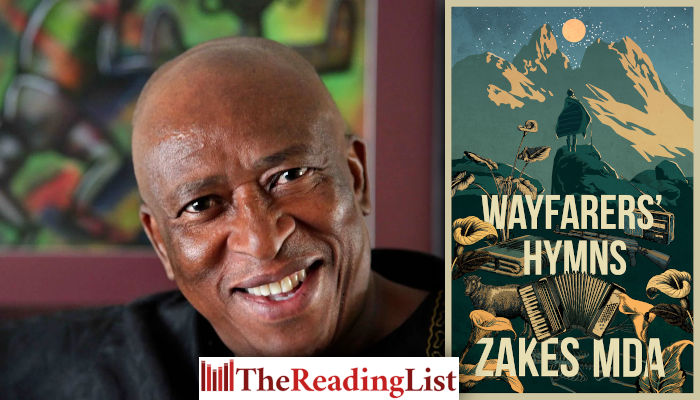

‘Famo was the music I grew up listening to’ – Zakes Mda chats about his new novel Wayfarers’ Hymns

More about the book!

Zakes Mda’s new book, Wayfarers’ Hymns, is set in the fascinating world of famo music. He chatted to Lauren Mc Diarmid about the novel, his years living in Lesotho and stories that demand to be told.

The story in Wayfarers’ Hymns came after I had decided to retire from writing novels. I was determined that The Zulus of New York was going to be my last novel, and I had announced that to the world. The story assailed me, grabbed me by the scruff of my neck and demanded that I narrate it. I had no say. The story decides when it should be told, and how it should be told. If it tells me that it can only be a song, or in some other instance a poem, or a play, or a painting, I never force it to be a novel. I tell it exactly as it demands to be told. So finally, I had to obey.

Wayfarers’ Hymn travels from Lesotho’s Mountain Kingdom to the City of Gold through the history of famo. It follows our boy-child, a wandering musician and a weaver of songs. His own story is intertwined with the social history of the music: the Time of the Concertina and the Accordion, the wars of the famo gangs, and the battle for control of illegal mines.

Famo music was born in the drinking dens of migrant mineworkers in Lesotho, where the men would sing to unwind after work, accompanied by the accordion, a drum and sometimes a bass. This was the music I grew up listening to. From my years living in Lesotho, I remember a concertina man called Pshoatla, who was famous throughout Lesotho. Those were the days of the concertina. And then came the organ, which was immediately followed by the accordion.

I did not know most of these famo musicians personally until I researched this novel, but as a professor at the University of Lesotho, I used to invite some of these musicians to perform for my theatre class, as our mode of theatre-for-development used popular forms of artistic expression, including music. One of those musicians was a woman called Mmalitaba, a fierce famo singer and dancer. The Puseletso Seema that I write about in Wayfarers’ Hymns, who is still very active to this day, wouldn’t have been the performer she became if Mmalitaba had not lived.

So the book brings in some of my own memories and experiences. Village life, for instance. Though I lived in the town in Lesotho, my father being a lawyer, I interacted with the rural culture a lot. The music of course spilled into the urban areas. It is also my third novel featuring professional mourner, Toloki.

The decision to bring Toloki into this story was made many years ago; in 2006, after I completed Cion, which also features Toloki, but without his partner, Noria because it is mentioned there in passing that she died in Lesotho. I knew then that the next time I wrote a novel set in Lesotho, whatever the story would be, it would have to account for the death of Noria. It had to be a Toloki Trilogy. Of course, at the time I didn’t know that the novel would be about these musicians and gangsters.

I hadn’t known of the involvement of the musicians in illegal mining and police corruption in South Africa, in gang warfare, in Lesotho politics, and so forth, until I spoke with the musicians themselves. The main person who led me to the musicians, and therefore on this journey, was Sebonomoea Ramainoane, a radio station owner, pastor, farmer, newspaper editor and musician in his own right, whom I have known from the early days of his youth. The journey led me to the history of MaRussia, the gangs of Basotho men that were active in those townships of Soweto that were predominantly Sesotho. I wrote about MaRussia in my second novel, She Plays with the Darkness, some years back. These musicians and their gangs are descendants of the MaRussia gangs, named after the Russians who were held in awe by Basotho warriors as fierce soldiers.

I could never say what I hope readers will gain from reading Wayfarers’ Hymns. Anyone who reads the book will take from it what they will. My role is to tell the story; the reader’s is to fill in the gaps through the lens of their own life’s experiences. That is why a reader can tell me that “this book changed my life”, even though I had no intentions of changing anyone’s life. The story must speak for itself.

Wayfarers’ Hymns is out now.

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

Categories Fiction Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Penguin Random House SA The Penguin Post Wayfarers' Hymns Zakes Mda