‘I think I might have killed someone’ – read an excerpt from Nicky Greenwall’s debut thriller A Short Life

More about the book!

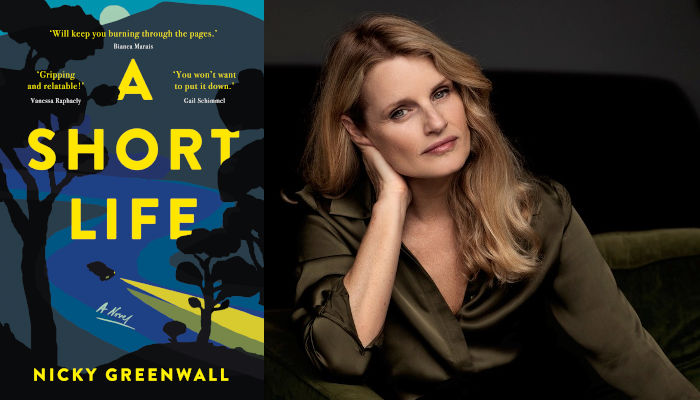

Penguin Random House SA has shared an excerpt from A Short Life, the debut novel by Nicky Greenwall!

‘Gripping and relatable!’ – Vanessa Raphaely

‘You won’t want to put it down.’ – Gail Schimmel

Greenwall is a is a well-known producer, entertainment journalist and former TV presenter best known for the hit television shows The Showbiz Report, The Close Up, Screentime and more recently, the multi award-nominated documentary series The Beautiful People.

As a print journalist, she has contributed to Elle, Marie Claire, Men’s Health, Glamour, Good Taste and the Sunday Times. Greenwall has conducted one-on-one interviews with a host of Hollywood stars including Leonardo DiCaprio, Matt Damon, Jim Carrey, Idris Elba, Charlize Theron, Emma Thompson, Johnny Depp, Angelina Jolie, Naomi Campbell, Hugh Grant and Sir Anthony Hopkins, to name a few. She lives in Cape Town.

About the book

‘What are you thinking about?’

‘I think I might have killed someone …’

How far would you go to protect the ones you love?

Two car accidents take place on the same night, on the same stretch of twisting valley road. One is fatal, and six friends’ lives will never be the same. Only two of them know what really happened that night – and one will stop at nothing to get to the truth.

When your life is on the line, who can you really trust?

Read an excerpt:

~~~

FRIDAY

23:55

Franky

Constantia Nek Road

A RED-RIMMED MOON IS our searchlight. From my vantage point, the car reminds me of a scarab that has landed on its back. Unlike the creature of my imagination, this car doesn’t struggle to right itself. It has resigned to the inevitable. It lies where the foot of the forest meets the bottom of a steep verge – motionless except for a faint plume of smoke curling from beneath the body.

Nocturnal insects throb. The South Easter moves through the poplars and the blue gums above. Clouds shift. Every so often there’s a passing car, not slowing down. Twin red lights disappear quickly behind the curve of the mountain. I know it’s too dark to see much at that speed, unless you’re looking for something at the side of the road – like we were.

‘He can’t be in there,’ says Nick, cutting the engine. My free hand opens the passenger door. Nick’s movements mirror mine. The Jeep’s doors slam shut with a synchronised thud. I make my way behind the Jeep towards my mother’s parked Mercedes. She was here first – called at my request. Her burgundy relic is parked on the shoulder: a painted fingernail marking the spot. As I reach for her passenger door, I turn back to see Nick sliding down the incline towards the wreckage. Moonlight picks out the silver in his hair as he manoeuvres past the roots and rocks. He will be disappointed to get his shoes dirty. I feel certain I hear a siren up ahead, but it could be the wind, or a peacock.

‘Jesus,’ my mother says, reaching over to release the bygone mechanism of her passenger door. Her windows are the kind that wind down by hand.

‘How long have you been here?’ I say, sinking into the wrinkled hide of her passenger seat. Her hand is cold and papery.

‘About five minutes. I left as soon as you called—’

‘Mom, I’m sorry to involve you. I—’

‘I can’t go and look. I thought I could but … I can’t.’

I take in my mother’s outfit: cardigan over her pyjamas, gardening shoes still caked in mud.

‘I think we should call the police,’ I say.

‘I’ve just done that.’ Tilt of the chin, flick of grey-gold fringe communicate I’m not an idiot, you know. She wraps her cardigan tighter around herself.

‘I shouldn’t have called you, Mom. I’m sorry, I thought—’

‘He called you, didn’t he? He must be all right.’ Her eyes are their deepest hue when she’s worried, inexplicably paler when she’s angry. Before I’m able to make the distinction, the car’s interior lights fade to black, as if marking the end of a scene.

‘Where are the police?’ she says.

I am all but silent, grinding a thumbnail between my teeth. My husband will know what to do. My mother’s soliloquy continues: ‘Why didn’t he call his wife first?’ I strain my ears to listen for the sirens I was sure I could hear before. ‘Surely she—’ She’s building up for a lecture, as certain of her opinion as one should be after sixty, but her words dissolve in the air as our eardrums accept the sound of a car starting, wheels moving at speed. The Jeep, Nick’s car, is skidding forwards into the darkness, already gone.

‘Where on earth is he going?’ she says, flicking her brights, illuminating nothing.

‘Mom!’ My voice escapes my throat at an odd angle. The sirens are real now. I can hear them, can imagine their blue-and-red glow. ‘We need to go, Mom.’

‘Shouldn’t we—’

‘Just go!’ She turns the key and slams her mud-caked foot on the accelerator. The wheels make a grinding sound as we leave the soil of the verge for the smoothness of the road.

