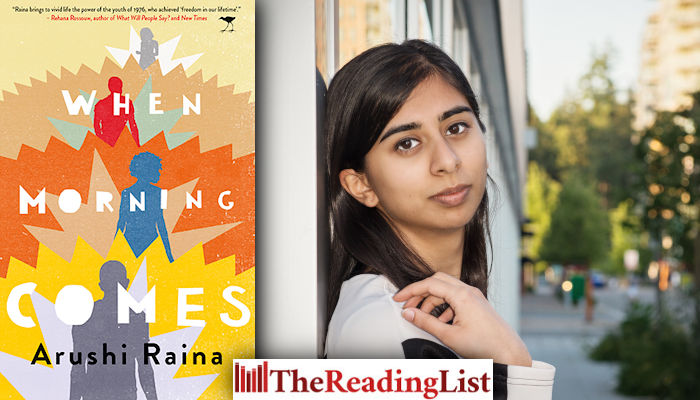

Read an excerpt from Arushi Raina’s debut novel, When Morning Comes – a snapshot of South Africa on the eve of the Soweto uprising

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Arushi Raina’s debut novel, When Morning Comes.

About the book

It’s 1976 in South Africa.

Written from the points of view of four young people living in Johannesburg and Soweto – Zanele, a black female student organiser, Mina, of South Asian background working at her father’s shop, Jack, an Oxford-bound white student, and Thabo, a tsotsi – this book explores the roots of the Soweto Uprising and the edifice of apartheid in a South Africa about to explode.

In Soweto, Zanele, who also works as a nightclub singer, is plotting against the apartheid government. The police can’t know. Her mother and sister can’t know. No one can know.

On the affluent white side of town, Jack Craven plans to spend the last days of his break before university burning miles on his beat-up Mustang, and crashing other people’s parties.

Their chance meeting changes everything.

Already a chain of events are in motion: a failed plot, a murdered teacher, a powerful police agent with a vendetta, and a secret network of students across the township. The students will rise. And there will be violence when morning comes.

Introducing readers to a remarkable young literary talent, When Morning Comes offers an impeccably researched and vivid snapshot of South African society on the eve of the uprising that changed it forever.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Meena

To make sure no one mistook him for a terrorist or a communist, Papa had a picture of President Vorster in his shop. Vorster had a dreamy look on his face. His eyebrows were thick, his chin lumpy. At the other end of the shop, above the women’s personal care shelf, there was a bad print of a Ganesh painting framed by a garland of fake marigolds. My grandmother had insisted on it.

Papa had not always been so eager to show his support for the government. When he was twenty, he’d been arrested for sitting on a whites-only bench with some of his friends as part of a political protest. They had waited hours for the police to come.

Papa spent two days in jail before his father paid his bail. Then he returned home with his father and went on making shoes as they always had. No more protesting. At least that’s the way my grandmother told it to me. Papa never told me the story himself. My grandmother always ended the story with the admonition she’d given to Papa at that time: ‘Remember to be grateful for what you have, Meena. You might have been black.’

From the outside, things hadn’t changed much since then. Five minutes in that direction was Soweto, and blacks still came through here to get to the white parts of town. But there was something angry about our black customers now. The way they came in, ignoring the blacks-only entrance and slapping their change on the counter, made Papa nervous. He never said so, but I knew.

It was a few months ago, near Christmas. We were closing up shop and I had gone round the back to check on the rubbish. The water was running down the street, dirty and cold, getting into my shoes. And there was a boy there in a blue coat standing by the gutter and the row of dustbins, smoking.

Then he was gone. I walked over, wondering why he had been standing there like that when it was so wet. I looked down. On the ground, where the boy had dropped his cigarette, there was a pamphlet. I picked it up. On its cover was a black fist. The SASO. When I lifted the lid of our dustbin to throw it away, I saw more pamphlets, from the ANC and PAC – organisations that were banned.

I could have handed them over to the police. But I lifted them out and hid them in the shop.

Papa had opened the store in 1971. To have a shop in this area, he’d had to find a white man to sign that he owned it, a shadowy ‘Mr Hendriks’ who was referred to my father by a friend. This Mr Hendricks would not meet Papa in person, but he’d sign the papers. Apparently he had no problem with Indians, as long as you paid him.

When the signatures had been approved, Papa was overjoyed, the happiest he’d been since Mama died.

The store was five years old now and still smelled of paint even though we’ve been lighting incense every morning since.

Five years, and the first time a policeman came into the store was yesterday, a few weeks after we’d doubled our order of instant coffee and coal. A black Mercedes drove up and the policeman came out while the black driver stayed in the car with a blond man in the back. The policeman stopped at the shop door and the bell rang. He stared at the radio, which was playing a concerto. Then at the garlanded picture of the elephant-headed god.

It was winter, but I could see the sweat on his neck and how his shirt stuck to his body. Slowly, I slid the pamphlets I was reading into my maths book and closed it. The policeman was watching me. I put my fingers over the maths book, and waited.

Papa was upstairs but I didn’t call to him.

The policeman walked up to the counter and put his hands on its plastic surface, first one then the other. Then he sniffed.

‘What is this smell, hey?’ he said.

‘Sorry, Meneer?’

‘This smell, this disgusting smell.’

I looked back at the policeman with the blankest expression I had. He leaned down so we were eye-level – I smelled sweat, saw pieces of tobacco in his teeth.

‘Get me a packet of Lucky Strike,’ he said.

I turned around, leaving the maths book on the table. Its cover propped open, slightly. Lucky Strike, he’d said, even though he was a tobacco chewer. Lucky Strike, I repeated to myself, just so I didn’t panic. It was strange they’d sent the policeman to fetch the cigarettes, and not the black driver. Why had they done that? My hands slipped over the packs, and they tipped off the shelf. They made a soft crackling sound as they dropped to the floor, one after the other.

‘What the hell did you do?’ the policeman said. ‘I asked you a very simple thing.’

I stood up with a pack in my hand. He snatched it from me and threw coins that fell onto the floor. Then he left.

‘Incense sticks,’ I said to the empty shop.

The policeman leaned into the car and passed the cigarettes to the blond man. Then he got into the back seat, and the car slid away from the curb.

Why was there an unmarked police car going through here? I didn’t know then that I’d see the blond man again. But I should have guessed. I had a collection of illegal pamphlets. I was asking for it. The picture of Vorster could only do so much.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Arushi Raina Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media When Morning Comes