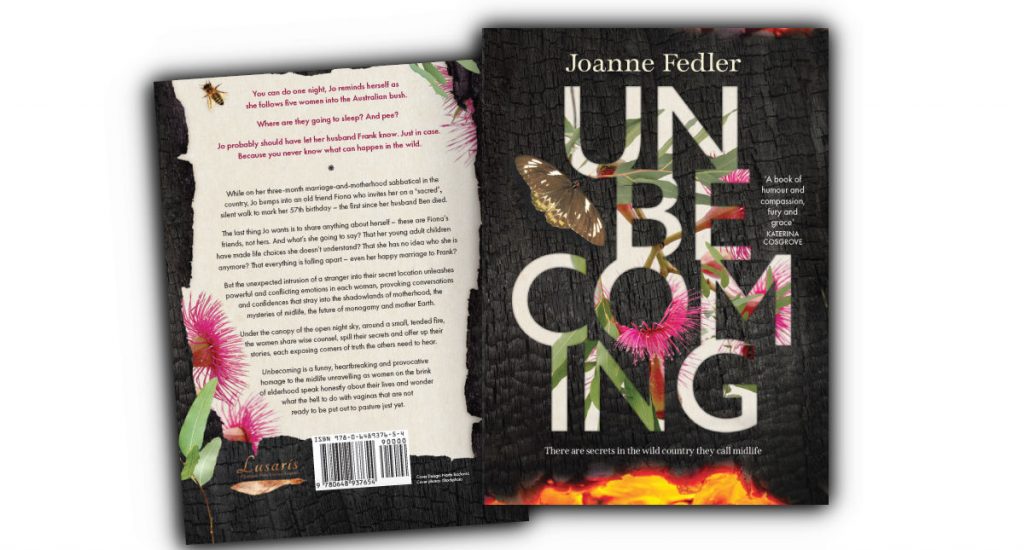

There are secrets in the wild country they call midlife – Read an extract from Unbecoming by Joanne Fedler

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from Unbecoming by Joanne Fedler.

About the book

You can do one night, Jo reminds herself as she follows five women into the Australian bush.

Where are they going to sleep? And pee?

Jo probably should have let her husband Frank know. Just in case. Because you never know what can happen in the wild.

***

While on her three-month marriage-and-motherhood sabbatical in the country, Jo bumps into an old friend, Fiona, who invites her on a ‘sacred’, silent walk to mark her 57th birthday – the first since her husband Ben died.

The last thing Jo wants is to share anything about herself – these are Fiona’s friends, not hers. And what’s she going to say? That her young adult children have made life choices she doesn’t understand? That she has no idea who she is any more? That everything is falling apart – even her happy marriage to Frank?

But the unexpected intrusion of a stranger into their secret location unleashes powerful and conflicting emotions in each woman, provoking conversations and confidences that stray into the shadowlands of motherhood, the mysteries of midlife, the future of monogamy and Mother Earth.

Under the canopy of the open night sky, around a small, tended fire, the women share wise counsel, spill their secrets and offer up their stories, each exposing corners of truth the others need to hear.

Unbecoming is a funny, heartbreaking and provocative homage to the midlife unravelling as women on the brink of elderhood speak honestly about their lives and wonder what the hell to do with vaginas that are not ready to be put out to pasture just yet.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

CHAPTER 14

The Point of Kids

Liz thinks. ‘I’m sorry I hurt them. It would probably have been better for everyone if I’d never had kids.’

I’ve never heard such a candid expression of remorse, the kind whispered at confession, if at all. Procreation is exclusively a liturgical discourse of the ‘miraculous’ and the ‘blessed’ – a child is the ‘treasure’ salvaged at the end of a shipwrecked marriage or the postpartum ‘gift’ of a disfiguring birth or even one in which the mother dies. Having kids is a life choice, like any other. We don’t crucify people who regret their marriages, career choices and other life-altering decisions. Why is motherhood a protected species?

‘But then you were happy when you left, yes?’ Yasmin asks. She is working relentlessly to discover Liz’s happiness, a devotee.