~~~

FRIDAY

14:32

Sebastian

Table View

THE IMAGE IN FRONT OF me is a visual platitude – a postcard. Blue-grey, flat-topped mountain, flanked by twin peaks, all blanketed in a thin tablecloth of cloud. This is not Cape Town. I should be looking directly up at the mountain, or down from it, or sideways at it. It should fill the frame. I’m too far north for comfort. Charley leans against the heat of her car, on her phone as always.

‘Come the fuck on, Seb,’ she says, looking up. ‘We have to be there in an hour and we still have to check the light.’

The sea air wends its way into my nostrils as I ready myself for our usual argument. Time. We are always bickering about how much we have left. Time is money, as they say.

‘I need to see it’s there.’ I retrieve the crumpled square of paper from my pocket, check the code again.

‘It’s there. They sent me a picture. I forwarded it to you.’

‘That’s not a picture. That’s an artist’s impression.’

A sigh. ‘Get on with it, but be quick.’

I press the code, hear the requisite beep beep beep and watch the metal curtain rise.

‘Happy now?’

I pull back the dust cover. Happy doesn’t quite equal the feelings rippling through me. I can hardly believe I have been trusted with this gleaming piece of luxury machinery, shipped from Germany under cover of darkness. Its surface feels alive. I can see my reflection distorted. I look older than I feel. I should shave.

This car, and how I will capture it, is my ticket. Think sweeping, majestic aerials, tightly crafted close-ups, shimmering night shots lit with giant sun lamps. We’re spending the budget. In less than a week, this car – which no one but a handful of execs and I have seen – will be gliding along the contours of Table Mountain, a tattooed hero at the wheel. He will circumnavigate beaches, forests and vineyards – an imperfect circle – before returning to where he started. Crisp white titles on a black screen will read, ‘Besitze die Straße … Lebe die Reise … Fahren Sie den Moment.’ Own the road. Live the journey. Drive the moment. The car is finally here. Now all I need is my leading man.

I close the door to the storage unit and return to our air-conditioned cocoon. Charley likes to drive. I don’t mind being driven; it gives me the opportunity to think about my angles, work out some of the technical aspects of next week’s shoot.

I close one eye, make L shapes with my hands and watch the scene unfold through my side window, pretending this is new. Charley is thinking her own thoughts.

As we reach the city centre, mountain looming above us, ocean now behind, I’m reminded why so many commercials and films are shot in my home town. Cape Town is a stand-in, an understudy, and, unlike the rest of the world this time of year, the light is always on.

The suburbs of Cape Town are beads on a string – a necklace hanging from the slopes. The city centre – spiky, gleaming reflective surfaces – that’s the clasp. Crop out the mountain, it could be New York. Pan in closer, central London.

We move south along the coast through the streets of Green Point, the wide mouth of the stadium and Sea Point where waves crash against the rusted railings of the promenade. Palm trees cast geometric shadows on apartment blocks. A cubist impression of Cannes or Los Angeles.

At the foot of Lion’s Head, we slide through Bantry Bay and Clifton – four perfect pearlescent replicas of remote islands. Clifton gives way to Camps Bay. Neon signs face the not-yet-setting sun as they would on Miami’s South Beach or Santa Monica Boulevard. Buildings give way to pure mountain rock. The Twelve Apostles hunch over the Atlantic. Ocean to the right, rock to the left. If it were nighttime, this would be where we’d flick on the brights.

Hundreds of car commercials have been shot on this stretch. You’ve probably seen one – you just didn’t know it was this road. It could be Monaco, or the Algarve. Road closures are a bitch, and permits are a nightmare but, in fairness, someone needs to pay for the gabion cages and steel nets to stop rocks from tumbling onto the road.

The smooth tarmac leads to my neighbourhood, Llandudno: clapboard houses and glass compounds jut out at angles towards the glare of the ocean. It’s Malibu, without the celebrities, and no key is needed to access the beach.

