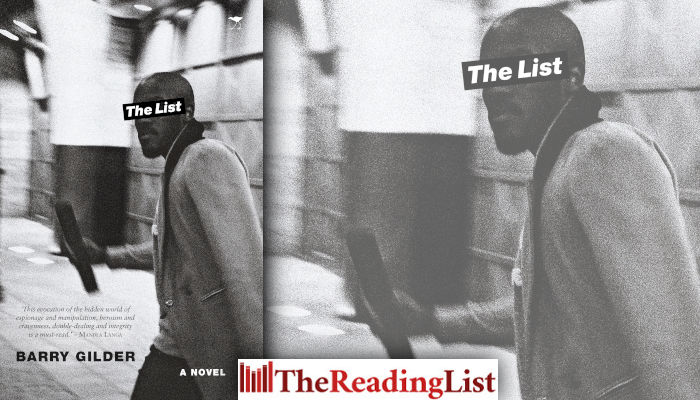

‘Some of us still wear our struggle names like war wounds’ – Read an excerpt from Barry Gilder’s debut novel The List

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Barry Gilder’s debut novel The List!

April 2020

I tell this story now in the knowledge – sound, I’m sure – that the telling is too late. Too late to go back. Too late to tell it again, differently … I tell this story now because I was there. Because I am safe now – relatively, anyway – and once more in drizzling London, an obscure survivor.

Although conceived and birthed well before the ANC’s December 2017 elective conference and the changes of the guard that ensued, The List imagines a ‘New Dawn’ for South Africa in the closing years of the 2010s. But is it dawn or dusk?

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from The List:

~~~

Chapter 5

June 2019

Sandile Ndaba was not – in any sense of the word, he felt – mystical or reductionist, destined to be South Africa’s minister of intelligence. He was not born to the calling. It was not by any means a career choice. It was certainly not an ambition. His aspirations had lain elsewhere. If at all for high office, it should at least have been one in which he could make life better for his people. He had much preferred, in spite of the lesser rank, his previous term as deputy minister for social development. Now, with his return in 2016 from his second exile as ambassador to France, a posting precipitated by his fall from grace when his party tore itself asunder in 2007, he came home to a moment of renewal.

The dramatic reduction of his party’s majority in the 2016 municipal elections and the loss of key cities had been the necessary dose of good old-fashioned shock therapy. At its national conference in 2017 a new leadership had been elected. And he, emerging from the shadows so to speak, was elected back onto the national executive committee. And thus, with the general election a few months ago, his name back in a respectable spot on the electoral list, a new president, a new cabinet, circumstance and history had brought him to this point, a point he suspected was going to test the limits of his integrity and resolve, for – in spite of the renewal of the party – things still did not sit easy in the country.

~~~

In spite of his speculation on the hidden purpose of this call, and his slight discomfort at the formality now required of his relationship with Sandile, Vladimir Masilela crossed the carpeted floor of the eighteenth-floor office of the Plein Street ministerial building to give Sandile the three-part hug and the whisper of an ancient greeting. He took in once more the minister of intelligence’s office with its 180-degree view of the parliamentary precinct and Cape Town and its harbour beyond. He took the seat offered to him on the sofa, at right angles to the chair into which Sandile lowered himself. The personal assistant hovered at the door.

‘Good of you to pop in, Mr Masilela. I didn’t realise you were in Cape Town. Always good to see an old friend. I don’t have much time, I’m afraid.’

The minister nodded at the personal assistant who backed out the door.

Masilela lifted his face to Sandile, smiled with one side of his mouth and spoke just as the assistant paused at the door to close it. ‘It’s good to see you, Minister. I thought that, while I’m passing through, I should pop in to congratulate you personally.’

Masilela leaned forward to help himself to coffee. He looked up from over his spectacles at the minister and offered to pour him some.’No, no, Comrade Vladimir, but you help yourself. I’ve already had. Was with the president just now, in a meeting with the Americans. He read them the riot act. Go ahead.’

Masilela poured his coffee to the lip of the cup, took the sweetener dispenser and allowed one tablet to drop in, then stirred for some time, his eyes fixed on the hypnotic micro-whirlpool in the cup. He was about to speak when Ndaba raised his palm, lifted his eyes to the heavens and shook his head.

