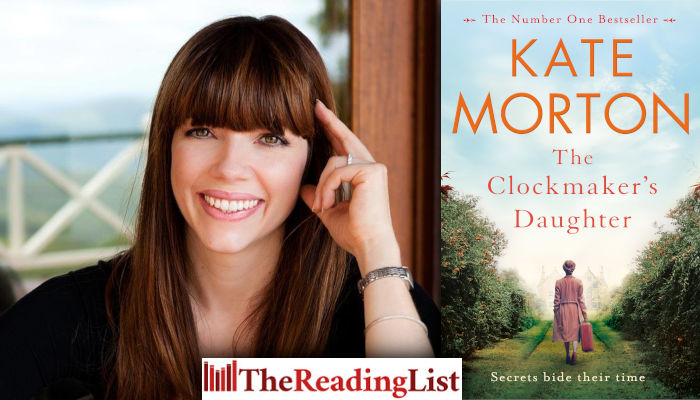

Friday Night Book Club: Read an excerpt from The Clockmaker’s Daughter by Kate Morton – the perfect book to curl up with this evening

More about the book!

The Friday Night Book Club: Exclusive excerpts from Pan Macmillan every weekend!

Staying in this evening? Settle in with some hot chocolate and this excerpt from The Clockmaker’s Daughter by Kate Morton, a novel in which a long-buried secret is waiting to be uncovered …

The Clockmaker’s Daughter is out in paperback at the end of April.

About the book

My real name, no one remembers.

The truth about that summer, no one else knows.

In the summer of 1862, a group of young artists led by the passionate and talented Edward Radcliffe descends upon Birchwood Manor on the banks of the Upper Thames. Their plan: to spend a secluded summer month in a haze of inspiration and creativity. But by the time their stay is over, one woman has been shot dead while another has disappeared; a priceless heirloom is missing; and Edward Radcliffe’s life is in ruins.

Over one hundred and fifty years later, Elodie Winslow, a young archivist in London, uncovers a leather satchel containing two seemingly unrelated items: a sepia photograph of an arresting-looking woman in Victorian clothing, and an artist’s sketchbook containing the drawing of a twin-gabled house on the bend of a river.

Why does Birchwood Manor feel so familiar to Elodie? And who is the beautiful woman in the photograph? Will she ever give up her secrets?

Told by multiple voices across time, The Clockmaker’s Daughter is a story of murder, mystery and thievery, of art, love and loss. And flowing through its pages like a river, is the voice of a woman who stands outside time, whose name has been forgotten by history, but who has watched it all unfold: Birdie Bell, the clockmaker’s daughter.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Chapter One

Summer 2017

It was Elodie Winslow’s favorite time of day. Summer in London, and at a certain point in the very late afternoon the sun seemed to hesitate in its passage across the sky and light spilled through the small glass tiles in the pavement directly onto her desk. Best of all, with Margot and Mr. Pendleton gone home for the day, the moment was Elodie’s alone.

The basement of Stratton, Cadwell & Co., in its building on the Strand, was not an especially romantic place, not like the muniment room at New College where Elodie had taken holiday work the year she completed her master’s. It was not warm, ever, and even during a heat wave like this one Elodie needed to wear a cardigan at her desk. But every so often, when the stars aligned, the office, with its smell of dust and age and the seeping Thames, was almost charming.

In the narrow kitchenette behind the wall of filing cabinets, Elodie poured steaming water into the mug and flipped the timer. Margot thought this precision extreme, but Elodie preferred her tea when it had steeped for three and a half minutes exactly.

As she waited, grains of sand slipping through the glass, Elodie’s thoughts returned to Pippa’s message. She had picked it up on her phone, when she’d ducked across the road to buy a sandwich for lunch: an invitation to a fashion launch party that sounded as tempting to Elodie as a stint in the doctor’s waiting room. Thankfully, she already had plans – a visit to her father in Hampstead to collect the recordings he’d put aside for her – and was spared the task of inventing a reason to say no.