We pass the turn-off to our house, down Suikerbossie, the steep hill that has become the source of more than a few of my speeding fines. We dip into the valley. The light changes, as does the mood. My attention is drawn to the vastness of Chapman’s Peak – the unreal colour of the sea – and then, as though it’s the first time I’ve seen them, I marvel at the silver shacks of Imizamo Yethu. Thousands of makeshift houses stretch up as far as you can see and gravity will allow. Electricity cables weave between washing lines; giant satellite dishes balance on every zinc roof: eyeless alien life forms on a dystopian lunar colony.

We snake past the township. The trees begin to thicken. It starts to drizzle. The road gets very winding here and signs suggest we take the bends slowly. Hout Bay is the Borneo jungle, or the Amazon rainforest. Our car climbs higher up the back of the mountain. At Constantia Nek, a traffic circle sits like a cameo on the décolletage. If we were so inclined we could park at the foot of the mountain, take a hike up its slopes, or veer slightly to the right and choose one of two roads that lead down into the exclusive valley suburbs of Bishopscourt or Constantia.

‘Let’s go through Constantia,’ I say.

Charley’s hands slide smoothly over the steering wheel. The mountain is now on our left. A perfect patchwork of vineyards stretches down towards the False Bay to our right. It is Napa County or the Hollywood Hills. The Constantia Wine Route is one of the oldest parts of Cape Town, as evidenced by the 200-year-old trees lining the roads. I draw breath as we pass the driveways of English-country-style houses in cul-de-sacs whose names evoke summer smells: Avenue Provence, Rose Way, Meadow Lane, Alphen Drive.

Trees become traffic lights – or robots, a fact I’ve had to explain to more than a few of our foreign clients. The lights are red. A one-legged man approaches Charley’s open window displaying a toothless smile and a cardboard box of ripe fruit. Charley’s finger curls around the button to close the window. I see her suppress a smile as he shouts through the glass, ‘Where the lady goes the mangos!’ The lights turn green. Now we’re on the M3, meandering towards Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and the fortress-like, ivy-covered facade of the University of Cape Town. The clouds are heavy in the sky. The windscreen wipers increase their metronomic sweeps. Moments later, the greenery on the slopes gives way to burnt trees (evidence of recent fire) and dry grass (evidence of recent drought). Frame out the highway and it’s an African wilderness complete with mountain zebras and wildebeest. I take it all in through the streaks of rain on my window. The sky becomes still, clouds thin.

The dry peak of the mountain towers above Hospital Bend, a curved ribbon of highway that hugs the building where the first successful human-to-human heart transplant was performed. Now known as Nelson Mandela Boulevard, the road brings us seamlessly into the industrial district: Salt River, followed by Woodstock. Ad agencies, factories and just-built micro student accommodation. We’re back at the clasp of the necklace, skyscrapers reflecting the last rays of afternoon sun. The journey has taken us through two separate weather conditions in less than an hour.

Now, how to tell it in thirty seconds?

THE CASTING STUDIO ON THE outskirts of town is a tiny, air-conditioned space that makes my eyes feel dry. Anxious models and actors sit in orange plastic chairs, unsticking and re-sticking numbered labels to their chests. Been there. Done that.

‘Number fifty-five!’ yells our casting director. In the decade we’ve known Angus, his beard has gone from slate to silver, but his Metallica Tour t-shirt has held up remarkably well. Charley has been nodding off the whole afternoon. I worry about her lack of sleep; it’s worse than it was after our kids were born. That first time, after Katie’s arrival, Charley didn’t sleep for four days straight. Her teeth chattered, hands shaking as she caressed her face, marvelling at the strange woman in the mirror. She told me she felt that if she slept, Katie might die. She knew it was illogical, but some primal force told her rest was not as essential as our daughter’s survival. Eventually, I had to hold Charley’s head firmly on her pillow with the flat of my palm, promising I would watch over them both, until the shaking subsided and she disappeared into sleep.

When Leo arrived two years later, she let him curl in between us in our bed, until she became convinced one of us might suffocate him if we turned over in our sleep. Leo was inconsolable, as if picking up on his mother’s intrusive thoughts. In the dead of night Charley would pace the hallways. I would find her asleep on couches and stairs and rugs. She told me she needed to stay awake, like a hammerhead shark.

This time, four years later, she tells me she can’t understand the purpose of her wakefulness. Charley doesn’t do anything without good reason. She’s even started taking the CBD oil her mother sent her. Deirdre swears by any new-fangled, New-Age potion to make you feel and look better. Sometimes Charley thinks her mother (who is pushing seventy) looks better than she does. I told her it’s because she is single and no longer has children under the age of seven. She raised her eyebrows and that was the end of that conversation.