‘How are you, Comrade Vladimir? You still use that name? After all this time?’

‘I’m good, Sandile. Yes, I do. So do you, don’t you? You weren’t born Sandile.’

‘Ha! Yes, I do. Except when I go back to my village. They still call me Jabu.’

Ndaba stood up, took the long walk back to the desk, unlocked a drawer and slipped something into the pocket of his jacket. ‘Com, I know you told me the story in one of our drinking sessions in Lusaka, but remind me how you got your chimurenga name. Me, I took mine from the uncle who introduced me to ANC politics when I was a boy.’

‘Well, when they asked me to choose an MK name when I got to Maputo, I immediately said “Vladimir Ilyich”. I assumed it would betaken, but surprisingly it wasn’t. The “Ilyich” has fallen away.’

Ndaba shifted in his chair. ‘And people don’t complain that you’re not using an African name?’

‘Yes, some do. But I’m proud of my name. Some of us still wear our struggle names like war wounds that prove we were there. But, what did you want to—’

Ndaba held up his hand, then put his index finger to his lips and raised his eyes to the heavens again. Masilela looked up as if expecting to see someone staring down at them. Sandile leaned forward, refilled Masilela’s coffee cup and slipped a folded piece of paper under the saucer.

‘Yes, Comrade Vladimir, the chief gave the Americans a hard time. It was a speech I wish we could make public. Told them that after twenty-five years of democracy, we had not moved far enough, nor fast enough. It was time for decisive action and time to stop kow-towing to international pressure to moderate our economic programme to their neoliberal views. Well, he didn’t use that term, but the message was clear.’

Masilela dropped another sweetener into the cup. He thought he knew now what was going on. Or at least what was not going on. If he had been called in to be asked to come back into the Service, there would be no need for this subterfuge. He would need to be patient to hear why he had endured two plane trips and the probable ire of Doreen to heed this sudden call.

‘Yes, com, he told them that we are going to follow India’s example of manufacturing our own cheap generic medicines, and that they should please keep their pharmaceutical dogs at bay, and that we are going to renew our independent views in multilateral forums, will not support their interventions in Africa and the East. We will intensify our campaigns for a fairer world trade dispensation, a reformed UN system.’

Masilela kept his eyes on the minister, flicked the teaspoon from his saucer and let if fall to the floor; he bent to pick it up and unfolded the piece of paper, read it between his ankles. He offered occasional sounds of interest and agreement.

Thanks for coming. Sorry for the ambush.

We can’t talk here.

Meet me for dinner tonight at 7:30.

Blues in Camps Bay.

I’ll be sitting inside, right at the back.

Masilela sighed. There was no chance of a return flight tonight. He would have to check into a hotel and find a good excuse for Doreen regarding the kids. He looked up, smiled and nodded, then shrugged his shoulders in vague capitulation to whatever deep secret this old comrade and friend and new minister so carefully guarded. He was tired of secrets. Molecular infestations of the mind that clogged the pathway between self and world. Secrets required a persona that held itself remote from the interactions around it. They manufactured an inner world that at times seemed more complicated, more populated than the outer.

‘Yes, Comrade Vladimir, things are different now. Things are changing. The chief is not like his predecessors. And he has the support of the NEC, a good bunch of comrades – experience and freshness and, yes, a better record of integrity. He has some radical ideas for setting an example, for combatting inequality. But you will have to wait to see. He will announce soon. And, tell me, how is retirement? I believe you refused an ambassadorial post?’

‘Yes, Minister. Good. Retirement is good. Doing a lot of reading, some writing. Spending time with the kids and seeing old friends and comrades from whom work pressure kept me away for nearly twenty years. Yes, I declined the posting. I needed a break from government. Maybe later, when … if … I get bored with retirement.’

Sandile rose from his chair, moved over to the desk and lifted the phone. ‘Mr Masilela is leaving now. Give me a few minutes before my next appointment.’

