Revealing the kind of ruler Nicholas II believed himself to be: Read an excerpt from Last of the Tsars

More about the book!

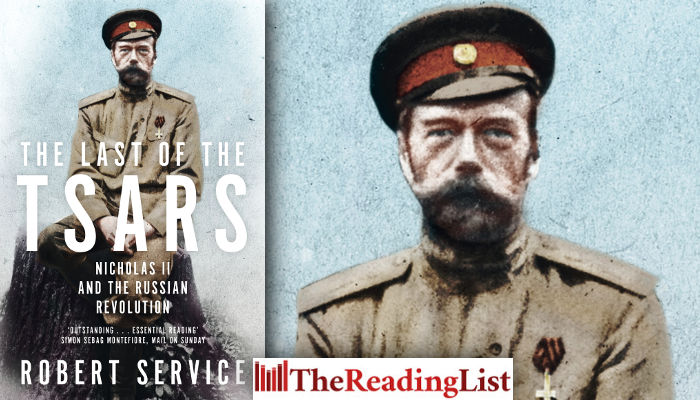

Pan Macmillan has shared an excerpt from Last of the Tsars: Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution, the new book by Robert Service.

In March 1917, Nicholas II, the last Tsar of All the Russias, abdicated and the dynasty that had ruled an empire for three hundred years was forced from power by revolution.

Now, on the hundredth anniversary of that revolution, Robert Service, the eminent historian of Russia, examines Nicholas’s reign in the year before his abdication and the months between that momentous date and his death, with his family, in Ekaterinburg in July 1918.

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from Last of the Tsars:

1. Tsar of all Russia

In 1916 a grand ceremony took place in wartime Irkutsk, the great Siberian city south of Lake Baikal, at a time when the Great War was exacting its dreadful toll in lives on the Eastern and Western Fronts in Europe. The purpose was to raise morale in that out-flung region of the Russian Empire. It had been twenty-five years since Nicholas II had visited Siberia when he was still only heir to the throne of the Romanovs and was finishing a global tour that had taken in Vienna, Trieste, Greece, Egypt, India, China and Japan. To commemorate that visit, Governor-General Alexander Pilts gave a keynote speech to the Siberian dignitaries in which he commended the bravery of the imperial forces: ‘At a recent audience with our Sovereign Emperor, he kindly told me: “As soon as the war is over, I’ll gather my family and come as your guest to Irkutsk.”’ The audience greeted the announcement with a loud hurrah. It was a remarkable fact that no ruling emperor had come to Siberia since its conquest by Russian traders and troops around the end of the sixteenth century. Siberians high and low felt unloved and neglected, and loyal inhabitants looked forward to a visit by Tsar Nicholas and his family.

No one could know that, in less than a year, he would be returning to Siberia not as the ruling Tsar of All Russia but under arrest as Citizen Romanov. He who had dispatched thousands of political prisoners to Siberian forced labour, imprisonment or exile would himself be transported to detention in Tobolsk. Thrown down from power in the February 1917 Revolution, he and his family would be held under strict surveillance in the little west Siberian town that, by a twist of fate, possessed one of the empire’s largest prisons, although the Romanovs were spared the unpleasantness of being locked up inside its walls and were instead confined to the provincial governor’s residence. The Bolsheviks overturned the Provisional Government in the October 1917 Revolution and after a few months transferred the imperial family to Ekaterinburg, their power base in the Urals, while they considered what to do with them. In July 1918 the decision was made to kill them all. Taken down into a cellar, they were summarily shot along with their doctor, their servants and one of their pet dogs.

A short, slight man, Nicholas had succeeded his huge bear of a father, Alexander III, in 1894. Nicholas had inherited a pale complexion from his Danish mother Maria Fëdorovna (née Dagmar) and lost his summer ruddiness as autumn drew on. He engaged in few recreations except hunting in the winter and shooting pheasants in the autumn, but felt it right to drop these pursuits in wartime.

There was an ascetic aspect in Nicholas’s character, and even on winter nights he left the window open. He loved the fresh air in any season and spent at least two hours in daily exercise out of doors – four if he had the chance. He thought nothing of striding from his palaces without an overcoat on the coldest December day. The emperor, mild of manner, was tough as old boots. He was indifferent to luxury. When in civilian dress, he wore the same suit he had used since his bachelor days. His trousers were on the scruffy side and his boots were dilapidated. For food, he favoured simple Russian dishes like beetroot soup, cabbage soup or porridge – European-style refined cuisine was not to his liking. He was no drinker, and when champagne was put before him at banquets he just took a few sips as a token of conviviality; he handed bottles from the Alexander Palace wine cellar to his guard commander with the comment: ‘You know, I don’t drink it.’ One witness claimed that at dinner with the family, he usually took a glass of aged slivovitz followed by one of madeira. Although others mentioned different beverages, all agreed that he was unusually restrained in the amount that he quaffed.

Tradition was important for him. Among his ancestors, he disapproved of Peter the Great as having broken the natural course of Russian historical development. He disliked Russia’s capital, St Petersburg, because he believed it out of joint with the customs of old Muscovy. To Nicholas’s way of thinking, the city had been founded on ‘dreams alone’. The Russian heritage from the centuries before the reign of Tsar Peter appealed to him. With this in mind, he frequently wore a long red shirt. He ordered his entourage to refrain from using words of foreign origin and scored them out of reports that came to him from ministers and generals. He even considered a project to change official court dress to something more like what people had worn in the reign of Emperor Alexei, the founder of the Romanov dynasty in the early seventeenth century. He thought of himself as a quintessential Russian. He adored the music of Tchaikovsky. After a concert in Livadia by the singer Nadezhda Plevitskaya, he effused: ‘I always had the thought that nobody could be more Russian than I. Your singing has shown me to be wrong. I’m grateful to you from the bottom of my heart for this feeling.’

Though Nicholas was a devout Christian, he abhorred long church services and having to get down on his knees. His faith was grounded in ideas that even some in his entourage regarded as being no better than superstitions – his favour for the self-styled ‘holy man’ Grigori Rasputin, whose drunken binges and serial promiscuity became a public scandal, was taken as proof of his eccentricity. Nikolai Bazili, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs official at the high command HQ, was to recount: ‘He was born on the saint’s day of Job and believed that fate condemned him for this. He thought that he had to pay for his ancestors whose task had been so much easier.’

Categories International Non-fiction

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Pan Macmillan SA Robert Service The Last of the Tsars