Denying Pippa was not easy. She was Elodie’s best friend and had been since the first day of grade three at Pineoaks Primary School. Elodie often gave silent thanks to Miss Perry for seating the two of them together: Elodie, the New Girl, in her unfamiliar uniform and the lopsided plaits her dad had wrestled into place; and Pippa, with her broad smile, dimpled cheeks, and hands that were in constant motion when she spoke.

They’d been inseparable ever since. Primary school, high school, and even afterwards when Elodie went up to Oxford and Pippa to Central Saint Martins. They saw less of one another now, but that was to be expected: the art world was a busy, sociable place, and Pippa was responsible for a never-ending stream of invitations left on Elodie’s phone as she made her way from this gallery opening or installation to the next.

The world of archives, by contrast, was decidedly unbusy. That is, it was not busy in Pippa’s sparkling sense. Elodie put in long hours and engaged frequently with other human beings; they just weren’t the living, breathing sort. The original Messrs. Stratton and Cadwell had traversed the globe at a time when it was just beginning to shrink and the invention of the telephone hadn’t yet reduced reliance on written correspondence. So it was, Elodie spent her days communing with the foxed and dusty artifacts of the long-dead, stepping into this account of a soirée on the Orient Express or that encounter between Victorian adventurers in search of the Northwest Passage.

Such social engagement across time made Elodie very happy. It was true that she didn’t have many friends, not of the flesh-and-blood variety, but the fact did not upset her. It was tiring, all that smiling and sharing and speculating about the weather, and she always left a gathering, no matter how intimate, feeling depleted, as if she’d accidentally left behind some vital layers of herself she’d never get back.

Elodie removed the tea bag, squeezed the last drips into the sink, and added a half-second pour of milk.

She carried the mug back to her desk, where the prisms of afternoon sunlight were just beginning their daily creep; and as steam curled voluptuously and her palms warmed, Elodie surveyed the day’s remaining tasks. She had been midway through compiling an index on the younger James Stratton’s account of his 1893 journey to the west coast of Africa; there was an article to write for the next edition of Stratton, Cadwell & Co. Monthly; and Mr. Pendleton had left her with the catalogue for the upcoming exhibition to proofread before it went to the printer.

But Elodie had been making decisions about words and their order all day, and her brain was stretched. Her gaze fell to the waxedcardboard box on the floor beneath her desk. It had been there since Monday afternoon when a plumbing disaster in the offices above had required immediate evacuation of the old cloakroom, a low-ceilinged architectural afterthought that Elodie couldn’t remember entering in the ten years since she’d started work in the building. The box had turned up beneath a stack of dusty brocade curtains in the bottom of an antique chiffonier, a handwritten label on its lid reading, ‘Contents of attic desk drawer, 1966 – unlisted.’

Finding archival materials in the disused cloakroom, let alone so many decades after they’d apparently been delivered, was disquieting, and Mr. Pendleton’s reaction had been predictably explosive. He was a stickler for protocol, and it was lucky, Elodie and Margot later agreed, that whoever had been responsible for receiving the delivery in 1966 had long ago left his employ.

The timing couldn’t have been worse: ever since the management consultant had been sent in to ‘trim the fat,’ Mr. Pendleton had been in a spin. The invasion of his physical sphere was bad enough, but the insult of having his efficiency questioned was beyond the pale. ‘It’s like someone borrowing your watch to tell you the time,’ he’d said through frosted lips after the consultant had met with them the other morning.

The unceremonious appearance of the box had threatened to tip him into apoplexy, so Elodie – who liked disharmony as little as she did disorder – had stepped in with a firm promise to set things right, promptly sweeping it up and stashing it out of sight.