Masilela stood, smiled with some sorrow, and put out his hand for the treble handshake. The assistant returned silently to the room.’Thank you, Mr Masilela. Very good to see you again. Perhaps we can meet socially if you are in Cape Town for a while.’

Ndaba made his way over to the desk, lowered himself into his chair, took a file from the in-tray and looked up with a last smile and raise of the right hand to the forehead in pale imitation of the MK salute.

‘I’m pretty sure, Comrade Vladimir, that I’m under surveillance.’

By way of emphasis, and perhaps to draw a crisp border between idle dinner conversation and real business, Sandile pushed forward his plate now emptied of everything except the prawn shells and the uneaten green peppers. He lifted the glass of wine to his lips and looked at Masilela, wrinkles appearing at the corners of his eyes as if he were looking into a bright light. His face a darker shade against the purple velvet of the booth. Masilela’s plate had long been set aside, leaving no trace apart from a convoluted pattern of leftover juices of the pepper steak and potato wedges. He poured himself another glass of wine. He closed his eyes for a moment, partly to escape Ndaba’s stare, but mostly to draw his own frontier between banality and the thing that was now to come.

With eyes closed, other senses usurped consciousness. The sounds of subdued conversations, the clatter of cutlery on crockery, the whiff of delicately grilled meat, steaming vegetables, catch of the day, all a background score to the quiet drama at their table. And beneath it all the tactile rumble of the sea as waves broke against Camps Bay beach below. He opened his eyes and looked around for any nearby diners worthy of operational note.

‘Why, Sandile?’

Sandile took his phone from the breast pocket of his dark blue suit; the phone from which he had removed the battery just as they had sat down to dinner. He reinserted the battery, switched the phone on and stared at the screen. He pressed some keys, frowned, removed the battery again, replaced the phone and returned his eyes to Masilela’s. ‘Why am I being followed or why do I think I’m being followed?’

Masilela tipped his glass. ‘Both, I guess.’

‘You forget I was also trained in Moscow – skills I actually haven’t had to use for a long time, until now, this job.’

‘But why, Sandile? Who?’

‘Who? Well, for one, I suspect the bodyguards the Service assigned to me. That’s why I gave them the slip tonight. But who knows? The Service, the Hawks, some private entity?’ Sandile filled his glass. ‘Dessert?’

Masilela looked around for a waiter. They were all otherwise occupied. ‘Later perhaps. But on whose behalf?’

Sandile waved his hand in the air without turning from Masilela.’On whose behalf? The coalition of the de-captured is my best guess.’

‘The what?’ Masilela didn’t notice the hovering waiter until Sandile’s face turned away from him. He ordered ice cream and hot chocolate sauce, Sandile the crème brûlée. He poured more wine for Masilela, waved the empty bottle at the departing waiter.

‘The coalition of the de-captured. It’s obvious, Vladimir: those in the party, the state, businesses captured by the corrupters ousted at the 2017 conference. We always said, didn’t we, that they wouldn’t give up easily?’

‘I guess, we did. But are they all ousted? You sure of that?’

‘Ha! That’s why you’re here, Vladimir. That’s why I called you.’

The waiter returning with the bottle of wine allowed Masilela a moment to process this. As he observed the ritual of the proffered label, the nod, the deft removal of the cork, the pouring of the taster, the swirling and holding up to the light, he struggled to fathom what his role may be in this scenario of surveillance and de-capture. He watched the back of the departing waiter. ‘You know, Comrade Sandile, when you called me so urgently to Cape Town, I jumped to the conclusion that you were going to recruit me back into the Service.’

‘Ha, Vladimir! Would you have accepted if I had?’

‘I spent most of the trip composing a “no thank you” speech.’

‘Well, no, Vladimir. I do need to change the Service leadership soon. I really don’t trust this Brixton fellow.’

‘You shouldn’t.’

‘Shouldn’t what?’

‘Trust Brixton Mthembu. I don’t.’

‘Good. We agree. And, yes, it would be good to work with you again. We go back a long way and going back a long way brings trust. But this thing I called you for is even more important.’

‘More important?’

