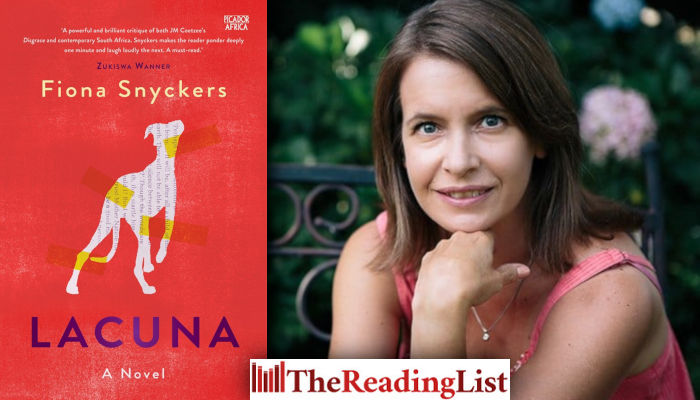

Friday Night Book Club: Read an excerpt from Lacuna, the highly anticipated new novel from Fiona Snyckers

More about the book!

The Friday Night Book Club: Exclusive excerpts from Pan Macmillan every weekend!

Staying in this evening? Settle in with a glass of wine and this excerpt from Fiona Snyckers’s new novel, Lacuna, a response to JM Coetzee’s Disgrace, written from the point of view of Lucy Lurie.

About the book

‘A powerful and brilliant critique of both JM Coetzee’s Disgrace and contemporary South Africa. Fiona Snyckers makes the reader ponder deeply one minute and laugh loudly the next. A must read.’

– Zukiswa Wanner‘It is substantive, thoughtful, and also, in terms of writing technique, exceptionally well crafted … Snyckers will win many awards for this one.’

– Eusebius McKaiser

In this brilliant response to JM Coetzee’s Disgrace, author Fiona Snyckers really puts herself and her immense writing talent right out there.

Lucy Lurie is deeply sunk in PTSD following a gang rape at her father’s farmhouse in the Western Cape.

She becomes obsessed with the author John Coetzee, who has made a name for himself by writing Disgrace, a celebrated novel that revolves around the attack on her. Lucy lives the life of a celibate hermit, making periodic forays into the outside world in her attempts to find and comfort Coetzee.

The Lucy of Coetzee’s fictional imaginings is a passive, peaceful creature, almost entirely lacking in agency. She is the lacuna in Coetzee’s novel – the missing piece of the puzzle.

The Lucy Lurie of Fiona Snyckers’ imagination is no one’s lacuna. Her attempts to claw back her life, her voice and her agency may be messy and misguided, but she won’t be silenced. Her rape is not a metaphor. This is her story.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Chapter 1

A lacuna is an unfilled space or gap. My vagina is a lacuna that my attackers filled with their penises. They saw the lack in me and chose to supply what I couldn’t. Their penises were rough and dry and scraped my lacuna raw, bruising my cervix, and tearing my perineum. Sometimes I dream that my rape is happening off-stage – in the manner of the ancient Greek tragedians. I am lying in another room and listening to it. I can hear my cries of pain – loud at first, then softening to whimpers. I can hear their grunts of frustration and triumph. One of them manages to ejaculate, which he does with a roar of victory. I can’t feel what is happening or even see it, except in my imagination. The soundtrack on the other side of the wall lets me know how far they have progressed.

Now they are taking a break. Now they have got their second wind and are starting again. It is less harrowing than being in that room myself. Experiencing something at one remove is a pale shadow of the real thing. The ancient Greek tragedians were wrong if they thought that leaving the rough stuff to the readers’ imaginations was more effective than rubbing our noses in it. But perhaps that wasn’t their intention at all. Perhaps they simply thought it was more genteel to keep ugliness off the stage. No one wants to watch stomach-turning violence at the theatre, especially over dinner. It can be very upsetting.

Was that what Coetzee was doing? Was he being genteel – tiptoeing around the sensibilities of his readers? Or did he believe it would be more effective for the rape to take place off-stage in the arena of the reader’s imagination? Coetzee apologists have suggested that he was making a feminist point by leaving that lacuna unfilled in the text – that he was illustrating how rape victims are stripped of agency and denied a voice. I see it as a lacuna in his own literary imagination. He does not supply details on the page because his imagination failed him when it came to describing what happened to me. You don’t want to hear this, do you? There is nothing more tedious than a rageful harpy ranting about some cherished grievance. It’s so 1981. So Andrea Dworkin. So Catharine MacKinnon.

Let me tell you what John Coetzee was like as a colleague instead. I say colleague, but remember, he was the Rawlings Professor of Apolitical Close Reading while I was a junior lecturer on a one-year, non-renewable contract. In corporate terms, this would be the equivalent of the CEO of a multinational corporation being regarded as a colleague of the mould growing on the underside of the cleaner’s bucket. It is impossible to overstate what a gap in status there was between us.

Furthermore, he was a man and I was a very young woman. You might think this is irrelevant, but that would prove how little you know about the generation of academics Coetzee represents. Coetzee and I interacted face-to-face on three occasions. I should describe them for you. Show, not tell. That’s Memoir Writing 101. Not easy for those of us trained in academic exegesis. We have been schooled to tell, with very little need to show.