Today I am wearing my new spectacles, the red-framed ones. Charley is the only person who knows I don’t need them. She knows I want to be the sort of director who wears red-framed glasses, slightly too small for my face. She thinks it makes me look just the right side of eccentric. Not quite Pedro Almodóvar, but close enough.

Charley walks back into the studio from the toilet. I have one of the arms of the spectacles in my mouth and I’m squinting at a laptop, nodding my head furiously. I am agreeing with The German Client who is, at this moment, patched in from Hamburg. While he talks, my mind can’t help but regard his existence, this man in his glass cube, snow falling dramatically down floor-to- ceiling windows, as we parade a digital conveyor belt of tanned, tattooed specimens for his consideration.

‘What do we think of this guy?’ I whisper to Charley. We are behind a two-way mirror. I’ve learnt the hard way, the space is not completely sound-proofed. She looks up at the model, who smiles broadly at the camera as if his life depends on it.

‘Hey! I’m Keith, I’m twenty-seven!’ he says.

‘He’s a bit young,’ she mouths, gesturing to her biceps, ‘and not enough tattoos.’ Charley has always been decisive. It’s one of the many qualities I love about her.

Keith is now brandishing a disembodied steering wheel. He grins like a child wielding the controls of a bumper car. His tattoos are subtle. I have more ink on my arms, I note with pride. I’m not the right age group, though. The German Client wants young.

‘Do you have a licence?’ says Angus.

‘I do, sir. And a motorcycle licence too.’

‘And have you done any competitive car commercials?’ ‘No, sir!’

‘Right. Thanks, Keith. We’ll be in touch.’

BY 5 P.M., EIGHT MEN HAVE come and gone through the confines of the thin casting-studio walls, narrowed down from 135 the week before. The German Client has his heart set on a Brazilian whose right arm boasted an impressive seascape sleeve, the waves undulating gently as he contracted the muscles in his bicep. ‘It sends the right message,’ says The German Client.

I nod and nod as is customary. Charley yawns, opens and shuts her eyes, windscreen-wipering her corneas to clear the sleep that threatens to overtake. And then she shakes herself into consciousness before she says, ‘We’ll need a release form.’

‘All sorted,’ confirms Angus, unhitching the camera from its tripod.

‘For the tattoo?’ says Charley, straightening the lapels of her blue blazer, re-arranging her new haircut, reminding him who is in charge, who is paying for everything.

‘I’m sorry?”’ he says. The skin around Angus’s eyes crinkles in confusion.

‘The tattoo artist needs to sign off on us using the tattoo in the commercial. It’s his artwork. He could sue us if we don’t have the proper permissions.’ And then, because she can’t help herself, ‘I thought this would have been obvious?’

Angus searches his teeth with his tongue.

That’s my wife – always a stickler for the details. But, while I smile inwardly with pride, I chew on the arms of my useless red frames. If the client doesn’t get his first choice for leading man, will that make him less likely to acquiesce to my creative whims?

‘You’re joking,’ says The German Client through the speakers of the laptop. ‘I am not,’ says Charley, matching his tone.

Angus is already on the phone to the Brazilian’s agent. The German Client is put on hold, the laptop closed while Angus whispers that the Brazilian was inked when he was drunk. He thinks he was in Belgium but can’t remember the name of the tattoo parlour. He thinks it may have closed down.

‘Brilliant!’ I say. ‘No chance of us being sued then.’

‘Seb,’ cuts in Charley, her eyes connecting with mine. ‘We can’t take a chance. Remember what happened last time?’

I feel the tips of my ears redden. The beer commercial in the art gallery. How could I forget? I had accidentally included one of the artworks in the final edit. An entirely black canvas – a black square. Surely, no one could lay claim to that? The artist had spotted his work and accused the brewery of profiting from his art. He settled at roughly half the price of what the whole commercial had cost to make. It was an expensive mistake -– and one we are still paying for. We are still paying for everything.

‘We’ll have to go with fifty-five …’ says Charley, brushing imaginary lint from her jeans.

‘The guy without the tats?’

‘Yes. It’ll cost us less to hire a make-up artist to do some sort of sealife-esque scene on his arm than it will to buy the other guy and his tattoo artist out anyway. They’re similar. Besides, he had a good smile, don’t you think?’ Assuming the sale. She is so beautiful, so clever, so in charge. She rolls her eyes at me behind the monitor. Her bracelets jangle as I put the idea to The German Client in my most obsequious tone. In his office, The German Client nods, sips from a bottle of mineral water, and says, ‘Yes, yes. Okay. We see you Monday.’

~~~

- Extracted from A Short Life by Nicky Greenwall, out now from Penguin Random House SA!

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags A Short Life Book excerpts Book extracts Nicky Greenwall Penguin Random House SA