‘Yes, more important. Strange things are going on. Very strange.’ His eyes scanned the room for the waiter and he raised his hand, palm up. The waiter nodded and rushed back to the kitchen. ‘You know, Vladimir, President Moloi has hardly been in office a month and there are already calls for his recall, from factions or forces … well, we don’t know really where they come from.’

The waiter arrived with the desserts. Sandile picked at his brûlée while he explained the mission to Masilela. And he did so just as they had been trained to: clearly articulating the overall mission, the objectives, the battlefield conditions, the nature, strengths and weaknesses of the enemy, of own forces, the resources at hand, the constraints, the operational conditions. Masilela listened, raising his eyes now and then from the ice cream, sucking on the spoon, eyes widened. He felt as if he should be taking notes, an old habit not appropriate now, so he conjured up a mnemonic for each distinct point that Sandile made. At last Sandile went quiet and turned his attention to the remains of his dessert.

‘You done, Minister?’

‘Yes, Masilela, I’m done.’

‘Hell, Comrade Sandile, this is tough.’ Masilela poured himself more wine. ‘You are asking me to lead an investigation without the resources of the Service, without the knowledge of the Service, without the knowledge of anyone apart from you, and my team, and the president, of course. Shit! That’s all I can say. Excuse my language, Comrade Minister.’

‘I’m afraid so, Vladimir. That’s about it. I’m sure you understand there is no other way. We can’t use the Service. Some of the people we’re worried about are there. And we are traversing tricky ground – people’s reputations, lives are at stake, and, of course, the future of our postponed revolution.’

‘But where do I start?’

‘Hey, Vladimir! I called on you because you’re the one person the president and I could think of who would know where to start.”But I had resources before … The whole of the Service – agent handlers, analysts, surveillance teams, technical resources, the works. We even had better resources than you’re offering me now when we were in exile.’

‘You’ll start with The List.’

Masilela put down his glass.

‘The List? Which list?’

Sandile drained his wine. ‘Mandela’s list.’

‘Mandela’s list? The one the boers are supposed to have given him of their agents? We have it?’

Sandile reached into the inside pocket of his jacket and removed a roughly rolled sheaf of papers that had caused an incongruous bulge in his otherwise trim apparel that Masilela had not failed to notice. He had assumed that the minister, having eluded his bodyguards for this assignation, had been carrying a firearm. He took the papers Sandile passed him under the table and, having no suitable pocket in his Madiba shirt, slipped it into the front of his slacks and let the shirt fall back over them. The document pressed against his groin with a discomforting presence.

‘Treat the list, Vladimir, with circumspection, as you know. Ignore, of course, the ones who are late and those who are out of active politics, except of course if they may lead to others still involved. We’re only interested in those who are still active in the party or government or related organisations, maybe even in business if they wield influence.’

Masilela weighed the doubts in his mind, like a juggler tossing flaming torches through the air, but aware that, in the very momentum of the circling torches, there is an inescapable constant – the obligation to catch. Once again he had got the call. It had come many times in his life and he had always been compelled to answer it. Yes, he had turned down an ambassadorial posting and the call to stand for the new national executive; these were calls that others could answer to. But this one depended on the specificity of him.

And so he agreed, indicating his consent by raising his glass to Sandile and draining it in the hope that it would bring their meeting to a close. He needed to think, to readjust his life, to develop a back story for family, friends and comrades that would explain his sudden trip to Cape Town and much of the unexplainable that would follow.

‘What about your team, Comrade Vladimir? Any ideas yet?’

‘Only one, for now – Comrade Jerry.’

‘Jerry?’

‘Jeremy … Jeremy Whitehead.’

‘Of course. Good choice. You trust him?’

Masilela laughed. ‘Trust? Trust is a spiral staircase leading from a basement to a penthouse.’

‘Huh?’

‘Yes. In the basement is distrust. Actually, there is a level below that, a second basement: hatred. Distrust is still relative – you are not sure, but once you know someone is impimpi you simply hate them.’

‘Whatever their reason for selling out?’

‘The act of selling out is absolute. The reasons might be relative.’

‘Okay. And after the basement?’

‘Ground floor: tolerance.’

‘Tolerance?’ Sandile scratched his nose.

