The Kruger National Park – a game reserve that very nearly wasn’t – read an excerpt from David Bristow’s new book Of Hominins, Hunter-Gatherers and Heroes

More about the book!

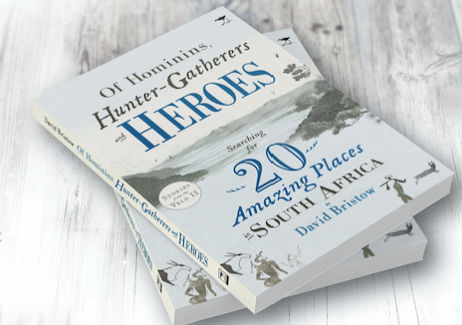

Of Hominins, Hunter-Gatherers and Heroes: Searching for 20 Amazing Places in South Africa by David Bristow offers spellbinding stories of some amazing, little-known places in South Africa.

Bristow ventured to some lesser-known or visited places – but they each get a new treatment.

Of Hominins, Hunter-Gatherers and Heroes is a journey through a bucket list of must-see places in this ‘world in one country’.

These stories will excite, entertain and enthral you.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Kruger National Park

Big Game, Big Trees and a Ticking Conservation Time Bomb: Searching for a Game Reserve that Very Nearly Wasn’t

The Kruger Park needs no introduction. What is does require, however, is to highlight how precarious were its early years, how tentative the creation of our first national park and the uncertain future it now faces.

Could you conceive of a South Africa – or a book about its most remarkable places – without a Kruger National Park? The very thought is unsettling. Kruger is not only this country’s flagship national park but also one of Africa’s top five game reserves, no contest.

The park’s north-south distance is matched only by that of Namibia’s Namib-Naukluft National Park. But that strip of desert has just two main habitats and precious few large animals; the Kruger has a rude abundance of both. The considerable diversity of landscape and vegetation of the South African Lowveld, which is covered almost entirely by the park, is the result of numerous interacting elements.

To begin are the elevational and latitudinal differences between the relatively high, cool and fertile country around Pretoriuskop in the southwest, to the low, arid, fever-ridden river valleys around Crook’s Corner in the extreme northeast. Then there are the soils, and there are few other places, not just in South but all of Africa, with such a varied mixture.

Working backwards on the geological timeline, they begin with the gravelly alluvial soils of the main river valleys, predominantly the Limpopo and its tributaries. Also of relatively recent vintage are the sodic (salty) soils, which cover much of the ground between Punda Maria and Letaba rest camps.

This is the mopane belt that on the surface appears bereft of animals, but in reality is quite the opposite. Most of the reserve’s elephants and buffaloes are to be found here, it’s just not always easy to see them in among the dense cover.

Stormberg volcanics (Late Karoo period, circa 100 mya) comprise the Lebombo hills all along the park’s eastern boundary. These are preceded in time by Early to Middle Karoo sandstones and shales (about 150–250 mya, wherein all that controversial coal is to be found). Most of the park’s southern half comprises ancient granite that is about half the age of our planet, two billion years give or take a few hundred million.

Finally, there are the greenstones which, although thinly distributed, are the stars of the geological story. They form the Barberton Mountain Land suite of rocks, our newest World Heritage Site. It’s not everywhere you can see and touch antediluvian rocks dating back about three-and-a-half billion years, to the time when the first proto-continents were forming.

Not just that, but what are believed to be the oldest known forms of life have been found in these rocks. You’ve come a long way, and it’s been a rough trip, Homo sapiens. Congratulations for making it this far after a shaky start as bacteria and algae.

All this translates into trees. It is the trees, the big ones, that set the Kruger Park apart from any other game reserve in the country. Indeed, there are very few other reserves on our subcontinent that have anything like the variety and scale of trees to be found here – an astonishing 336 species.

