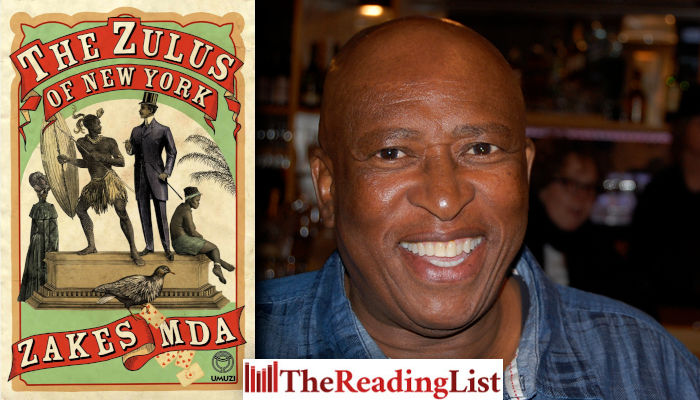

‘The Wild Zulu. That’s what the banner says.’ – Read an excerpt from Zakes Mda’s new novel The Zulus of New York

More about the book!

The Great Farini would stride on to the stage and announce, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, and now for the highlight of the day, the ferocious Zulus.’

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from The Zulus of New York, the new novel from Zakes Mda.

About the book

The impresario Farini introduced Em-Pee and his troupe to his kind of show business, and now they must earn their bread. In 1885 in a bustling New York City, they are the performers who know the true Zulu dances, while all around them fraudsters perform silly jigs.

Reports on the Anglo-Zulu War portrayed King Cetshwayo as infamous, and audiences in London and New York flock to see his kin. What the gawking spectators don’t know is that Em-Pee once carried nothing but his spear and shield, when he had to flee his king.

But amid the city’s squalid vaudeville acts appears a vision that leaves Em-Pee breathless: in a cage in Madison Square Park is Acol, a Dinka princess on display. For Em-Pee, it is love at first sight, though Acol is not free to love anyone back.

