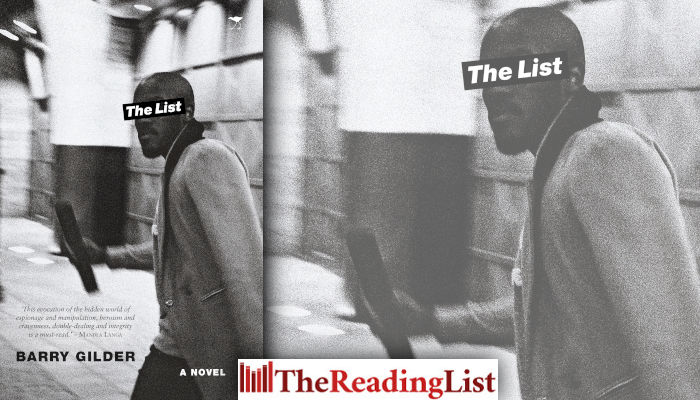

‘I tell this story now because I was there.’ – Read an excerpt from Barry Gilder’s debut novel The List

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Barry Gilder’s debut novel The List!

April 2020

I tell this story now in the knowledge – sound, I’m sure – that the telling is too late. Too late to go back. Too late to tell it again, differently … I tell this story now because I was there. Because I am safe now – relatively, anyway – and once more in drizzling London, an obscure survivor.

Although conceived and birthed well before the ANC’s December 2017 elective conference and the changes of the guard that ensued, The List imagines a ‘New Dawn’ for South Africa in the closing years of the 2010s. But is it dawn or dusk?

