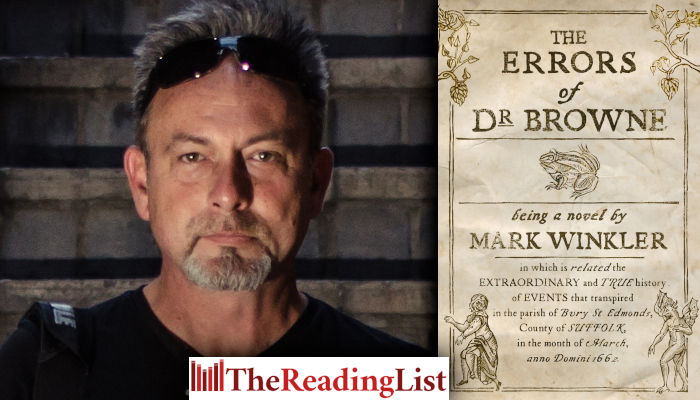

Five Minutes with Mark Winkler on his new novel The Errors of Dr Browne

More about the book!

Mark Winkler on why – and how – he came to try his hand at historical fiction with his new novel, The Errors of Dr Browne.

Where did the idea for The Errors of Dr Browne come from?

I was researching something completely different when I came across the only surviving transcript of a witch trial held in England back in 1662. It was a superficial and amateurish document, but there was something intriguing about it. Thomas Browne was mentioned, almost in passing, as a witness, and I thought that narrating the story from his point of view might be an interesting challenge.

Dr Browne thinks of himself as a good person, only to realise, too late, that he has made a terrible mistake. Do you think it is possible to move past regret?

Perhaps the psychology of regret isn’t that different to the psychology of bereavement. Regret also involves loss, sadness, hurt, and the impossibility of turning back the clock to alter the events, actions and decisions that led up to it.

Tell us about the research you had to do. Were you able to travel? And the most astounding thing you learnt?

If I were to print out the research I did for Errors, it would make a pile many times taller than the manuscript itself. I discovered soon enough that research was critical on every level, from the banal to the substantial. Social research on fashions, food (what did one wear, or have for breakfast, in 1662?), religious beliefs and behaviours. All came to bear on the novel, if not materially then texturally. But the bulk of my research centred on Browne, who features in innumerable biographies and academic documents. I read (most of) his Pseudodoxia Epidemica and Religio Medici, plus a smattering of his other writing, and in this my most valuable discoveries lay between the lines, where the personality of this remarkable man shone through beyond the text itself. This was invaluable in helping me settle on a literary voice and character for the doctor – a process not unlike trying to tune a guitar to a piano by ear.

I completed the first draft (of eight or nine) just before lockdown in 2020, which kindly put an end to any ambitions I’d had to visit the land of Browne. Turning to the Internet, I ended up strangely pleased about this – it was clear that Norwich, Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds were now no less a rash of chain-stores, parking garages and Starbucks than other modern cities. Like 1662 itself, much of what I’d hoped to uncover had long disappeared. But there was a purity in the old maps, artworks and literature I’d dug up online that in my rewrites helped me focus more narrowly on how these places (and people) may have been in Browne’s day. So I like to tell myself that by not travelling I was in fact able to create a far stronger sense of place than if I had.

I was amazed to discover that the so-called ‘spectral evidence’ entered into the Bury St Edmunds’ trial would set a legal precedent for the more famous witch trials held in Salem, Massachusetts, thirty years later, where it led directly to the execution of 19 people.

But what surprised me most, within everything else that I’d learnt, was finding out that of the nearly eight hundred neologisms coined by Browne, many survive in ordinary English today. We wouldn’t be using words such as computer, approximate, electricity, disruption or causation in our daily conversations if Thomas Browne hadn’t come up with them first.

Were you able to travel to the land of Browne?

Unfortunately lockdown put an end to any ambitions I might have had. Turning to the Internet, I ended up strangely pleased about this – it was clear that Norwich, Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds were now no less a rash of chain-stores, parking garages and Starbucks than other modern cities. Like 1662 itself, much of what I’d hoped to uncover had long disappeared. But there was a purity in the old maps, artworks and literature I’d dug up online that in my rewrites helped me focus more narrowly on how these places (and people) may have been in Browne’s day. So, I like to tell myself that by not travelling I was in fact able to create a far stronger sense of place than if I had.

A little bird told me that you do not like historical fiction. And yet, this book is a prime example of the best historical fiction has to offer. Why your apparent dislike in the genre?

It’s true that I’d rather read Conrad or Hardy or George Eliot if I feel like historical fare, simply because there’s a natural authenticity to the observations and experiences of an author’s own time. History is a bit of a sieve, with more holes than substance, and modern writers of historical fiction will sooner or later have to turn to their imaginations to compensate for historical lacunae in the lifestyles, language, mores and behaviours of their chosen period, no matter how much research they’ve done. I know I had to. So Moby Dick rings truer to me than, say, Ian McGuire’s excellent North Water, even though the writerly stitches holding together this patchwork of historical fact and imaginative interjection are invisible.

In writing circles you are known as a chameleon – your style changes from book to book. Why is that?

I’m not sure it’s done me any favours, but after my first book was published back in 2013, the last thing I wanted to do was write another one just like it. Over a lifetime of reading I’ve developed a fascination with the indivisibility of voice and character, and in all my subsequent books the storylines has emerged from the core of character and voice. Mostly, though, it’s a personal challenge: how can I tell this story in a unique way, and can I credibly sustain this voice (and grow this character) over 80,000 words? Errors is my sixth novel, and for each of them five or six attempts were abandoned when my early experiments couldn’t answer these questions positively.

For many years, you had a fulltime job and wrote at night and in-between. Now you are in the lucky position to be a fulltime author. Tell us about the changes you’ve made?

Ironically, the structure of my day-job gave a clear structure to my writing time. I would know exactly where and when I’d be able to sit down and write, and the knowledge that I’d be heading back to the office on Monday morning was enough to make sure that I did, in fact, write. So, far from being a full-time author these days, my time is carved up by freelance work, running the family business with my sister, fighting with a manuscript called This Mess You Left, and trying to elevate myself above my current rank as the world’s second-worst guitarist.

The Errors of Doctor Browne is out now.

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

About the book

Beguiled into accepting the dual roles of inquisitor and witness in one of England’s last witch trials, Doctor Thomas Browne embarks on what his biographer, Edmund Gosse, later calls ‘the most culpable and stupid action of his life’.

In Bury St Edmonds, 1662, two widows are charged with acts of witchcraft. Doctor Browne is known as a philosopher, natural scientist, logician and medical doctor, yet despite his best efforts, the trial hinges on the admissibility of ‘spectral evidence’: the accused women are deemed to have the ability to exploit their victims through dreams, which will set a legal precedent for the infamous Salem, Massachusetts witch trials thirty years later.

Conflicted by his deeply held religious beliefs and his confidence in the validity of emerging scientific methods, Browne is left to ponder the true nature of culpability – and whether the most insidious evil is, in fact, that which we carry within.

Mark Winkler’s historical novel is a wry and insightful glimpse into the limits of reason, the fear of women and the patriarchal need to control every aspect of womanhood, and our ongoing preoccupation with reputation.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Interviews Mark Winkler Penguin Random House SA The Errors of Doctor Browne The Penguin Post