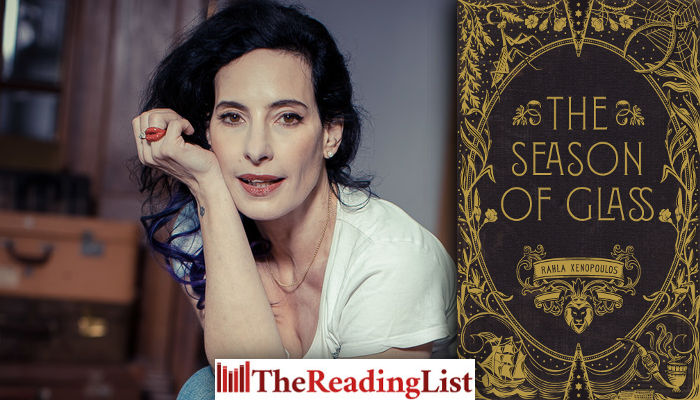

Read an excerpt from Rahla Xenopoulos’s shimmering new novel The Season of Glass

More about the book!

The Season of Glass by Rahla Xenopoulos is a modern Scheherazade’s tale about a pair of twins who travel to pivotal moments in history.

The book takes us to a marbled city in sixteenth-century India, through dangerous Johannesburg streets in the seventies, and even to the distant future.

A shimmering novel, it is a kaleidoscope that works with light and shows us hope.

Read an excerpt from the book:

The leather soles of the boy’s shoes pound the paving as he runs past Capilla del Patrocinio. Down back alleys that only sailors and whores know of, he runs, darting now left, now right down the cobbled roads, undetected by the greedy eyes of the Inquisition. He runs past priests with eyes of deception, men and women cowering terrified, street urchins starving. Past the Castillo of San Jorge where public trials will be held tomorrow. Past the wooden structures set up for hangings, and past the pyres built for the public burnings. How many heretics live in this city? Surely, with all this death, they have by now all been routed out and killed? But every day, hundreds more are killed.

He sprints through drains running with sewage and filth, blood and heartache. Putrid Seville, it is all he has ever known. His feet blister within the leather slippers he’s worn for five years, filled as they are with the mud of the city, but still he runs, no stranger to discomfort or fear. Past the abandoned swinging bodies hung this afternoon, and through the desolate marketplace, closed and empty till dawn. He runs fearless, his heart fiercely clutching the hope of another – another just like him.

Daily, and knowingly, he risks his life in the pursuit of a ducat. But this is different. He is determined to live through this night for the promise of one like him, the promise of another.

Seventeen thirty is a most dangerous time to be living in Spain, a mendacious time, filled with people pretending to be that which they are not. They say every age has its violent ways, but it would seem to me that, during these days, mankind has become resigned to the brutality of our ways. Betrayal is whispered on the breath of every man, woman, and child. Seville – just about the world entire – is run by Cardinal Benedicto Martinez. He is not so much a person as an ominous presence. A cloud of fear. Fear exists in every crevice of every building. The shadow of him hangs so heavily, a man could suffocate for the need of air when he is near. Of all the wretched people I have encountered, none has stabbed my very soul as painfully as he. He is motivated, they claim, by God. What kind of a God calls for such cruelty, I will never know, but the Inquisition reigns with murder most wretched. And he has the supreme authority of the Inquisition.

The boy is not aware he is known to the cardinal; if he were, he is certain he would be dead, just as the others. It matters not from what class of society a person comes – be a man rich or poor, artist or clergy, all are vulnerable to the Inquisition. He has heard tales of the cardinal burning human bones after digging the bodies of dead heretics from the ground. Gruesome stories of the cardinal’s devotion to the rack, his affection for starvation and hot coals, but most of all, his Judas Cradle. The boy cannot say why, but the Judas Cradle is a thing more petrifying to him than anything else.

He follows the black cloak as it billows in the black night. It leads him close to the docks, and towards the only beacon of hope. Towards the promise of Cinfa’s doorway … Cinfa, the widow of the Inquisition; Cinfa, whose door is always open and welcoming to his heart.

New to him is this glowing, pumping longing, reverberating through his being. He will not be deterred because he has hope of a future different to what has been laid out for him. Hope of another, like himself.

Finally, he comes to the house, small and sure, with the pianoforte playing and the twinkling of drunk laughter emanating from within. He reaches out to the brass lion head of the door knocker. Once, twice, he bangs, pauses, then bangs a third time. He waits a heartbeat, then again bangs, one, two, pause, three. What can she, his only friend, be doing? She knows him; she knows his knock.

‘Cinfa, Cinfa,’ he cries, ‘open, please … I have news.’ Perhaps her voice is drowned out by the beating of his heart. How loud it must be in his ears, I swear I have heard it from the ten paces I run, hidden, behind him. ‘Cinfa, I know you are here,’ he cries into the doom of a rainy Seville night. ‘Jesus, look down on me, please. Open for me!’

Even God’s tears fall filthy on Spain. The city smells of blood and betrayal.

‘Cinfa, somewhere in the world I have a sister. Please, please, Cinfa …’ he cries more to himself now than the huge closed door. ‘A sister …’ he cries, until eventually he falls asleep on the cobbled paving in front of her door.

It is past midnight and the stars are barely visible through the filth and fog of Seville when the doorway is opened, and she appears, illuminated by the moon. Cinfa, Esther, the bearer of promise. Still, I gasp at the sight of her. Even after all her suffering, she is the most beautiful and radiant woman in all Seville, in all the world. She looks anxiously about the streets and I wonder, Is she searching for spies, or does she know I am lurking so close by? How I yearn to touch her as she crouches down next to him. I swear, just the sight of her will break my heart once more, would that I were him, would that she were so close to me. Esther, who stole my heart, Esther, who destroyed my life, how she flickers now as Cinfa, so charming in the moonlight.

Until this night, there has been nothing unusual about Simuel Henriquez Levi, although he does not yet know himself by that name. He is known still as Diego Rodriguez, a boy of his time, a child of the Inquisition, surviving on wits and courage.

Seville is filled with thousands of orphans like him, though few as resourceful. He is unrecognised by church or state, but it is better that way – to slip through life, unnoticed. Being recognised by the church is like the mark of death, unless you are one of them, and even then, so few survive Philip V’s wicked Spain. Never has he felt the need to excel or learn about himself, which is a blessing. I fear, had he known of his family before today, he might have felt special, might have felt even that the world had a want and role for him, which I know it does. But, so too, he is no fool; he would have known the extent of the danger he was in and, worse still, he would not have been silent. He would have searched and found her. Who can say if he would have survived this long? I have yearned to stride like Don Miguel out of the shadows and hear his voice close up, touch his cheek. But ignorance has kept him alive, and he has been protected – if not from the harsh realities of life, at least from the truths of his own life. He has never wondered from where he might come …

Not until now, the day of his thirteenth birthday. He knows it is his birthday because Don Miguel visits him at the shoddy orphanage only once a year, and this is every year the day. Always with a small gift: once, Don Miguel brought an orange from a foreign land. Every time, it has been a thing small and precious, but never could be kept beyond a week. The visits are brief and taken up more by prayer than conversation. But this year, the thirteenth year of his life, Don Miguel came with tidings of a difference. He came with a gift of an entirely different nature, word that would change the boy’s life forever.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Penguin Random House SA Rahla Xenopoulos The Season of Glass