thing back then. I can’t remember all the words but it was along the lines of going placidly in the haste and there being peace in silence. It’s like that when Lizo comes home to us.

Categories Fiction South Africa