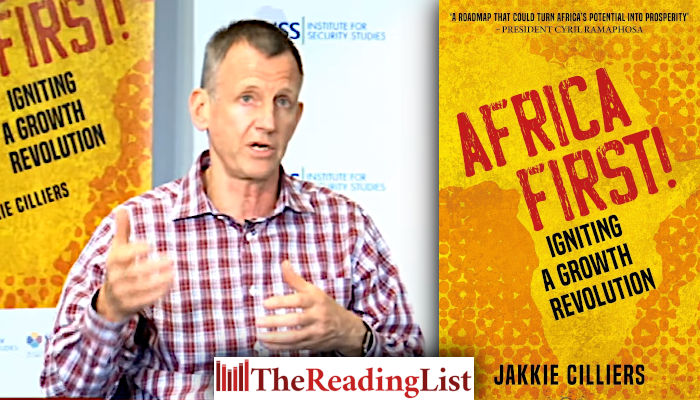

China’s growing footprint in Africa – Read an excerpt from Africa First! Igniting a Growth Revolution by Jakkie Cilliers

More about the book!

Jonathan Ball Publishers has shared an excerpt from Africa First! Igniting a Growth Revolution by Jakkie Cilliers.

What stops Africa, with its abundant natural resources, from capitalising on its boundless potential? In Africa First! well-known Africa analyst Cilliers uses 11 scenarios to unpack, in concrete terms, how the continent can ignite a growth revolution that will take millions out of poverty and into employment.

The Reading List is hosting a virtual book launch for Africa First! on Facebook Live on Tuesday 21 April 2020 at 6pm CAT! Cilliers will be in conversation with Nastassia Arendse.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

China’s growing footprint in Africa

Africa is the third-largest destination for Chinese investment, after Asia and Europe. Foreign direct investment (FDI) growth rates from China to Africa were up 25 per cent from 2010 to 2014, followed by 13 per cent from South Africa and only 10 per cent from the US.

In a comprehensive study on China in Africa, the McKinsey Global Institute concludes that ‘the Africa-China opportunity is larger than that presented by any other foreign partner – including Brazil, the European Union, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States’. The authors set out two scenarios.

In the first, revenues of Chinese firms in Africa grow from US$180 billion to around US$250 billion in 2025. The second scenario sees Chinese firms in Africa expand aggressively in both existing and new sectors, achieving revenues of US$440 billion in 2025. Together with the proposed increases set out by the UK and steady improvements in stability in North Africa, growth in FDI flows to Africa could realistically return to levels of around 15 to 20 per cent per annum over the next five years.

The International Futures (IF) Current Path forecast (which is discussed in the book) is that inflows from FDI to Africa will increase from the current 3.1 per cent of GDP per annum to around 3.7 per cent by 2040, ie roughly equivalent to the size of the African economy as a portion of the global economy. This will continue a trend that has seen FDI flows overwhelmingly go to Asia.

Africa has already benefited significantly from China’s remarkable economic transition over the last two decades, first through its demand for commodities, second by China’s positive balance of payments (ie it had funds to invest) and finally from the Belt and Road Initiative. The continent was not part of the original scheme, and was only included in 2015 as it and other regions clamoured to benefit from potential investments in infrastructure.

Investments inevitably require collateral, pointing to another advantage for China, which has proven flexible in accepting ‘non-traditional’ collateral. In fact, China’s willingness to accept airports, harbours and future commodity exports (or even mines) as security has raised alarm bells in the US, which sees this as a ploy for China to lay its hands on strategic infrastructure.

This complaint is, however, seldom a concern in Africa, although there have been any number of instances in which African governments have been induced to enter into expensive prestige projects (such as the airport in Lusaka) and apparently overpriced railway lines (such as the Mombasa–Nairobi standard-gauge line). And then there is the Chinese habit of trying to tie countries, for example Angola and South Sudan, into agreements in which it pays for commodities by offering the services of Chinese companies.

But there is also clear evidence that Beijing is concerned about the ability of key African governments to service their loans from China. A more serious concern, often repeated in the mainstream media, is that many of the large Chinese construction (and other) projects apparently provide little work for locals. This was clearly the case in the past, but extensive recent field research in Ethiopia and Angola would indicate that national labour participation is substantially higher than generally assumed in Western media, that wages in Chinese firms abroad are largely similar to other firms in the same sector, and that Chinese firms contribute as much to training and skills development as do other companies in the same sector.