The first occasion was at my thesis defence seminar, before I got the junior lectureship. This is part of how PhDs are awarded at the University of Constantia: your thesis is read by a panel of your peers, before whom you appear in person to defend your work against such questions and comments as they might want to put to you. This is known as your thesis defence. Mine went by in a blur, but some moments stand out. One is of Prof Coetzee asking me whether I agreed that feminist literary theory had ‘run its course’. This was in the middle of my animated discussion with a professor from the African Studies Department about whether the particular strand of Afrofuturistic feminist methodology I had chosen was the correct paradigm to apply to the texts in question. He also asked whether I was married or intended to have children, without explaining why these points were relevant.

Later I heard that my thesis had been passed – provided I expanded two sections and corrected a few typos – by a majority of five panellists to one. I had no doubt who that one hold-out panellist was. At the time, it didn’t trouble me. John Coetzee’s questions about feminist methodology and my marital status became comic fodder for me to recycle among my friends at the Cap & Gown pub near campus. Prof Coetzee was an anachronism. His time was up. He and the generation he represented were history. Coetzee’s failed literary ambitions were an open secret at the university. The unfinished manuscript was a running joke among undergraduates at the University of Constantia, who used to quote bits of its cringeworthy dialogue to each other. Never did we imagine that he was a whisker away from writing the book that would scoop that year’s major literary awards. He was about to become South Africa’s next Booker Prize winner. First Nadine Gordimer, and now John Coetzee. We would have choked on our beers laughing if anyone had suggested such a thing.

The second time Coetzee and I came face-to-face was at my interview for the one-year rotating post of junior lecturer. As is common in job interviews, there came a time when the panel asked me if I had any questions to put to them. I asked if there was a chance of the post being extended into something more long-term. Coetzee responded by asking whether I was happy with the maternity-leave provisions in the contract or whether I would wish to see them extended. The message was clear. He wasn’t about to award a permanent post to a young woman who would be popping out babies at the first opportunity.

The third time was in the general office of the English Department. The main attraction of this office was its laser printer. Those members of staff who were too poor (like me) or too cheap (like Prof Coetzee) to buy their own printers were allowed to send documents to the office printer. You had to be light on your feet when it came to collecting your document, or you might find it thrown into the recycling bin or scattered around the office. On this day, I had sent a reading list to the printer. As soon as I pressed send, I jogged along the corridor to the office to pick it up. I found John Coetzee staring at the printer with an air of puzzlement as it spat out twenty-five copies of my second-year reading list. I readied my politest smile as I walked up to the printer. This was the most senior member of the department, after all. He made no eye contact. Only when my print run was finished, and I reached into the tray to collect my reading list, did he speak.

‘This printer is for the use of staff members only.’

‘That’s right,’ I agreed.

‘Staff members of the English Department.’

‘I know.’ There was a pause as he stared at me.

‘I’m a junior lecturer.’ My voice came out higher and younger than I wanted it to. ‘In this department.’ You interviewed me, I wanted to add, before self-respect stopped me.

The accusing stare didn’t lift. The printer lurched into life again.

‘Look!’ I said. ‘Here comes your document now.’

Up to that moment, I had been under the impression that I was making a mark on the department with my diligence and enthusiasm. The bigwigs were noticing. If I made myself indispensable, my contract might be renewed at the end of the year. The realisation that a senior professor was unaware of my existence put paid to that delusion. Imagine my surprise to find myself, a year later, one of the central characters in Coetzee’s novel. He even used my full name, Lucy Lurie. It was as though he were daring me to sue him, knowing I didn’t have the means or the resolution to do so.

Lucy means ‘light’ in Greek. Scholars have made much of his use of nominative determinism in the book. Lucy is the moral centre of the novel – an unwavering source of light and goodness. She is an unflawed character, apart from some amusing mannerisms. She has a way of walking with her toes turned out like a duck – a legacy of her early training as a dancer. She blinks her eyes and screws up her nose when she gets tired or when her contact lenses irritate her. When she is talking to someone who makes her uneasy, she twists a strand of hair around her forefinger until it hangs lankly by the side of her face. When she believes herself to be unobserved, she sucks on her baby finger until it becomes wrinkled and bloodless. These are my mannerisms. Only one who has observed me closely would notice them.

I want to shrink when I think of Coetzee observing my hank of over-fingered hair. Mortification slaps me on both cheeks when I realise he must have walked past my office and seen me sucking my finger. The man who pretended not to recognise me when I ran into him in the general office had been watching me all that time, cataloguing my habits. The critics ate it up. It was so perfectly Coetzee-ish (yes, that is now a word) to humanise an otherwise angelic character by giving her a laundry list of bathetic qualities.

~~~

I don’t see many people from the English Department these days, but my friend Moira comes around sometimes. She asks whether I’m flattered to realise how carefully Coetzee had been watching me. I tell her I’m not. Not at all. But that’s a lie. Something within me blooms under the warm, acknowledging gaze of a clever older man. I feel worthy. Validated. I feel like I exist. Like I matter. And I despise myself for feeling like that.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Disgrace Fiona Snyckers Friday Night Book Club JM Coetzee Lacuna Pan Macmillan SA