Paula Hawkins on how curiosity and her early life in Zimbabwe inform her bestselling novels

More about the book!

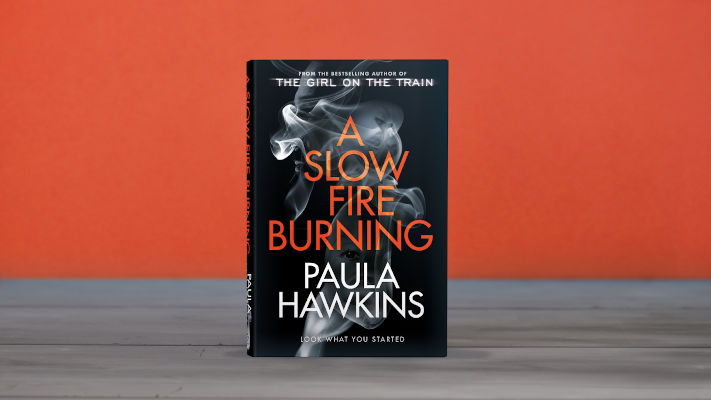

Paula Hawkins is the bestselling author of The Girl on the Train, and her latest novel, A Slow Fire Burning, is yet another unputdownable thriller. She chats to Lauren Mc Diarmid about curiosity, writing women’s stories and the psychology behind people who do terrible things.

‘I am concerned with how people arrive at a place at which they are prepared to do terrible or extreme things.’

I’ve always been a curious person, and possessed of a very overactive imagination. I think the observant side of me developed later. I moved from Zimbabwe to England when I was seventeen, and felt very much an outsider then; the move was a bit of a culture shock and I struggled initially to make friends. I think that period of sitting on the sidelines, looking at others going about their lives, made me watchful. And then later I became a journalist, so you need to watch and listen carefully when that is your job.

Curiosity is essential, too, for someone who wants to create vivid characters. You have to look at people in the street or at the next table in the restaurant and wonder, who are they? What is the relationship of that very young girl to the older man who is sitting at her side?

Women’s stories are central to A Slow Fire Burning, just as they were in my novels, The Girl on the Train and Into the Water. The easy answer to why I write about women is because I am one. I am particularly interested in the lives of women who feel like outsiders, or who are seen as outsiders, who might be found wanting by society’s exacting standards for what the right sort of woman should be. Because, despite all the progress women have made over the past half century or so, there remain certain societal expectations about women: to be pretty and pleasing, compliant and nurturing, to marry and have children. What happens to women who refuse those things? Or women who try to do what is asked of them and fail?

Laura from A Slow Fire Burning emerged from a story I had been told by a friend about someone she knew who had been in an accident: this young woman’s personality was altered after the accident, and I found myself wondering, what might that be like? What would that mean for her, for the way she was seen by others, treated by others, for how she lived her life? The origins of Carla’s character are murkier to me now, but they centred on her loss; on what a tragedy like losing a young child would do to a person, to a marriage, to a family.

This is how my characters usually develop: they come from a snippet of a story – that someone has told me, or that I have read in a newspaper – but that only forms the skeleton. I have to put the flesh on the bones.

I think you have to love all of your characters – even the less likable ones – to some degree in order to be able to develop them fully. I felt quite hurt when people talked about Rachel from The Girl on the Train as an awful person! She was never awful to me: she might have done awful things, but I felt quite tender towards her. And I do towards the characters in this book, too – especially Irene and Laura, both of whom are so spirited and determined.

When I dive into a new novel, I have an idea of the direction I want it to take, but I do not have a clear map. I need to have a few certainties: who is responsible for the crime and why, for example, but beyond that, I try not to plot in too much detail. I find that writing a very detailed plot outline robs me of one of the joys of writing a novel, which is the joy of discovery, the unearthing of new ideas and connections which you make when you are deep into a book.

Acts of violence in and off themselves are not interesting to me, rather I am concerned with how people arrive at a place at which they are prepared to do terrible or extreme things. I’m also fascinated by the impact of trauma or tragedy on the mind, on the ways we behave in the wake of a terrible event, both immediately and years down the line. I am interested in how people deal with their pain.

Once they put down the book, I want readers of A Slow Fire Burning to feel satisfied at the resolution of a mystery, but I want them to wonder, too. I want them to be left with questions: was what happened just? Did the characters get what they deserved? I would like to write the sort of books that readers want to re-read, to go back to see what they might have missed the first time around.

A Slow Fire Burning is out now.

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

Categories Fiction International

Tags A Slow Fire Burning Paula Hawkins Penguin Random House SA The Penguin Post