To begin an alphabetical liturgy, first come the more than a dozen acacia species (or whatever the botanical knobthorns now want us to call them); following them are the baobab, that titanic succulent of the driest, hottest areas; then buffalo thorn; about a dozen species of bushwillow; boerboon; coral tree; greenthorn; guarri; jackalberry; karee; kiaat; marula; mopane; monkey orange; mountain syringa; nyalaberry; purple-pod terminalia; rain tree; silver tree; sour plum; tamboti; wild figs (several species) and wild pear.

That’s around 46 species, 290 to go … On the surface, the Okavango Delta and surrounding arid Kalahari savanna does look like a leafy challenger, but in truth is not that well endowed with different species. The Lowveld is the place of big trees and, even without consciously making the connection, trees mean birds and again only the Okavango rivals the Kruger for avian abundance.

Obviously, we go there primarily to see animals large and small, but beneath that is a sense of venturing back in time into a fantastical Pleistocene park where things remain as they were at a time before we humans came along and changed (one is tempted to use the word ‘ruined’, but these things are relative) it all.

This is the Africa we think of when we say we feel we belong there in some visceral way, like we are going back to our primordial home. That we have ingested the red dust of Africa into our bloodstreams and have become intoxicated on the heady infusion.

Not to be outdone by Hollywood’s Jurassic fantasyland, the Lowveld of today has its own creatures fantastical and unlikely: lumbering pachyderms, some with unicorn-like horns, others with great tusked teeth and hose-pipe noses; herbivores with necks so long you’d expect them to snap in a strong wind; fearsome toothed and clawed predators that seem to leap out of our nightmares. Sometimes you need to remind yourself just how unlikely it all is.

And then there are the Kruger’s rest camps, like no other in this region or any other. The names alone are a poem of Africa from a bygone age: Skukuza and Letaba, Lower Sabie and Satara, Shingwedzi and Punda Maria. Each site was chosen for its natural beauty and tree cover. Some people, mostly long-time visitors, prefer to sit at camp during the middle of the day to just watch the birds and other small critters of these arboreal ecosystems.

At night the rest camps are redolent with the intoxicating aromas of acacia-wood fires and sizzling boerewors. Most of the camps were named for the rivers along whose banks they spread. One exception is Skukuza which reclines under substantial tree cover at the confluence of the Sabie and Sand rivers.

Punda Maria is another, and it was named by the first ranger of the far north, JJ Coetser. He had served in East Africa during the First World War where he’d picked up some Swahili. Clearly, he misheard the local name for zebras and thought that the striped donkeys (punda miliya) had an amusing similarity with his wife, Maria’s, name (and punda being slang for woman).

Early days in the park must have been either heaven or penury for the rangers and their families. There were no proper roads. Most lived in mud huts with no modern conveniences, not even running water. They had to contend with heat, drought, floods, flies, tsetse flies, mosquitoes and attendant malaria, not to mention marauding elephants, sneaking cats and all other things that slither and slide, sting and bite.

From accounts handed down, they do appear to have been a happy and tough band of ranger brothers and their wives, though. In his autobiography, founding warden James Stevenson-Hamilton called the park a Lowveld Cinderella that became a princess, so clearly he liked the place a lot.

When it came time to build rest camps, the warden believed in keeping things Spartan. The first was Pretoriuskop in 1930. He did not want visitors there lolling indoors while all of Africa roared and sang its jungle symphony all around, so he ordered the rondavels to be made cramped, with sparse facilities and pokey windows. Even cooking was to be done outdoors.

The headlong rush to modern conveniences and comfort had been propelled largely by the advent of the automobile. The first visitors had to camp, stretching tarpaulins from their cars to a tree, surround their camp with a thorn screen and were obliged to carry at least one firearm per car. Just three cars entered the park in 1927, the year it was opened to visitors.

How things have changed! For those people who like their game experience served up a bit rarer than what you find in the modern, revamped rest camps, there is Tsendze. This newest of rest camps offers only camping on a bring-all-of-your-own basis. The only head-nod to modern conveniences is solar-heated water and lights in the ablution buildings. The name means ‘to wander around in the bush as if lost’, which seems a fine way to see the wilderness.