In the days since, she’d been careful to keep it concealed so as not to trigger another eruption, but now, alone in the quiet office, she knelt on the carpet and slid the box from its hiding place …

The pinpricks of sudden light were a shock, and the satchel, pressed deep inside the box, exhaled. The journey had been long and it was understandably weary. Its edges were wearing thin, its buckles had tarnished, and an unfortunate musty odor had staled in its depths. As for the dust, a permanent patina had formed opaquely on the once-fine surface, and it was now the sort of bag that people held at a distance, turning their heads to one side as they weighed the possibilities. Too old to be of use, but bearing an indefinable air of historic quality precluding its disposal.

The satchel had been loved once, admired for its elegance – more importantly, its function. It had been indispensable to a particular person at a particular time when such attributes were highly prized. Since then, it had been hidden and ignored, recovered and disparaged, lost, found, and forgotten.

Now, though, one by one, the items that for decades had sat atop the satchel were finally being lifted, and the satchel, too, was resurfacing at last in this room of faint electrical humming and ticking pipes.

Of diffuse yellow light and papery smells and soft white gloves.

At the other end of the gloves was a woman: young, with fawnlike arms leading to a delicate neck supporting a face framed by short black hair. She held the satchel at a distance, but not with distaste.

Her touch was gentle. Her mouth had gathered in a small, neat purse of interest, and her dark eyes narrowed slightly before widening as she took in the hand-sewn joins, the fine Indian cotton, and the precise stitching.

She ran a soft thumb over the initials on the front flap, faded and sad, and the satchel felt a frisson of pleasure. Somehow this young woman’s attention hinted that what had turned out to be an unexpectedly long journey might just be nearing its end.

Open me,the satchel urged. Look inside.

Once upon a time the satchel had been shiny and new. Made to order by Mr. Simms himself at the royal warrant manufactory of W. Simms & Son on Bond Street. The gilt initials had been hand-tooled and heatsealed with enormous pomp; each silver rivet and buckle had been selected, inspected, and polished; the fine-quality leather had been cut and stitched with care, oiled, and buffed with pride. Spices from the Far East – clove and sandalwood and saffron – had drifted through the building’s veins from the perfumery next door, infusing the satchel with a hint of faraway places. Open me …

The woman in the white gloves unlatched the dull silver buckle and the satchel held its breath.

Open me, open me, open me …

She pushed back its leather strap and for the first time in over a century light swept into the satchel’s dark corners.

An onslaught of memories – fragmented, confused – arrived with it: a bell tinkling above the door at W. Simms & Son; the swish of a young woman’s skirts; the thud of horses’ hooves; the smell of fresh paint and turpentine; heat, lust, whispering. Gaslight in railway stations; a long, winding river; the wheat fragrance of summer –

The gloved hands withdrew and with them went the satchel’s load.

The old sensations, voices, imprints, fell away, and everything, at last, was blank and quiet.

It was over.

Elodie rested the contents on her lap and set the satchel to one side. It was a beautiful piece which did not fit with the other items she’d taken from the box. They had comprised a collection of rather humdrum office supplies – a hole punch, an inkwell, a wooden desk insert for sorting pens and paper clips – and a crocodile leather spectacle case, which the manufacturer’s label announced: ‘The property of L.S-W.’ This fact suggested to Elodie that the desk, and everything inside, had once belonged to Lesley Stratton-Wood, a great-niece down one of the family scions

of the original James Stratton. The vintage was right – Lesley Stratton-Wood had died in the 1960s – and it would explain the box’s delivery to Stratton, Cadwell & Co.

The satchel, though – unless it was a replica of the highest order – was far too old to have belonged to Ms. Stratton-Wood; the items inside looked pre–twentieth century. A preliminary riffle revealed a monogrammed black journal (E.J.R.) with a marbled foreedge; a brass pen box, mid-Victorian; and a faded green leather document holder. There was no way of knowing at first glance to whom the satchel had belonged, but beneath the front flap of the document case, the gilt-stamped label read, ‘James W. Stratton, Esq. London, 1861.’

