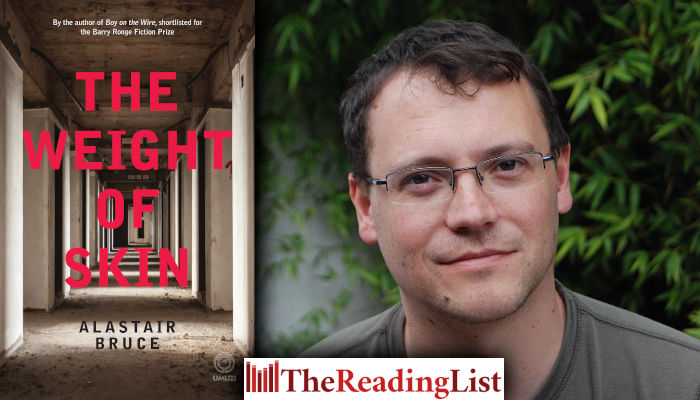

‘The law is clear. Your country no longer exists.’ Read an excerpt from The Weight of Skin, the new novel by Alastair Bruce

More about the book!

Penguin Random House SA has shared an extract from Alastair Bruce’s newly published novel The Weight of Skin.

Bruce is the author of the critically acclaimed novels Wall of Days and Boy on the Wire. He was born in Port Elizabeth, spending a large part of his childhood on a smallholding outside the city. He currently lives in Buckinghamshire, England, with his wife and two young children.

About the book

‘You would not think it to look at you, but your voice, when you use it: akin to a god’s. You must be careful what you do with it.’

Exiled Jacob Kitara takes in injured compatriots and nurses them in a boarded-up building. Social unrest has emptied the streets of London, movement into and out of the country has been suspended, and those who remain are in hiding.

When a young man makes his appearance, insisting that he is Jacob’s son – a man presumed dead, torn from Jacob’s life by war and guilt over the fate of the boy’s mother – Jacob is driven to anger.

But can this stranger offer Jacob a chance to reach back to a different continent, to the foot of Africa from where he has been banished, to atone for the past?

The Weight of Skin is a poignant tale of personal and political responsibility, and of the intricate narratives of family and nationality that bind us.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

He meets his handler on the southbound platform of the Bakerloo line. Ahead of Kitara, when he steps onto the platform, his footsteps echoing, is an advert for a mobile phone. He turns left, and at the far end of the platform, sitting at a desk lit by a single lamp, is his contact, a man called Smith, though he doubts this is his real name.

The man does not look up until Kitara is a few metres away.

‘Kitara.’ He says this not by way of greeting but simply as a statement of fact, and then looks back down at his papers, pen in hand.

There is no chair in front of the desk so Kitara remains standing.

‘Report.’

The words just come out. ‘There is no change.’ He had not thought about his answer till now but knows that he was not going to tell.

‘No change?’ Smith stops writing and looks up. ‘No one in the past two weeks?’

Kitara remembers the policeman. If he reported the incident then they will know.

He answers, ‘There are few of us left. You have done a good job.’ He does not know why he lies, why he takes the chance. For what, a single word on a piece of paper that could have come from anywhere?

Smith looks down again. ‘You had two males last time, and one female. They are still there?’

‘Yes. They will be released next week.’

‘The usual time, of course.’

It is not phrased as a question and Kitara does not respond.

‘And what have they told you?’

‘Nothing. One mentioned a hideout on Boscobel Street but he says it was months ago that he was there and he was the last of them anyway. They are loners. They do not have knowledge of others.’

‘You are sure of this?’

‘I have done everything I can.’

Smith puts his pen on the table, gets up and walks around to Kitara.

‘You have brought us very little recently.’

‘As I say, you appear to have rounded up everyone.’

Smith says nothing but turns and sits down again.

‘What are you doing with them?’

‘You know what we are doing.’

‘Humour me. How do I know you are keeping your end of the bargain? You do not tell me what goes on in these camps.’

‘Do you wish to make a complaint?’

Kitara remains silent.

‘There are forms you can fill in. You may do so if you wish.’ Smith shifts some papers on his desk, looking for something, and after a few moments holds up a form and waves it at Kitara. ‘But I should tell you, we struggle to process a complaint of the sort you may want to make. Each is processed equally and we require the same set of information. If you wish to complain about the treatment of a person or persons, you have to state their names and their nationalities, and you have neither.’

‘They are citizens of my country; of your country too, some of them.’

‘Your country? No. You require a state to be recognised by the host state for an individual to claim that nationality. Your government appears to have ceased to function, so the basis for that recognition has disappeared. And without a nationality, without the anchor of a state, we can say an individual does not in fact have statehood, and therefore has no legal basis for existence. And if a person does not exist, they cannot be mistreated. There is also no complaint, nothing to file, no paperwork to process. We cannot act in or against a vacuum.’ He throws up his hands. ‘The law is clear. Your country no longer exists, Mr Kitara. The people in these camps are stateless. As such, they are no longer entitled to succour from our nation.’