The old timers knew not to plonk a camp in the middle of the mopane belt. But modern planners, seeing a large blank area, couldn’t resist the urge to fill it. It has a swimming pool (vital for visits during the suicide season when temperatures reach into the upper 40s), and plenty thatch, but about as much appeal as a plate of wors and pap without any gravy.

The park has some 60 marked historic sites that are worth taking the trouble to explore. For example, few people know that in the far north of Kruger is one of South Africa’s most important Iron Age archaeological sites; not even the (white) section rangers, until it was ‘discovered’ in the late 1980s. The black rangers, well versed in the world of their ancestors, had kept quiet about it.

The places that will appeal to the younger travellers are those waypoints that mark various adventures of that feisty terrier Jock, the dog made famous by the book that charmed many generations of South African children. Especially if readings round the campfire are part of the daily activities. (Another one to keep the ‘likkle ones’ amused is the Smartie game: you buy a stash and dish out various colours for each of a particular animal or bird spotted by them.)

Jock of the Bushveld was the loyal companion of Percy Fitzpatrick, one of a legion of waggoneers who carried supplies between Delagoa Bay (Maputo) and the Lydenburg gold diggings in the late 1800s. Stories about the fearless dog’s exploits were polished through many retellings in the Fitzpatrick household after the man had made his fortune and moved to a mansion on the crest of the Witwatersrand.

Among the rand lord’s friends was that champion of imperial Britain Rudyard Kipling, who gave us the Just So Stories involving the great, grey-green, greasy Limpopo. He encouraged Percy to write down his own ‘just so stories’ of his life on the road and in the bush. That is why, on the title page, you will see it is dedicated to ‘The Likkle People’.

Don’t tell the kids but here’s a spoiler alert. In the book he wrote about his famous family’s coaching company, Harry Zeederberg reckoned there never was a dog named Jock. Harry would have known Percy before he was made a ‘sir’ and reckons the young transport rider made it all up.

Most likely the story of Jock is a compilation of all the dogs and dog tales Fitzpatrick encountered during his time driving wagons. Even today, more than a century later, they ring so true that at the heart of Jock there must be a foundation based in real experience.

Not far off the Doispane Road, the old wagon route to Delagoa Bay, near Crocodile Bridge, stands historical marker number 57. You can get out of your car here to see one example of the Bushman rock art that is scattered around the park. The Stone Age hunter-gatherers, it seems, did not leave any landscape stone unturned in their peregrinations around southern Africa.

In the far northeastern corner of the park, Crook’s Corner recalls the shenanigans of the loveable, rogue elephant-hunter Bvekenya or, as would have been written on his birth certificate and numerous arrest warrants, Cecil Barnard.

The corner in question is the meeting of three countries, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. This confluence of the Limpopo and Luvuvhu rivers afforded outlaws such as Barnard an escape route from the law no matter from which direction it came for them.

Also up the Luvuvhu way is a site that should be a must on any trip to the park. It is Thulamela (or Thulamala), the Iron Age stronghold referred to earlier, that was occupied between the years 1200 and 1300 CE. This hill location, also marked by an impressive copse of baobab trees, is one of the numerous known stone settlements of people who worked iron and gold, and bartered with first Arab and later Portuguese traders.

On the Iron Age calendar, Thulamela is located between Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. Out from city states went gold, ivory, game hides and slaves. In came beads, porcelain, cloth and coins. Perhaps most interesting from an anthropological point of view is that all these ‘zimbabwe’ (stone) settlements show a clear class distinction, with an aristocracy living the life of Riley on prominent hilltops and the peasants skoffelling on the plains below.

Another significant place are the ruins of the homestead and store of the intrepid trader and hunter João Albasini, the first white man to call the area home. João was just 18 years old in 1831 when he left Lisbon to join his father at Delagoa Bay to help run a trading post there.

