How Converse All Stars have been appropriated by white people: Read an excerpt from Sorry, Not Sorry by Haji Mohamed Dawjee

More about the book!

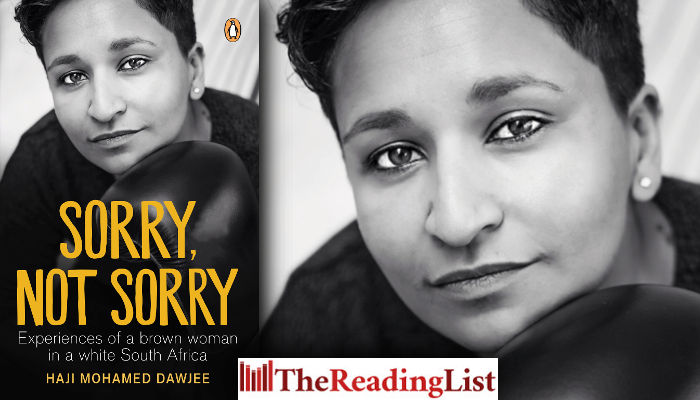

Penguin Random House has shared an extract from Sorry, Not Sorry: Experiences of a Brown Woman in a White South Africa, the new book from Haji Mohamed Dawjee.

In Sorry, Not Sorry, Dawjee explores the often maddening experience of moving through post-apartheid South Africa as a woman of colour. In characteristically candid style, she pulls no punches when examining the social landscape: from arguing why she’d rather deal with an open racist than some liberal white people, to drawing on her own experience to convince readers that joining a cult is never a good idea.

Read an excerpt from the book, in which Dawjee explains why Converse tekkies are not just cool but a political statement to people of colour:

Don’t touch me on my tekkies

Do you know what ‘can’t gets’ are? They’re one-of-a-kind, unique, special-edition sneakers that no one else has, because you just can’t get them. To me, ‘can’t gets’ are more than a single release of a shoe. My personal sneaker-Everest, my ‘can’t gets’, are Nike Air Jordans. My friend Stephie and I often joke that one day when we get a pair of Jordans, we’ll have made it in life. Every now and then I send her a picture just to remind her that the dream isn’t dead. There’s a pair of size fours out there waiting for us. And one day, we’re going to walk into a store and drop cold hard cash on the counter without feeling guilty about where that money should have gone and we’re going to walk out with our ‘can’t gets’.

It seems like a small, fickle goal, but it means everything. It’s ambition, it’s pride, it’s having what you could never have and knowing that you’re going to have it because you earned it. A lot of people don’t understand that. Do you know how many times I get asked why expensive sneakers are so important to brown people? Because there comes a point in time when things like sneakers can be important. There comes a point when our feet deserve to wear the nice things our eyes stared at as kids. Don’t touch me on my tekkies.

There’s a recipe for washing white Converse All Stars. First, you need a bucket filled with warm water and some bleach – the kind that doesn’t make the colour run. Add some washing powder and mix it all up. Give it a good swish so the powder starts to bubble. Then soak your shoes. Once the water has penetrated the canvas, grab an old-fashioned, dependable bar of green Sunlight soap. Scrub one shoe at a time using a small nailbrush so you can get between the grains of the laces and that hard-to-reach place where the rubber sole meets the shoe. Concentrate on one area at a time.

I usually start at the toe then work my way around the border of the shoe before lathering a healthy dose of soap on the under-side and giving that a good scrub as well. All the while, the hand not doing the scrubbing is balled in a fist inside the shoe. Then I focus on the canvas. I scrub each side repeatedly, re-soaping each time. Once the sides are done, I undo the laces and give the tongue a thorough scour. After each helping of soap and the working of each patch of canvas, it’s important to dip the shoe into the bucket to get rid of the green remnants of soap. There’s always a danger that the tinge will stay behind if you don’t. Once you’re done, leave the shoe in the same bucket for what I like to call a ‘safety soak’ and start on the other one. When both shoes are spotless, leave them in the bucket to marinate while you work the laces methodically in much the same way.

Use your index finger and thumb and run them up and down each lace while it’s soapy to make certain you get an even spread of suds, then pop them in the bucket as well.

While the laces soak, go ahead and give your shoes a rinse. Squeeze the soap out and rinse repeatedly until the remaining water drips clean, then slap the shoes together to shake off excess moisture. You can dry the shoes and the laces separately, or lace up and dry in a composed fashion. My preference is for the latter.

And now, here’s the ultimate secret to maintaining pristine whiteness: give the shoe a liberal dusting of baby powder (the more expensive option), Maizena (the mid-range option) or plain old mielie meal (the classic option). Massage your powder of choice into the shoe, including the rubber trimming. Make sure to get it into the important seam areas and then leave your All Stars in the sun to dry. A word of warning: if you’re using mielie meal I recommend drying your tekkies in the shade. The sun may turn the powder yellow and this can stain and ruin the shoe.

There are two reasons for maintaining the pallor of your white Converse All Stars. One: it always looks like you have a new pair of shoes. Two: longevity. If you take care of your All Stars properly, they remain wear-ready and comfortable for ages, preventing additional spending on new shoes for years to come.

The longest time I have ever kept a pair was twelve years. That pair was navy blue, but I followed the same cleaning recipe, minus the bleach, of course.