‘Yes, tolerance. You know you can’t really trust someone but circumstance dictates that you tolerate them. Like we had to do with the boers in the Service when we amalgamated.’

Masilela picked up the wine bottle, held it to the light, tipped it over. It was empty. ‘Next comes acceptance. You have no concrete reason to doubt someone so you accept their bona fides until proved otherwise.’

‘And next?’

‘Friendship.’

‘Huh? How did friendship get onto this staircase?’

‘Friendship is close to the penthouse. I mean real friendship, when you share intimate things, like you and I had in those Lusaka years. You don’t believe that someone like that could be impimpi.’ Masilela began to peel the label off the bottle. ‘But, you and I know … We have had friends who turned out to be sell-outs. That is the worst betrayal. Those are the ones who descend to the second basement.’

Sandile folded his napkin. ‘So? Which floor is Whitehead on?’

‘Same as you, chief. Friendship. Just below the penthouse.’

‘I see. Neither of us has reached the top. What do you have to do to get to the penthouse?’

‘Die.’

‘Die?’ Sandile’s eyes widened.

‘Yes, the highest form of trust is death.’

‘Death?’

‘Yes, you know you can trust someone who has given their life to the cause.’

‘Vladimir, you should write a book on trust. Thanks for that. So, Jerry is in. What’s he doing now?’

‘He’s retired, like me. Doing some writing, he says.’

‘Anyone else?’

‘No, not yet. I’ll have to think about it. I’ll approach Jerry first and discuss possibilities with him. Maybe his wife, Bongi. She’s in the Service, a manager in analysis. She could get us access to Service information.’

‘Yes, I know Bongi. Good. Keeping it in the family?’

‘Well, not consciously.’

Sandile called for the bill. ‘The List is just a start, Vladimir. I’ll arrange access for you to the Green House records.’

‘Huh? We still have them? Where are they?’

‘They’re safe. Don’t you worry. They’ve been kept all these years out of the state or Service archives, or the ANC ones at Luthuli House or Fort Hare. Perhaps we anticipated a day like this.’

Masilela’s response was interrupted by the waiter returning with the bill. Ndaba started to take out his credit card, then slipped it back and took out cash – a lot of it. Masilela smiled. Ndaba reached into his pocket again and handed Masilela a bulky envelope.

‘There, that’s the refund for your flight and accommodation.’

~~~

On the drive in the hired car back into the CBD, Masilela stuck to the coastal route; it was not the quickest, but passed through Clifton, Bantry Bay and Beach Road through Sea Point. He turned left at the lights near the lighthouse and continued on to Mouille Point. He stopped the car and parked opposite the apartment block where he’d had his director-general’s flat when he was head of the Service, for those frequent trips from Pretoria to Cape Town when parliament was in session.

Masilela climbed out of the car and walked over to his old spot overlooking the rocks below and the sea beyond. He had come here often during those days of high stress, just to think. He stood at the railing, arms stretched either side of him and hands clasped on the cold metal. Behind him the lights of the darkened city shimmered, with more garish lighting offending the night from the Waterfront mall just this side of the breakwater. The sea was too dark to see the breaking of the waves. But they came to him as an oscillation of light and dark, a deep arrhythmic roll and crack of water against rock. He breathed in. The scent of the sea mingled with car fumes and rotting seaweed.

As he stood there, eyes closed, the southeaster suddenly arose, blowing hard, whistling through the buildings and bending the trees along the embankment.

His hands tightened on the railings. He leaned forward.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Barry Gilder Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media The List

Related

- Join Shameez Patel for the launch of her new romcom Next Level Love in Cape Town (27 Jan)

- Listen to an excerpt from Cursed Daughters – the glittering follow-up to the award-winning bestseller My Sister, the Serial Killer

- Don’t miss the launch of To Sharpen Our Senses and Soften Our Touch by Chris Soal at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery (13 Dec)

- Embark on an extraordinary culinary adventure – and get your copy of JAN Voyage signed by Jan Hendrik van der Westhuizen in Cape Town (10 Dec)

- [Listen] Is Paul Mashatile suitable for the highest office? Listen to the new episode of Pagecast – out now!