Read an excerpt from Butterfly: From Refugee to Olympian, Yusra Mardini’s story of rescue, hope and triumph

More about the book!

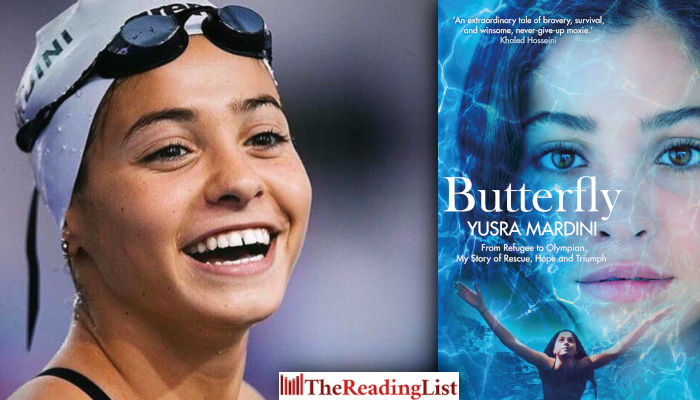

Pan Macmillan has shared an excerpt from the extraordinary new novel by Yusra Mardini – Butterfly: From Refugee to Olympian, My Story of Rescue, Hope and Triumph.

Mardini fled her native Syria to the Turkish coast in 2015 and boarded a small dinghy full of refugees bound for Greece. When the small and overcrowded boat’s engine cut out, it began to sink. Yusra, her sister and two others took to the water, pushing the boat for three and a half hours in open water until they eventually landed on Lesbos, saving the lives of the passengers aboard.

Butterfly is the story of that remarkable woman, whose journey started in a war-torn suburb of Damascus and took her through Europe to Berlin and from there to the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

Read an excerpt:

Mum pushes Shahed gently forwards. The little girl looks up at us with her big, blue eyes.

‘Take your sister with you when you go out,’ says Mum.

Sara and I wander out into the rain, Shahed trotting along beside us. In Malki, we run into some old swimming friends. They tell us about another swimmer who has been killed in a bomb attack somewhere in the north. We sit around, listless. The war, the deaths, the mortars. It’s all become so normal. I think back to the shock of leaving Daraya. It seems like it happened to a different girl, another Yusra. Now, if I hear shelling, I hold my breath for five seconds and then get on with whatever I’m doing. I only notice it when the guns stop firing. When the jets stop flying overhead.

By the summer, all anyone can talk about in the cafes in Malki is the latest disappearances among our friends. I sit with my school friends Hadeel and Alaa, making lists of people who’ve left. Some of them we never see again. Others pop up a few weeks later in Germany, Belgium, Sweden, France. The details are always vague. It’s never quite clear how they get there.

In early autumn, one of Sara’s best friends, Hala, manages to get to Germany on a student visa. She writes to Sara telling her she’s in Hanover. Hala says Germany is a good place to study. Sara is fascinated by the idea. Hanover. Germany. A good place to study. A good place for a future.

‘I’m leaving,’ says Sara one night at dinner.

I roll my eyes. She’s been talking about nothing else for months. She shoots me a look.

‘What?’ she says. ‘Really. I’m going to Germany.’

‘What does your Dad say?’ says Mum.

‘All my friends are leaving,’ says Sara. ‘Mum, I have to go.’

I look down at my plate and wonder what would happen if Sara really did leave and go to Europe. Would I go with her? Would I want to? I’m not at all sure. Leaving Syria seems like a very big step.

‘Your father is the one who can afford to send you,’ Mum is saying to Sara. ‘You know it’s up to him.’

Sara sighs. She has already spoken to Dad about leaving, but he tells her to wait and see what happens. She can’t go without his approval. He’s the one who will pay for the journey. The idea is put on hold. Sara goes back to dreaming of Hanover and scheming her escape.

One Thursday night in early October, I meet swimming friends from the national team out in Malki. They’re excited, fresh from the World Cup in Dubai, where they won a bronze medal in the 200m freestyle relay. As we talk, one of my old team mates shows me a photo of the medal ceremony. I gaze at the smiling, proud faces, the shining medals around their necks. My eyes well up with tears. For the first time, I see what I threw away. The loss hits me like a punch to the gut. All the passion, all the determination, all the ambition rushes back at once. I get to my feet. There’s no time to lose. I have to get back into the pool. A shudder of excitement runs down my spine. I hurry home to tell Mum and Sara my decision. I want to start training again. Mum sighs.

‘But it’s dangerous at the pool,’ she says.

‘It’s not as bad as it was,’ I say. ‘I’m willing to risk it. I can’t sit around here my whole life. I want to do something.’