Delagoa Bay was the major slaving entrepôt of the day in southern Africa, a commerce that helped fuel the Difaqane wars that ravaged the region in the early to mid-1800s. At one point, King Dingane ordered an attack on the bay and Albasini was taken prisoner by the Zulu commander Soshangana. He was held captive for about six months but was eventually freed by two black traders who knew him.

When he returned to Delagoa Bay, Albasini decided to diversify the business by following the scent trail of gold and ivory into the interior. When he reached the Lowveld, he conscripted a small army of elephant hunters and became the main trader in the region of ivory and hides (lions, leopards and rhinos mainly).

Around 1846 he built a substantial home at Magashula’s Kraal, where today you’ll find its ruins just inside the Numbi Gate. This spot became a convenient warehouse for Boers from the higher ground. They would conduct speedy trading sorties in order to outrun the endemic malaria of the area, which also discouraged settlement and farming there.

Business went so well the Portuguese man built two more stores in what would become the Sabie Game Reserve. When gold fever struck the Transvaal Escarpment area, Albasini followed that trail, marrying Gertina van Rensburg of Ohrigstad in 1850.

With wealth and then the status of being appointed Vice-Consul for Portugal in the Transvaal Republic, the Alabasinis moved to the more respectable town of Louis Trichardt. In time the Albasinis married into the Zeederberg clan and today you can still find them living in the area.

All these stories sound extremely romantic and imposing, and it certainly seems like the park has been there forever. Which is not the case at all and its creation was the subject of much dispute.

In the 19th century, ideas about hunting differed between the two settler cultures. At a time when conservation ideas were seeding in the British realm, a hunter was by definition a gentleman (as opposed to a common poacher). Killing for pleasure was considered highly ethical, while shooting for sustenance or commercial gain was deemed to be savage.

The Boers upcountry had a very different relationship with nature. They considered exterminating wildlife to be not only their God-given right, but also their civic duty in order that they might clear the land for agriculture and civilization. The Transvaal (which was originally four separate Voortrekker states) had an economy based on hunting for meat, ivory and hides.

In time the more fertile agricultural areas in the south turned away from hunting and by the mid-1880s around 200 game conservancies had been established there on private farms in the Transvaal. Things in the less fertile north went differently, and ruling over them all stood the indomitable, hugely hirsute and extremely conservative president of the Transvaal or, more formally the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek, Stephanus Johannes Paulus ‘Paul’ Kruger.

The popular mythology is that Kruger was an early champion of game conservation and was the instigator behind creating reserves around the Boer republic. There are even supposed second-hand accounts published by people who knew people who remember hearing him addressing the Volksraad (parliament) extolling the virtues of and need for creating a ‘wild kraal’ in the Lowveld in order to protect the last, disappearing herds there.

Delving into the actual records paints a rather different picture. ‘Personalities such as Paul Kruger, deemed to have advanced the ‘struggle’ for nature conservation, have been elevated to the status of heroes,’ writes social historian Jane Carruthers. ‘[This has] resulted in many imaginative embellishments, and errors and inaccuracies have been repeated so frequently that they are now self-perpetuating.’

In the book The Conservationists and the Killers, author John Pringle records the son of fledgling Sabie Game Reserve ranger Major Robertson recalling a story told by his father of the time when President Kruger had tried to rally his followers with discussions about the necessity for game preservation.

The main problem with Robertson’s memory is he (the old ranger) as a junior officer in the British army, and then gold prospector, is unlikely have met Paul Kruger, let alone ever heard him speak. There certainly is no way Paul Kruger could have addressed such an audience around a fire. Kruger skipped out of town on the last midnight train bound for Delagoa Bay in January 1900, en route to exile in Clarens, Holland. The Sabie Game Reserve did not start recruiting until 1903.

What the archives actually reveal is that President Kruger was at best a hindrance to the formation of a game reserve in the Lowveld, or anywhere else, and at worst a furtive opponent. He certainly helped to stall the process.