Read an extract from The Zulus of New York:

~~~

1.

New York City – November 1885

The Wild Zulu

The Wild Zulu. That’s what the banner says. Crowds line up at Longacre Square to pay their admission fee into an arena encompassed by bales of hay. Some are already sitting on the bales that are randomly placed on the ground, while others are massing in front of an iron cage.

The Wild Zulu sits in the cage and is resplendent in faux tiger skins and ostrich feathers. He is a giant of a man, bigger than any man Em-Pee has seen. He roars and the spectators gasp in anticipation. A Mulatto urchin outside the cage accompanies the rumble with a conga drum and a tambourine.

The spectators are a motley assemblage of dandies who must have strayed from the saloons, peep shows and gambling dens of the nearby Tenderloin, and workmen in overalls on a lunch break from the carriage factories, tanneries, saddleries, harness shops and horse dealerships that pervade the vicinity. Some of the gentlemen, probably out-of-towners, are accompanied by ladies in their finery.

The drummer boy performs a grotesque jig as he beats the conga. He is, however, subdued so as not to steal attention from the main attraction in the cage.

The Wild Zulu’s pecs ripple and his bloodshot eyes protrude and roll out of sync. The impresario, a pudgy White man in friendly muttonchops and a shiny stovepipe hat, struts in front of the cage. He is no longer the genial Davis that Em-Pee and Slaw met a week ago when he arranged for Em-Pee to come check out the show. He is all business and does not even cast a glance in Em-Pee’s direction. He cracks a whip; The Wild Zulu roars even louder. The dudes cheer and their ladies quiver, holding tightly on their beaux’s arms. The workmen, clustering mostly at the rear of the makeshift arena in deference to the upper-crust folks, heckle as they chomp from their lunch boxes, ‘Come on, let’s see some action! We ain’t got all day!’

‘Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, dudes, dudines and dudesses, now for the most exciting part,’ says the impresario, playing to the ladies. He turns to those who are so close to the cage they are almost touching the bars. ‘Be careful,’ he warns them ominously. ‘Stay clear of the cage lest The Wild Zulu reach for your limb between the bars and tear it to pieces with his teeth. He’s very hungry, and like all the race of his tribe he is partial to human flesh. He hasn’t had a morsel for two days.’

A kindly lady throws a banana into the cage. The Wild Zulu roars and kicks it out.

‘What a waste of luxury fruit,’ exclaims a man, reaching for the banana.

Davis, on the other hand, is livid.

‘Don’t feed The Wild Zulu!’ he yells. ‘What makes you think he eats bananas like a monkey? The Wild Zulu ain’t no monkey. He’s deadly. He’s not called The Wild Zulu for nothing. In their natural habitat baby Zulus suckle from she-wolves. They wrestle with grizzly bears as a rite of passage when they are teenagers. Stand back, stand back! You don’t want to provoke The Wild Zulu or he’ll eat you for breakfast.’

The crowd is on edge as it gives way for a Black man in dungarees pushing a wooden wheelbarrow laden with raw meat and a live cockerel, its legs tied together with twine. The bird flaps its wings frantically as the Black man transfers the wheelbarrow and its contents to Davis. The impresario carefully unlocks the cage, throws in the chicken and the meat and shuts the door quickly before The Wild Zulu can pounce on him. The spectators scream and shriek as The Wild Zulu dives for the chicken. He rips it to pieces with his bare hands and teeth and begins to eat it alive. Blood splashes all over the cage as he chews voraciously on its innards. He reaches for a chunk of meat and takes a bite from it and then from the chicken, chewing it with feathers and all. The spectators are frenzied, as if thrilling currents are jolting their way through their bodies.

Em-Pee can no longer stomach it. He walks away. But only a few steps behind the cage. His mouth fills with saliva and he spits it out in a jet.

He lingers for some time near the baled-hay barrier but does not exit, fearing that the entrance-keepers may not let him in again. Davis will not be there to explain to them that he is his special guest. Some bouncers are busy shooing away the opportunists who are trying to view the performance from outside over the barrier.

He stands on a bale and watches a barker walking up and down the sidewalk reciting superlatives about the ferociousness and savage prowess of The Wild Zulu and inviting passers-by to come and see the spectacle for themselves. The barker strays into the street, still touting the merits of the show among stagecoaches and hansoms whose drivers are yelling and shaking their fists at what has developed into a traffic jam. For Em-Pee they are more entertaining than The Wild Zulu. He watches for a while and wonders if Slaw will make it on time.

His stomach has calmed down. He must force himself to watch the whole performance. He has no choice. Slaw will demand a full report. Every detail from the beginning to the end. So he drags his feet back. People give way until he is at his original spot in front of the cage. Curious eyes follow him. Perhaps they think he’s connected to the show somehow; maybe he’s a labourer in the employ of the impresario. He is the only Black man in this audience of New York’s gentry and sundry aspirants to status.

Once such spectacles were the preserve of the lower rungs of society while the crème de la crème took refuge in the private boxes of the Academy of Music Opera House and, most recently, the Metropolitan Opera House – opened only a month ago by old money that feels squeezed out of the Academy by the nouveaux riches. But these days not only do these circuses attract the vulgus and the pretenders to wealth and class, but some of the important names of the city have been spotted enjoying the gore, especially when they are staged at such venues as Madison Square Garden. Even the denizens of Broadway theatre establishments can be sighted occasionally indulging in them. All thanks to the most supreme impresario of all time, the one and only, The Great Farini, who has popularised such shows and has turned them into respectable entertainment. Many a member of the New York intelligentsia becomes a regular at these spectacles of primitive races under the pretext of being an exponent of popular anthropology or an aficionado of Charles Darwin’s postulations.