‘Many of these people were English citizens. Some have married English spouses and had children.’

‘Spouses of immigrants have the option for a quick divorce, in which case they regain the rights of an English citizen, or they can choose to remain with the immigrant and their children and accept the removal of their English citizenship. Children born in England to at least one immigrant parent are considered immigrants too. Their children, though, will be allowed to remain.’

‘Statehood does not cease in times of war. A nation does not cease to exist because there is a change in government.’

‘No. But as a nation, we have the right to recognise the legality of a country, and we choose not to recognise those where there is no rule of law, where one group terrorises another, where there are ongoing genocidal practices. Israel exists because we choose for it to exist. Your republic does not because we choose for it not to exist. But, Mr Kitara, you know all this. You do not need me to tell you this. Are you wavering? Can we still trust you?’

Kitara cannot find the words to respond. Instead he says, ‘I want to be taken to a camp.’

Smith stares at him, half a smile on his face. ‘Do you? Are you sure?’

‘I want to see for myself.’

Smith shakes his head, the smile disappearing. ‘It is a bit late for that, isn’t it?’ Then, ‘Mr Kitara, do not concern yourself. You have chosen the right path, the path of light, if I may describe it as such. You may yet be returned to your homeland a powerful leader, ready to heal, to reconcile your people following in your wake.’

‘May?’

Smith shrugs. ‘It is not my decision. I am simply a messenger. I will say, though – and I say this for your own good – your usefulness has dropped off recently. You must try harder. There is still a war to win.’

‘A war? A war on your own people?’

‘No. Not our war. Yours. I suppose in law the people were once ours but we are giving them back now. Every last one. Only you can lead them back to their homeland, only you can save them.’

Smith takes up his pen and begins writing again.

‘There is one in particular. I want to ask about one in particular.’

Smith looks up. ‘Your son?’ He looks almost apologetic.

Kitara shakes his head and hands over a note with the name and address of Mary’s mother. ‘I ask only that you tell me where she is, what you have done with her, whether she is alive or dead.’

Smith looks at the note, turns it over. ‘Why are you giving me this?’

‘I want to know, and I know you can tell me.’

‘We treat everyone the same.’

‘Look at it. It is the name of the mother of one of my staff. The girl is distraught.’

Smith turns the note back over, shrugs. ‘There is nothing on this paper.’

Kitara pauses. ‘There is a name. An address. You must have records.’

‘I can see nothing on the paper. It is dark in here. Perhaps you imagined a name on there. Or perhaps you handed me the paper thinking it was the right one but without realising that in your haste to get here you had grabbed the wrong paper, a paper with nothing on it.’

Kitara stares at him for a few moments but knows it is pointless to say more. He turns to go, taking back the paper, the name clearly visible.

He is already several paces off when Smith calls out. ‘Wait.’ His tone is softer.

Kitara turns to see him standing, his face illuminated from below by the lamp.

‘I do have another message I have to convey. It is not good news.’

‘Well?’

‘Your son.’

‘What of him?’ Kitara starts to hear the same drumbeat as when he found the note on the newcomer, the same beating in his ears.

‘We had suspected it for a while but it was confirmed recently. He was one of the leaders, if not the leader, of the opposition forces in the Republic.’

Kitara is still.

‘It is hard to find out these things in such times. It used to be much easier. It seems he came out of nowhere. I mean, he had all the credentials, the family connections – his mother, I mean – but he was very young and we had no intelligence on him until very recently.’

Kitara hears the word ‘was’. He knows what it means but cannot address it, cannot address its meaning. ‘No. Not Joseph. You have the wrong person.’

Smith shakes his head. ‘There is more.’

Kitara knows what is coming. He wants the man to be quiet now, to stop, to stop talking.

‘Your son is dead.’

He hears water dripping from the roof of the tunnel.

‘It happened several weeks ago, though I am unable to tell you where or exactly when.’

‘How do you know?’ The words come quickly.

‘What do you mean?’

‘How can you be certain it was him? You were not there.’

He shrugs. ‘It takes longer these days. But we get there in the end.’

Kitara turns away, looks up at the ceiling, trying to find the source of the water.

‘It appears he was murdered. We believe he was killed because of infighting in the opposition ranks. A struggle over leadership.’

Kitara shakes his head. He has questions, so many questions, but they are unformed: a mass of words.

‘This is hard news to bear, Mr Kitara. But the best way of ensuring he did not die in vain is to do what we say. You can save these people, save them in his name if that is what it takes.’

Kitara’s legs do not move. The tunnel is silent, save for the drip of water. He now hears only this, the water dripping steadily onto the platform. He wants the noise to stop. He finds he wants to put his hands over his ears, push his thumbs into his earholes until it stops, and push and push until finally he breaks all the little bones inside his skull.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Alastair Bruce Book excerpts Book extracts Penguin Random House SA The Weight of Skin