In Kruger’s defence some people argue how he pushed for the creation of South Africa’s first game reserve on the Pongola River in 1889, the first official game reserve in South Africa. But historians point out that, firstly, it was a tiny parcel of land and, secondly, that it was part of a larger strategy on the part of the Boers. They needed a sea port and Pongolapoort was their first move in trying to secure a land passage through Swaziland to Kosi Bay.

What actually did transpire in the Volksraad in 1884 was that Kruger for the first time voiced his opinion on wildlife and what he did was oppose a motion for tighter hunting controls. The first record of any discussion in the Volksraad about a game reserve in the Lowveld is in 1888.

A commercially minded farmer from the Free State named Williams suggested such a place be established in order that it might be rented to English ‘sportsmen’ for a high price. In 1890 Williams’s idea was taken up by two other members, GJ Louw who was Justice of the Peace for Komatipoort, and Abel Erasmus, Native Commissioner for Lydenburg.

They advocated for a ‘wildkraal of reserve‘ between the Crocodile and Sabie rivers. Erasmus argued that only Africans resided in the area of the proposed reserve so the enterprise would cost only about £420 a year. Kruger and his fundamentalist supporters sat heavily on the idea.

In 1893 and then again in 1895 the subject was raised at successive Volksraad sittings, and again nothing was done. Only after some strongly worded objections did the government eventually agree to vote on the matter and the motion was passed by a majority of one.

But the Volksraad had no executive powers and so the Sabie Game Reserve did not become an immediate reality. Two more years passed and when still nothing was done by Kruger’s government, more deputations and protests followed from supporters of the ‘wildkraal’ idea, until eventually the Executive Council issued a proclamation on 26 March 1898.

But even this did not get things moving in the Slowveld. The Executive Council called for more opinions (talk about delaying tactics, you’d almost think Kruger engineered the forthcoming war to side-step the game reserve issue!). Finally, sort of, in September 1898 funds were made available for a warden to be appointed, along with four African (black) policemen.

A year later still no appointments had been made, and then all hell broke loose – the three-year hell that was the Anglo-Boer War. Naturally any talk of game reserves went up in cannon smoke. When Pretoria fell to Lord Roberts’s army in 1900, the British, no doubt driven by a healthy dose of guilt, were keen to restore civil law and order in the Boer republics.

And so begins the discussion about the first warden of the still non-existent Sabie Game Reserve. The new administration under Alfred Milner found the minutes proclaiming this Lowveld wildkraal and so advertised for a gamekeeper. In October 1900 a Lydenburg farmer and hunter, A Glynn, applied for and was given the posting. However, because Boer guerrilla units were still operating in the area he was not able to report for duty and the initiative stumbled.

A year later Boer commandos had been all but dislodged from the eastern Transvaal. This prompted the Mining Commissioner at Barberton, Tom Casement, to put up his hand. No appointment was made but a general order was issued prohibiting all military personnel from hunting there. Not all obeyed.

In June 1901, finally, Captain HF Francis, a member of the controversial Steinaecker’s Horse outfit (and this term is used about as loosely as the unit was constituted), was appointed ‘game inspector’ of the Sabie Game Reserve. But just a month later Francis was killed in action, so another ‘reliable man’ was sought.

WM Walker turned out to be that man, but again not for long. Although he had worked on gold diggings around Barberton, he turned out to be a dismal failure at the job. (One has to wonder, what with virtually no supervision and not much to do, how bad he could have been.)

By this time peace had been signed and numerous applications were received for a replacement. A Major James Stevenson-Hamilton was appointed and we can be exceedingly grateful for that. He had served with the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons and was seeking a civilian position in South Africa.

The stocky, feisty Scottish officer was 34 years old when he was appointed as the reserve’s third warden and its first on-the-ground caretaker. It was a position he would retain until retirement in 1946. Another fortuitous appointment was that of the first game ranger.