2.

KwaZulu – December 1878

Ozithulele The Silent One

His Zulu colleagues call him Mpi, which has become Em-Pee to the English-speakers. It is less punishing to the inexperienced tongue than Mpiyezintombi – Battle of the Maidens – so named because his father thought he was so handsome that women were going to fight over him.

When they are drinking beer all by themselves, without the White troupe members, the Zulus recite their clan praises. He takes pride in his name, Mpiyezintombi Mkhize, begotten by Khabazela kaMavovo, descendant of Sibiside, he who led the abaMbo people from the blue lakes of central Africa, many centuries ago, to the area that later became known as kwaZulu, where they were incorporated into the amaZulu nation through King Shaka’s spear in the nineteenth century.

When he recites his praises, his colleagues ululate like women and it takes Mpi back to the old country where he used to carouse with the young women of King Cetshwayo kaMpande’s isigodlo – the very behaviour that brought about his downfall and his flight from the kingdom.

His escape had been unpremeditated. He carried nothing but his spear and shield when he set off from Ondini in the deep of the night. Occasionally he listened on the ground to the sounds of the night, hoping that none of them would be from the heavy gait of amabutho, his warrior colleagues, sent by King Cetshwayo to capture him.

When the December sun rose and scorched his back, he took circuitous routes through the bushes. But soon he would be out in the open veld and the humid heat would do its business on his skin. Occasionally he stood on a hillock and looked back. There was no sign of anyone chasing him and he was relieved. But he would not feel safe until he reached uKhahlamba Mountains and crossed rivers into the land of King Letsie, where he would seek asylum.

Letsie’s father, Moshoeshoe, had established a reputation for wisdom and generosity. From the exiles of many nations, he had formed his formidable Basotho nation. Perhaps his son had inherited similar traits and would give succour to Mpiyezintombi, son of Mkhize, who was running away from the wrath of Ozithulele, the Silent One, as Cetshwayo was called.

Mpiyezintombi cursed his foolish lust as if it was something out there acting independently of him. It was fine when he was just playing the fool with the young women of the King’s isigodlo, clowning about, making them laugh with his antics and gourmandising the delicacies left over from the King’s bowls that the young women furtively placed at his door. The mistake happened when he fell in love with one of them – the plump, yellow-coloured Nomalanga. It was an illicit desire, for she belonged to the isigodlo – the royal household comprising the residences of the King’s wives and children, and also the private enclosures of the girls presented to him by various vassals as tribute, or selected by him from distinguished families among his subjects to serve him, purportedly as his adopted daughters. Nomalanga was one such girl.

As he traversed hills and crossed rivers, Mpiyezintombi regretted that he had not stolen one of John Dunn’s horses. His flight would have been more comfortable, and he would be far by now. Jantoni, as his fellow amaZulu called John Dunn, wouldn’t have missed one measly horse when he boasted a harras of thoroughbreds. Even if he eventually discovered the theft, Mpiyezintombi would be in other kings’ jurisdiction by then.

His biggest regret was that of betraying the trust of the Silent One in the first place. It was trust that had been earned over many years, from as early as the days he sat on his father’s knee as a toddler listening to stories of his heroic service to the kingdom. Although at first it was only the songs accompanying the stories that interested him, at the age of about three they began to mean something and became part of him.

His father was a member of iHlaba Regiment under King Dingane kaSenzangakhona. He took pride in the one act that brought universal fame to that regiment – the assassination of the Trek-Boer leader Piet Retief and his men. He narrated with delight how Dingane had initially given Piet Retief tracts of land and how his councillors had objected. Most vocal was the induna of the Ntuli Clan, Ndlela kaSompisi. He was the man who took the decision that Retief should be killed.

Retief and his men were invited to join the King in a corralled assembly yard. They were instructed to leave their weapons outside. When the discussion was proceeding, the infantrymen of iHlaba Regiment entered singing a war song. Mpiyezintombi always remembered how his father used to sing a few bars of the chorus as he narrated the story: ‘Muntu wami kwaZulu / Wangena! / Wakhuza iwawa / Wangena!’ ‘My person of kwaZulu / He entered! / He yelled out a war cry / And he entered!’

His father’s voice would quiver with excitement at this point.

At the sound of the war cry iwa-w-a-a-a, the men of iHlaba Regiment fell upon the Trek-Boers and beat them to death with sticks and knobkerries. Their Black servants suffered the same fate. All the bodies were dumped in a donga whose banks were then collapsed, burying the dead in a mass grave.

As the son of a man from such a distinguished regiment, Mpiyezintombi was therefore held in high esteem by King Mpande, who succeeded King Dingane, and by Prince Cetshwayo, whose praise poetry included the lines ‘Nango ke ozithulele ji, akaqali muntu’, ‘Here is the silent one, he does not provoke anyone.’

Indeed, the Prince was known as a man who never started conflict. But if anyone dared to provoke him, his response was swift and final. People did not forget how ruthlessly he dealt with his brother-princes when they were bludgeoning one another in some battle of succession.

Six years before his escape from his comrades-in-arms, Mpiyezintombi was a member of the regiment of one thousand and five hundred soldiers who accompanied Prince Cetshwayo, soon after King Mponde’s death, on a long march from his homestead in the western region to the capital to claim the throne. The regiment was ready for battle in case any of the other princes got some twisted idea that he was a more rightful heir than Cetshwayo.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Penguin Random House SA The Zulus of New York Umuzi Zakes Mda