It was a sad day when I had to replace them. They saw me through both undergrad and postgrad degrees. They walked me in and out of school at my first real job. They dragged me through Europe and a couple of places in Asia. They saw Everest from the hills in Darjeeling and sweated their way through Goa. They trudged their way across the cobbled paths of Nottingham when I worked in a store – illegally. That pair of shoes journeyed across twelve years’ worth of my life experience. They followed more roads than a global nomad and kicked the sand and grass in more parks than a ranger.

Until I had to replace that pair in December 2016 I never paid more than R200 or R300 for Converse. You can imagine my shock and disappointment when the new pair cost me R700. Then it struck me: Converse is the shoe equivalent of gentrification.

Tsotsi shoes. That’s what they used to call Converse in white communities. I cannot count the number of times teachers commented on my feet when I wore them to civvies days. They told me I shouldn’t wear them because they were the shoes of criminals. Converse were never white people’s shoes. In their eyes, Converse All Stars were the shoes of the other and that’s exactly what they saw every time they turned on the television or took a wrong turn on their way to safe suburbia. And with the sight of these shoes on the wrong feet, came all kinds of tsotsi conclusions.

To us, these tekkies were never a problem.

Converse All Stars were not tsotsi shoes. They were the symbol of a lifestyle; Converse meant you belonged to a certain community. And if you took care of them, you always had something to be proud of, no matter what. They were top of the range when compared to other tekkies at the time, but still relatively affordable. And the extra rands were worth it because of the shoe’s quality and the length of time you would be able to wear them for.

To us, these tekkies were never a problem.

And they weren’t a problem to the white person until they entered their communities on brown feet. Then all that changed. The tekkies started showing up in suburbs, they started showing up in places where there were hardly any people of colour. The rock clubs, the skateboarding communities of Cape Town, the coffee shops of Parkhurst … You get the idea. In the past, I would enter these environments and get nothing but judgemental stares. Then things changed. The culture of Converse changed. The vibe changed.

To white people, these tekkies weren’t a problem. Any more.

The best way to destroy part of a culture, even if that part is as material as a pair of shoes, is to take it from its people.

The power of white people to take things never dies, but our ability to access the things that once belonged to us suffers endless extinction. Even as a middle-class person of colour, R700 is a hefty price to pay for a pair of shoes that saw me and a generation before me through life. And now we pay the price of a people who have always wanted us to do the things they want us to do in order to be accepted. Not recognised. Just accepted. In other words, it’s now acceptable for people of colour to wear All Stars because white people wear them, while the rightful owners of that trend go unrecognised.

Globally, a sneaker is more than a sneaker. This special breed of footwear stretches beyond its athletic purpose. It is an ideology. It conveys an identity, a class, a race. It has meaning. It has method. And the status of tekkie culture is no different in South Africa. The tekkie is a canvas for a specific, politicised point of view. The Converse All Star tekkie was a specific, politicised point of view.

But its canvas has been washed clean with the brush of plain old shallow fashion. Appropriation. The surface of the shoe demarcated and declared gentrified. Its meaning forgotten. Its space occupied by something else. The Converse All Star’s political point of view has been silenced by white feet. No more will the shoe share a dialogue with people of the same community, who often had to whisper their thoughts to each other. A certain type of tekkie, like the All Star in South Africa, is a magnet that both draws a people together and sets them apart.

Our people were the progenitors of the Converse All Star. Our people. The kind of people who grew up in the designated locations of the Group Areas Act. It was the shoe of choice for the economically deprived. Selected because of its functionality, comfort and durability. Selected because of the sense of pride that came with all of that. But now, tekkie culture and its growing popularity on the other side of the privilege border create a further political divide – a culture war of sorts, between those who work hard to own and those who can afford to just … take.

A sneaker is not just a shoe. It’s that point where childhood desperation and adult aspiration meet. It’s where those two qualities kiss and touch and promise to become something new. A sneaker is not just a shoe. It is the difference between wanting and having. It is the running towards something instead of running away. A sneaker is not just a shoe. A sneaker is the difference between having and craving. It’s that silent play that happens in your heart when it speaks of getting the things you need versus getting the things you want.

Philosophers have teased us with a riddle through the ages: if a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear, does it make a sound? The riddle is an existential conundrum that can and has been massaged into many meanings, the most popular being that sound is a product of the ears. If ears are absent, so is the sound.

But let’s try another angle: that the riddle’s main question is not about sound, but rather about loss. The loss of meaning. The loss between what something is and how it appears to be. And to many, that is the most important topic that can be extracted from this conundrum. The discord between the perception of something and how it really is. It’s the difference between wearing shoes and wearing a declaration, and understanding the difference between the two. The meaning of something does not cease to exist just because someone is unaware of it.

A sneaker is not just a shoe. It is a statement. Is anyone listening?

When a tekkie shouts, will you know what it’s saying when you don’t bother to understand its language?

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Haji Mohamed Dawjee Penguin Random House SA Sorry Not Sorry

You must log in to post a comment

does this apply to only people who live in south african or the US too! because if it does i’ll have to get different shoes other than my converse, i don’t want to approbation anything . **appropriate sorry lol.

bones!!