In his private notes Stevenson-Hamilton reveals much more about the failures and setbacks he encountered than the joys and successes he reveals in his autobiography. One of these is that the park tended to attract the ‘flotsam and jetsam’ of society, people who thought the job there would be one of continual shooting, drinking and lazing around.

Harry Wolhuter was another who had served in the notorious Steinaecker’s Horse, but he was no shirker. Three times in his life he was declared dead, twice during the Boer War when he contracted severe malaria, and then after his famous mauling by a very hungry male lion. Nothing seemed to be able to keep him down. Like his boss, Wolhuter remained working for the park until his own retirement.

Close to Letaba rest camp is historical site number 56, which was the northern-most outpost of the curious corps known as Steinaecker’s Horse. Colonel Ludwig Steinaecker was a flamboyant German of unknown military provenance who seemed to have washed up in the Colony of Natal some time around 1890.

When war broke out with the Boers to the north, he managed to persuade the British High Command that he be allowed to raise his own regiment. They needed all the hands and arms they could muster and so conceded: raising privately funded regiments had been commonplace in the British Army for years. The colonel apparently designed his own uniforms for the 450-strong mounted regiment.

Their only orders were: keep an eye on the enemy in the Lowveld and try to prevent any Boer artillery escaping eastwards. They did manage to blow up a vital bridge, but only after the Boers had crossed it and vanished into the bush. That in turn delayed the British forces chasing the guns by about a week.

With nothing much left to do they set up guard posts along a 300-kilometre front from Swaziland to the Letaba River. They spent their time searching for Boers to harass, fishing, hunting and drinking rum. The unit not only hunted for food and sport but even entered the trophy market, supplying other army units with curios to take back home.

At the ascension of King Edward VII in January 1901, Colonel Steinaecker presumed he would be automatically put on the guest list and so set sail for England. When he discovered he was not only not on the party list but completely unknown, he protested. This prompted the big wigs of the Home Guard to investigate. Steinaecker’s unit was found to be highly irregular; he was stripped of his rank and ordered to disband his regiment.

The fallen officer returned to Komatipoort where he resorted to wandering the streets and haranguing people with his tales of bravado and betrayal. A former subordinate living in Pilgrim’s Rest took him in. When Steinaecker attempted to kill his own horse he was arrested but, before he could be brought to trial, he committed suicide with poison he carried in the event that an honourable exit was required.

Once the Sabie reserve became a working reality, the white farmers of the Lowveld started becoming vocally hysterical that the wildlife sanctuary in their bosom was becoming a breeding ground for predators. The Transvaal Game Protection Association, forerunner of the Wildlife Society, urged the authorities to allow them access so that they might exterminate the ‘vermin’.

They need not have worried about it. For the first decade of its existence, the rangers of the reserve shot every large predator on sight – lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, wild dogs, the lot. They understood their mission was to protect the antelope, or royal game, from predators as was the case in Britain.

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, most of the rangers signed up for service. Fifty-eight-year-old Major AA Fraser, an old India hand, was left to defend the fort. He was an excellent ranger and, since his arrival at the park in 1903, had formed a close bond with the warden. However, by 1914 he had little fight left in him and was unable to hold back the advancing invasion.

Hunters, black and white, sheep grazers and cattle ranchers, mineral prospectors and other fortune seekers very quickly overran the game reserve. After armistice in 1918 it took the returning corps of rangers many years to clear the park again.

It was around that time that Stevenson-Hamilton had the revelation that a game reserve should be for preserving all game, not just antelope, in fact everything within its boundaries whether animal, mineral or vegetable: a reserve for nature’s sake. Not everyone agreed with him.

The warden spent the next decade and a half fighting off successive waves of opposition from hunters, farmers, miners and most politicians to see it finally proclaimed the country’s first national park in 1926. The battle to push the national parks legislation to its conclusion proved about as arduous as that of the original game reserve.

The so-called Pact Government, with JBM Hertzog as Prime Minister, was in power and it strongly promoted Afrikaner interests. Nature conservation was seen primarily as a British obsession and the idea had only two strong supporters in the cabinet of the day.