Then there is the issue of quality, which is often quite poor, and the extent to which China is ‘exporting corruption’ in the way it uses development assistance to buy influence (and contracts) from African leaders. Nor are these companies able to be held to account domestically in China through shareholder activism or public disclosure.

The problem with the quality argument, borne out by many travels across Africa, is that Africans generally get what they pay for (low quality at low prices) and that an argument can be made that much is of ‘appropriate’ quality. German precision standards on building a road or culvert are hardly applicable in rural Congo. Eventually, Africans get what they negotiate as part of the initial agreements and what they subsequently hold their partners to account for, including the use of local labour and technology transfers.

This brings us to the most important difference in Chinese versus Western practices, namely, that large Chinese loans do not come with a requirement to discuss matters around the rule of law, good governance or human rights, as is done by the IMF and the World Bank. China simply does not share the views and approaches of the West in terms of the rule of law, corruption and what have generally become known as standards of good governance.

The advantages listed above are not unique to Africa. China has run a year-on-year positive trade balance for decades, with the result that total overseas lending from China’s two largest state banks amounted to US$675 billion at the end of 2016 – already more than twice the size of World Bank loans. A very modest portion of this goes to Africa.

At the time of writing, Chinese lending to Africa is likely to decline amid concerns about high debt levels. In fact, Africa is steadily moving down the Chinese list of priorities as its economy transitions away from infrastructure investment and commodity dependence towards domestic consumption.

The change could have an important impact in Africa, for China has become the biggest single-country funder and builder of infrastructure projects in Africa, having spent about US$11.5 billion per annum since 2012. China is therefore the largest contributor in helping to fill Africa’s gap in infrastructure, which the African Development Bank estimates at anything between US$130 to US$170 billion annually.

In addition to the visible, large, state-led infrastructure companies from China active on the continent, McKinsey estimates that there are more than 10 000 privately owned small Chinese companies operating in Africa. This number is substantially more than official data from China’s Ministry of Commerce. McKinsey concludes that China’s engagement in Africa is ‘unparalleled’ and that the true picture is understated, with total financial flows around 15 per cent higher than official figures convey.

Although there is a dearth of data on the precise nature and scale of China’s investments and overseas lending, including in Africa,37 there is a clear danger that through the combined impact of China and others, a number of African countries could again find themselves in a debt trap similar to that of the 1980s. In January 2019 the IMF assessed that about 17 low-income African countries were in, or at risk of, debt distress. Loans from China played a role in only a few, however.

Debt can be a severe constraint on growth. In a wide-ranging study on the relationship between debt and growth, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff conclude: ‘When external debt reaches 60 per cent of GDP, annual growth declines by about two per cent.’

On average, Africa’s low-income and lower-middle-income countries consistently had debt levels in excess of 60 per cent of GDP from the mid-1980s for almost two subsequent decades, levels that clearly contributed to slow growth. Looking ahead, without preventive measures, rising debt levels could again constrain Africa’s growth.

Infrastructure is not the only (Chinese) game in town. To ease the long-running pressure on the naira after it started steadily losing value against the US dollar in 2015, Nigeria began selling Chinese renminbi (yuan) to local traders and business. The move has made it easier for local businesses in Nigeria to trade and engage with their Chinese counterparts without the need to first convert their local currency to dollars.

After the 2015 drop in global oil prices, Nigeria faced a major dollar shortage and its foreign reserves dwindled. Setting up the renminbi as an alternative trading currency eases all of this, although China’s conditions and requirements for funding and loans have also hardened of late. A number of other African countries have subsequently followed suit.

To safeguard its growing investments, China has expanded its direct and indirect role in peace and security in Africa, as Europe and the US did in previous decades. In addition to a naval base in Djibouti, the inaugural China-Africa Defence and Security Forum, held in June/July 2018, established an overarching framework for China’s security programmes in Africa.

In February 2019 China announced that it had provided US$180 million to fund peace and security efforts in Africa and that it was already the largest supplier of weapons to sub-Saharan Africa. China’s role in support of the AU and numerous African armed forces is steadily expanding, as are its efforts at mediation.

~~~

Categories Africa Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Africa First! Book excerpts Book extracts Jakkie Cilliers Jonathan Ball Publishers