‘What’s the point?’ says Sara. ‘You’re too old now anyway. It’s not worth it. There’s no future in it.’

I scowl at my sister and give Mum a pleading look. She shrugs and says I should speak to Dad. I call him up the next day and tell him I’m going back to training. I’m hoping he, of all people, will be behind me. He is less supportive than I’d hoped.

‘If you want to swim, I understand that,’ says Dad. ‘But don’t expect any help from me. You left alone, you can go back alone.’

I hang up. I’m not disappointed, I’m more determined than ever. I’ll go back, I’ll swim, I’ll get good, and I’ll be back on top. With or without my family behind me. This time, no one will be forcing me. It’ll be entirely my choice. I’ll choose to swim.

Some of the coaches raise their eyebrows when I turn up at training the following week. But no one says anything. I’m just back. The break of almost a year has taken a huge toll on my speed. All the cute little girls in the group are faster than me. I accept it as a challenge. I stop going out with friends. Every night, I train for two hours after school. After that, I go to the gym for another hour. On the way home from every session, I remind myself what swimming means. I can sacrifice all the teenage fun now. There’ll be plenty of time for that when I’m thirty, when I’m done with my swimming career. Some nights I come home blue in the face from training so hard. I eat and go straight to sleep. Mum looks worried and tells me not to overdo it. But there’s no way I’m giving up now. I have to get back up to the level I was at before I stopped. Sara is no help either.

That March, I turn seventeen. Sara books an entire restaurant for my birthday. Maybe she’s trying to persuade me to stop swimming and enjoy life again, or maybe she feels bad for not supporting me. Either way, we have an incredible time. Leen comes over to our house with her box of tricks and we dress up like film stars for the occasion, just like old times. Mum frowns as I totter out into the road in the highest heels I’ve ever worn. I wave at her cheerfully and set off down the hill. Men stare at us all the way to the restaurant. One guy looks like he’s about to fall over as we walk past. We laugh and dance and celebrate. The war has never seemed so far away. I didn’t know it then, but it was to be one of our last big nights out in Damascus.

Life goes on. Training, school, training. I try to keep my head down, get through my last two years of school, but the war is always there to disrupt and distract me. Some nights, electricity outages plunge whole swathes of the city into long hours of darkness. In places, power is rationed to just four to six hours a day. Some Damascenes get around the blackouts using big car batteries, or, if they can afford to run it, a diesel generator. We adjust until the outages, too, become a part of daily life.

Death is random and ever present. It falls from the sky in the street, in midday traffic, without warning, then we dust ourselves off and carry on. In the spring, the attacks in Baramkeh around the Tishreen stadium start up again. The area is full of targets. The university, the state news agency, hospitals, schools, the stadium itself. Mum is beside herself with worry. A few nights every week, she calls me on my way to the pool. The conversation is always the same.

‘Come back home,’ she says.

‘Why?’ I say. ‘I’m going to swim.’

‘Just shut up and come back,’ she says. ‘Right now.’

I hurry home to find Mum waiting for me with news of more mortar or rocket attacks. I know she wants to protect me, but deep down we both know I’m no longer safe anywhere in the city. I could just as easily be killed in the pool as outside on the street or at home in my bed. We know a lot of people who die at home. A fire, a bomb, or just a stray bit of shrapnel.

Often I hear the mortars falling around Tishreen once I’m already training. One evening I’m in the pool, pushing myself as hard as I can. My face is burning against the cool water. I battle the urge to stop and rest. Another length, another whirl and scoop, just a few more metres. I reach out and grab the end of the pool, rest for a few seconds. My shoulders jerk up towards my ears in alarm as a splitting crash thunders around the pool. There’s a moment of silence. Then the swimmers spring into action, screaming and shouting as they splash over each other to reach the sides.

‘Out! Everybody out,’ shouts the coach, urgently waving his arms towards the exit.

There’s no time to register what’s happening. My mind is blank as I haul myself out of the water. Crowds of swimmers push past me, shivering with shock and panic as they hurry towards the doors. I reach the exit and turn back. I look up to the ceiling and spot a ragged hole in the roof showing a tiny speck of open sky. I look down at the water below. There, shimmering on the bottom of the pool, is a metre-long, thin, green object with a conical bulb thinning down to a point at one end. It’s an unexploded RPG. A rocket-propelled grenade. I stare at the bomb, unable to tear my eyes away. Somehow, it had ploughed through the roof and landed in the water without exploding. A few metres in either direction and it would have hit the tiles, killing everyone within a ten-metre radius. It takes a few seconds to sink in. I’m lucky to be alive. Again.

Author image: Facebook/Composite: The Reading List

Categories International Non-fiction

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Butterfly Pan Macmillan SA Yusra Mardini