Stevenson-Hamilton popped into Komatipoort to do some shopping, and in the hotel there mentioned his woes to its owner. If you propose the name Kruger for your hoped-for park, no Afrikaner politician will vote against it, his hotelier friend advised.

It was this stroke of local genius that won the ayes. That hard-won event was widely celebrated, and the battle for wildlife conservation was won. However, in a chronicle of Kruger National Park it would be disingenuous not to mention the current poaching problems that have gripped it in a grim vice.

The truth is that the park has been beset with similar problems since the day it came into being. Stevenson-Hamilton’s first task was to clear the area of human occupation. When he was clearing out the black subsistence farmers and occasional hunters, he had no idea quite what harvest he might be sowing.

Black people had been living there, on and off, for a long time before white people arrived. When they were told it was now a game reserve and they had to pack up home and move out, or else, they were not amused. Skukuza, the main rest camp in the Kruger Park, was the nickname given to Stevenson-Hamilton by those same people; it means ‘to sweep clean’.

For nearly a century, middle-class and, until recently, almost exclusively white, people have enjoyed the wildlife spectacle that the park offers. But part of that experience is also a romanticised notion of how the place was before the world outside became modernised, industrialised, highly regulated and homogenised.

But for the lives of the relatively impoverished people living outside its fences and looking in, all this has little relevance, point out people like Carruthers and other critics. ‘Many people, particularly those in areas adjoining the Park, who live in extreme poverty, and who have in the past been deliberately excluded from enjoying or sharing in any of the recreational and educational benefits of the Kruger National Park, hold quite different views.’

Poaching has been endemic in the park since its inception and in fact well before. In Stevenson-Hamilton’s time it was mostly a low-key amateur affair. Today, though, it has turned highly professional and the stakes are more than one of just life and death.

Poaching and the trade in its spoils are today controlled by mainly Asian criminal cartels. They have unlimited funds and can even create markets for their goods, just as they do for the drugs they peddle around the world.

Elephant populations are being slaughtered across the continent north of here, but when those populations are depleted the guns will turn to Botswana and South Africa, where conservation appears still to be holding its own. The price of rhino horn currently exceeds the price per kilogram of any drug, which is why people are killing and dying on both sides of the poaching trenches.

And, just like with the war against drugs, you cannot hope to win the war against poaching with force. It has been tried and it has failed, or is failing, everywhere.

In communities around the park, be they in South Africa, Mozambique or Zimbabwe, poachers are regarded as Robin Hood-style heroes, bringing bags of cash and glamour into otherwise depressed areas. When a rhino poacher is arrested or shot dead the conservation community might celebrate, but the community from which they come most often galvanises around them.

The poaching war will be lost so long as local communities are not working on the side of the law and conservation, so there has to be more carrot offered to them in order to balance the current stick methods. One suggestion of late is that elephants might hold the solution.

Having been protected for more than a century, their numbers are now believed to be about double what the park can support and still maintain a healthy ecosystem. In the past the Kruger and other game reserves such as Hwange where elephant populations cause problems, culling of herds was done. But in recent decades that practice has lost general favour.

No one wants to see the Kruger’s sylvan landscape reduced to treeless wasteland as has happened across much of northern Botswana. Then again no one wants to see the elephants being ‘taken off’ in the name of conservation. And yet, it makes sense, to sacrifice some of the resources you have, and share the spoils with your neighbours, in order to turn the tide of the battle.

You wouldn’t want to be one of the people who has to make these decisions, but someone has to. It’s like when your arm has been trapped by a rock in a lonely canyon for 127 hours, and your life force is ebbing away. You have a pocketknife and the clock is ticking.

With the combined forces of land claims, poaching and radical politics gathering around the perimeter of the park, it takes a bold decision to cut off your arm in order to save yourself – or not to.

~~~

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts David Bristow Jacana Media MFBooks Joburg Of Hominins Hunter-Gatherers and Heroes