The leather document holder was flattish, and Elodie thought at first that it might be empty; but when she opened the clasp, a single object waited inside. It was a delicate silver frame, small enough to fit within her hand, containing a photograph of a woman. She was young, with long hair, light but not blond, half of which was wound into a loose knot on the top of her head; her gaze was direct, her chin slightly lifted, her cheekbones high. Her lips were set in an attitude of intelligent engagement, perhaps even defiance.

Elodie felt a familiar stirring of anticipation as she took in the sepia tones, the promise of a life awaiting rediscovery. The woman’s dress was looser than might be expected for the period. White fabric draped over her shoulders, and the neckline fell in a V. The sleeves were sheer and billowed, and had been pushed to the elbow on one arm. Her wrist was slender, the hand on her hip accentuating the indentation of her waist.

The treatment was as unusual as the subject, for the woman wasn’t posed inside on a settee or against a scenic curtain, as one might expect in a Victorian portrait. She was outside, surrounded by dense greenery, a setting that spoke of movement and life. The light was diffuse, the effect intoxicating.

Elodie set the photograph aside and took up the monogrammed journal. It fell open to reveal thick cream pages of expensive cotton paper; there were lines of beautiful handwriting, but they were complements only to the many pen and ink renderings of figures, landscapes, and other objects of interest. Not a journal, then: this was a sketchbook.

A fragment of paper, torn from elsewhere, slipped from between two pages. A single line raced across it: I love her, I love her, I love her, and if I cannot have her I shall surely go mad, for when I am not with her I fear –

The words leapt off the paper as if they’d been spoken aloud, but when Elodie turned over the page, whatever the writer had feared was not revealed.

She ran her gloved fingertips over the impressions of the text. When held up to the last glimmer of sunlight, the paper revealed its individual threads, along with tiny lucent pinpricks where the sharp nib of the fountain pen had torn across the sheet.

Elodie laid the jagged piece of paper gently back inside the sketchbook.

Although antique now, the urgency of its message was unsettling: it spoke forcefully and currently of unfinished business.

Elodie continued to leaf carefully through the pages, each one filled with cross-hatched artist’s studies with occasional roughsketched facial profiles in the margins.

And then she stopped.

This sketch was more elaborate than the others, more complete. A river scene, with a tree in the foreground and a distant wood visible across a broad field. Behind a copse on the right-hand side, the twingabled roofline of a house could be seen, with eight chimneys and an ornate weather vane featuring the sun and moon and other celestial emblems.

It was an accomplished drawing, but that’s not why Elodie stared. She felt a pang of déjà vu so strong it exerted a physical pressure around her chest.

She knew this place. The memory was as vivid as if she’d been there, and yet somehow Elodie knew that it was a location she’d visited only in her mind.

The words came to her then as clear as birdsong at dawn: ‘Down the winding lane and across the meadow broad, to the river they went with their secrets and their sword.’

And she remembered. It was a story that her mother used to tell her. A child’s bedtime story, romantic and tangled, replete with heroes, villains, and a Fairy Queen, set in a house within dark woods encircled by a long, snaking river.

But there had been no book with illustrations. The tale had been spoken aloud, the two of them side by side in her little girl bed in the room with the sloping ceiling –

The wall clock chimed, low and premonitory, from Mr. Pendleton’s office, and Elodie glanced at her watch. She was late. Time had lost its shape again, its arrow dissolving into dust around her. With a final glance at the strangely familiar scene, she returned the sketchbook with the other contents to its box, closed the lid, and pushed it back beneath the desk.

Elodie had gathered her things and was halfway through the usual motions of checking and locking the department door to leave, when the overwhelming urge came upon her. Unable to resist, she hurried back to the box, dug out the sketchbook, and slipped it inside her bag.

~~~

Categories Fiction International

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Friday Night Book Club Kate Morton Pan Macmillan SA The Clockmaker’s Daughter