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from The List:

~~~

Note No. 1

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

– TS Eliot, ‘The Waste Land’

April 2020

I tell this story now in the knowledge – sound, I’m sure – that the telling is too late. Too late to go back. Too late to tell it again, differently.

I, and those with whom I shared pathways through anger and hope, over our clutched glasses of wine, would certainly have wished to start the story over again. For we knew how it began; we knew how it unfolded; and we thought we knew how it would end.

But history has overtaken us, flashed past us while our gaze was elsewhere, just when we thought we had left it far behind. It has returned. And now there is no retelling of the story. No rewrites. Sekwenzekile!

I tell this story now because I was there. Because I am safe now – relatively, anyway – and once more in drizzling London, an obscure survivor. I scratch this tale with red pen into this red notebook on this antique desk below the cracked window with dirty lime curtains in my Kilburn bedsit. I transmit this tale to the future, for no one who frequents The Old Bell down the road, around the corner from the stone church, would listen to a bent-shouldered, ashen-haired man with gnarled fingers curled too tightly around his pint of bitter, who speaks in fuzzy tones of intrigue and conspiracy.

They would not listen, for the country of which I would speak is far away. Far away in space, and any interest in it now far away in time. Few, anyway, of my pub’s clientele would be old enough to remember when Trafalgar Square was filled with crowds calling freedom for Nelson Mandela. None would remember when Wembley Stadium echoed with music and song and fiery speeches in celebration of the legend’s seventieth birthday. And for those not now too young, the memory of his final freedom and the democratic honeymoon that followed would have faded. And most of the inhabitants of Kilburn now are not London-born – other dark-skinned émigrés with their own tales to tell of other faraway places.

Yes, I was there when The Signs showed themselves. Not that they did so in ways that said, We are Signs, of course, but there was a logic to the road. And the signs were there, not pointing anywhere, just asking to be seen. I was one of the few who pointed them out as we hurtled past, but most said we were imagining them, that we were seeing signs where there were just naked poles.

And, yes, I was there on that unusually icy and wet February 2020 day in the gallery of the Houses of Parliament off Plein Street in Cape Town, when the mist rose up off the crags and slid down from the heavens, obscuring the flat-topped mountain. We were gathered to hear President Moloi deliver his state of the nation address in opening this second session of parliament a year after his rise, some said miraculously, to office. The colours, the daring clothing, the old-world pomp and the new-world singing and ululations. All of us gathered to celebrate the first anniversary of what some called a new beginning. Awoken from the fitful, confused slumber of early democracy, of compromise and prevarication and slow capitulation and decay.

And so I was there when, not many minutes into the president’s speech, a man rose from the benches in the centre of the house and stabbed the president eleven times with a blade concealed in a mobile phone.

It could be said that history regurgitated twice on this day. First in this stabbing in cynical aping of the assassination of the architect of apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd, back in 1966, and secondly in ironic deference to the demise of Lee Harvey Oswald, when in the confusion the perpetrator – in making his escape through the front of the house onto the piazza overlooking Plein Street – was shot by a sniper from a building across the street.

And, yes, I was there, hardly a year before this presidenticide, when Comrade Vladimir recruited me into his very special, very secret task team to investigate The Signs. I thought at the time that this at last was the beginning of the proper ending of the story – a proper rewrite, ruthless red pen bouncing across the pages of history, deleting the impossible, circling the improbable, reinserting the expurgated.

Chapter 1

October 1979

The road, narrow, winding through groves and koppies, seemed endless. The tyres of Otto Bester’s stone-pocked Cressida hummed on the dry rough tar, an insistent whirring of purposefulness. This was his life – itinerant. Each journey across the backroads of the Eastern Transvaal culminating in another assignation, another testing of his ability to reach across the human, the cultural, the racial, the age divides of the intricate mix that was South Africa at the end of the 1970s.

‘At the very next town,’ he told himself, ‘I will stop. I don’t have to, but I need a Coke and some greasy chips.’ And the thought saw him through the next seventy kilometres. As the red sign loomed up ahead, instructing him to decelerate to 80kph, he wound down his window an open hand’s width and lit a cigarette, careful to exhale through the gap. As he passed the first of the 60kph speed signs, he lifted his foot off the accelerator and touched the brakes to get the reluctant car to obey the law.

He found the café, parked, and extricated the thick brown file from the space between seat and console. Inside the café, he found an isolated table and sat with his back to the wall mounted with a large black-and-white image of God’s Window, his face to the door.

From the point of view of the lone waitress, this was a man you served immediately and deferentially, not from around here, probably from the big city, sullen, engrossed in the file on the table before him. She harangued the chef in the kitchen to make haste and delivered the Coke, bending her knees slightly as she placed it in arm’s reach.

Bester put his hand out for the Coke without looking up. This was going to be an interesting one. Lots of promise. Long-term prospects if he played it right. Right age. Right credentials. Malleable attitudes. Good networks. He could go far.

Like an actor for whom stage fright had long dissipated into no more than a tightening of the stomach muscles and a tingling of the palms, Bester felt the stab of anticipation begin to well, a necessary spur to his forthcoming appearance on his own, un-public stage. He rehearsed scenarios in his head, and, as a warm-up, engaged the waitress as she returned with his chips.

‘Lots of grease, hey?’

‘Yes, oom.’

‘You worked here long?’

‘Since I left school, oom. Last year.’

‘You finish school?’

‘Standard eight, oom.’

‘What do they call you at home?’

‘Annetjie, oom.’

‘You must finish school, Annetjie. Then maybe you can get a better job.’

Bester looked into her eyes and smiled the smile. He lifted a chip to his mouth.

‘Yes, oom.’

She bent her knees again and backed away, wiping her palms down the front of her apron, the bottom edge of which hung below the hem of her miniskirt, pushed back the strand of blonde hair that had fallen over her eyes, then turned and walked away.

Pretty, thought Bester. He put another chip in his mouth and turned back to his file. He was almost ready. The contents were committed to memory. He was warmed up. There was just enough time to finish his chips and Coke, smoke a cigarette, and traverse the last stretch of road to make it on time to the desolate spot he had chosen.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Barry Gilder Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media The List

1 Votes

Related

- Don’t miss the launch of Deep Blue: Why We Love the Sea by Veruska De Vita at Salon Hecate (12 Mar)

- Listen to the new episode of Pagecast! Acclaimed local author Nivashni Nair Sukdhev chats about her new novel, It’s Complicated

- Find out more about Michiel Heyns’s remarkable new novel The Wildest Beauty

- Find out more about It’s Complicated – the new romance novel by Nivashni Nair Sukdhev

- Join Shameez Patel for the launch of her new romcom Next Level Love in Cape Town (27 Jan)