‘When I wasn’t feeling guilty.’

‘Sounds like you were screwed either way, luv,’ Cate says. ‘I don’t know why we think it’s unnatural for a mother to leave her kids. It happens in Nature all the time.’

Liz rubs her feet. ‘I can’t imagine they’ve developed the antidepressants I would’ve needed if I’d devoted my life to raising a family. Someday you just have to look in the mirror and face the truth about yourself. I love my kids. But I chose myself over them.’

I, by contrast, kept choosing my kids. Right here, I’m thinking, might be where I failed. Of my many errors of affection, the one that has returned to cut me most deeply is that I over-wanted a

family. While most kids hunger for more time and attention from their parents, mine probably would have preferred less. I don’t know how to love anyone casually, or just enough. Everything I do is over the top. I hadn’t considered how that might make a child feel. I spun my love into a technicoloured dream coat, too weighty for everyday wear. As much as a child needs to know they were wanted, perhaps it’s exhausting to be that wanted.

This parenting gig screws you, whether you take the left or the right turn. Pursue your own dreams, and you’ve abandoned them. Stay and you’re overbearing. Liz left, and Chloe doesn’t speak to her. I stayed and Jamie hardly talks to me. It’s inevitable – we will burn the rice whether we watch it or walk away. It’s perplexing, really, why I don’t feel more liberated. This here is a new conversation, the kind I have longed to have.

Among these strangers, it feels safe enough to wonder aloud why we assume living in packs is what humans were made for. Or why we pretend one size fits all when anyone who has ever wept in a dressing room knows this is gaslighting of the most pernicious kind. It seems natural to outgrow a nest and to keep moving when we’ve exhausted the land, like indigenous people do to give it a chance to regenerate. Maybe families should have expiry dates, like medication and processed food, so we know, ‘This is good for a while, but be warned, it may go funky.’

For years, I’ve showered with other peoples’ underwear, swimmers and cycling shorts hanging over the tap. I’ve sighed silently over milk left on the counter to spoil. I’ve cursed at peaches in the vegetable crisper bruised by beers plonked on top because ‘there was no other place in the fridge’. I’ve lived with dumbbells under the coffee table, a toolbox in the dining room just as Frank has put up with piles of books next to my bed, and the clutter of cosmetics by the sink. I ate beef sausages and spaghetti bolognaise once a week for fifteen years when they were all Aaron would eat. I said, ‘Sure, why not?’, when everyone wanted the 77-inch flat-screen tv and sat through Mission Impossible 13 because that’s what everyone else wanted to see instead of A Star is Born. Frank still wakes me every single night when he comes to bed after midnight, pilfering my rem sleep as if it were sidewalk furniture for the taking.

My efforts with Frank have been valiant, if not flawed and disappointing in ways neither of us could have predicted. A family is the Milwaukee brace on our free spirits. But it’s fair because everyone is compromising, shaving themselves down so that the alignments don’t cause nerve pain in others. I’d always regarded my pliability as a strength, not a weakness. Adults compromise. Grown-ups cooperate. Only toddlers and teenagers can’t or won’t share. The middle ground, devoid of non-negotiables, is a sturdy foundation on which to build a family. I’ve bent willingly, lovingly, to make room for what makes Frank and the kids come alive.

But these small refrains from asking myself, Is this okay?, have accumulated like a build-up of cholesterol in the arteries. My identity has begun to sag. And now, in my midlife, the self against whom these questions might have been measured – the person who at one time might have said, ‘Hell no, I fucking hate curtains. I adore French shutters,’ and ‘I’d rather have a piece of Aboriginal art as the centrepiece in our living space than an enormous flickering screen’ – that person is no more. I reached in one day, and my hand moved straight through her, as if she were a ghost. The neural pathway of ‘I want’ has died and all I know now is ‘I’ll have what they’re having’.

And this is why I’m sitting in this circle in a cave, in a cove god knows where, instead of in front of the tv while Frank guesses the right answers to Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

~~~

Categories Fiction International

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Joanne Fedler Penguin Random House SA Unbecoming