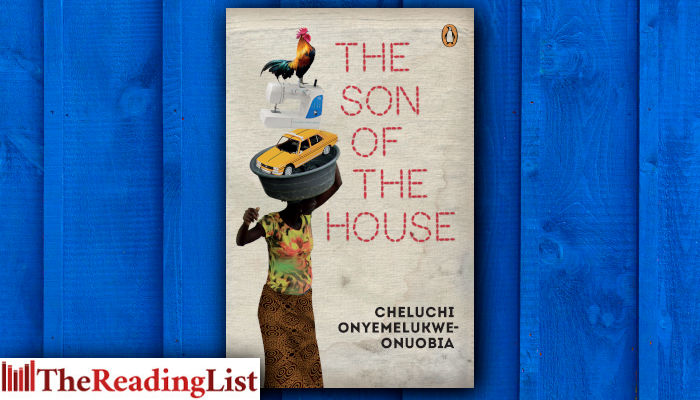

‘Only sons could carry the family name’ – Read an excerpt from Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s debut novel The Son of the House

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from The Son of the House, the debut novel by Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia.

About the book

In the city of Enugu in the 1970s, young Nwabulu dreams of becoming a typist as she endures her employers’ endless chores. Although a housemaid since the age of 10, she is tall and beautiful and in love with a rich man’s son.

Educated and privileged, Julie is a modern woman. Living on her own, she is happy to collect the gold jewellery love-struck Eugene brings her, but has no intention of becoming his second wife.

When dramatic events straight out of a movie force Nwabulu and Julie into a dank room years later, the two women relate the stories of their lives as they await their fate.

Pulsing with vitality and intense human drama, Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s debut is set over four decades in Nigeria, and celebrates the resilience of women as they navigate and transform what remains a man’s world.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

I liked the way my father confided in me and entrusted responsibility to me. It made me feel close to him. And so, although I had a deep love for my brother, taking care of him was special because it was something I could do for my father. And I knew this was something important to Papa because, after my brother, my mother had three more girls before her womb seemed to shut up shop, thus leaving my brother an only son for several years. Only sons could carry the family name, could make sure that the name of the family did not get lost.

‘See, your name is Afamefuna,’ Papa would say to my brother. ‘Your other name, Ugonna, the one who will bring honour to his father, carries a similar weight. I have not failed my parents. I know that you will likewise not fail me, not fail the honourable name of our family. And when the time comes, you, and your brothers, should it be God’s will to send us more, will carry on the great legacy of our family and pass it on to your own children.’

Afam, diminutive for Afamefuna – ‘may my name not be lost’ – that was my brother’s name. When more boys did not come along immediately, the name became even more significant. His academic strengths and his growing height boded well for the responsibilities that rested on his shoulders. His penchant for fun and frivolity did not.

My father would call him for special sessions on our family history. Whenever possible, when I had no work to do for Mama in the kitchen, I would slip outside to listen. We would sit on a mat in front of the kitchen, Papa cleaning his ear with the tip of a cock’s feather and our mother peeling egwusi, the darkness lit by the glow of the hurricane lamp and the moonlight. The bright light of electricity would have disturbed the intimacy of the evening; over time, in Umuma, hurricane lamps gave way to kerosene lamps and only occasional electric lights, and then to rechargeable lamps, and then to noisy generators.

My father had a lot of stories, and his deep voice was filled with spellbinding emotion – by turns joyful, sad, angry, but never passionless. Sometimes, it was about adventures in foreign lands, like the war in Burma. Other times, it was about our family. How our ancestors had worshipped the old gods, and how our father, one of his father’s two sons, had run away from the ichi ceremony. Igbu ichi was that painful branding and scarification of the face, which formed lines that crisscrossed on the forehead. In those days, it was done to sons of noble families, starting with the eldest, to distinguish them as members of the prestigious society of Nze na Ozo, a society of men who upheld truth.The hot iron seared into the forehead while the young man, in a show of the strength given him by his chi, bore the pain with only occasional short grunts.

Papa had joined the Catholic Church, risking my grandfather’s grave displeasure. As an adult, it occurred to me that he might have considered priesthood had it not been for the family traditions and the need to ensure that the lineage went on. Papa’s own father must have done much etching and imprinting of custom, of family pride and history. For Papa was a staunch Catholic, but also a firm believer that family lineages must be continued. As we grew up, he often said, as frequently as he could find a child to listen, that we should know where we came from. He would often say,’I am a Christian. But one has to protect one’s legacies. That is one’s heritage. Otherwise life becomes meaningless and vain, as the wise author of Ecclesiastes says.’ He would pause and look intently at Afam, who always looked past him. My own eyes always stayed on Papa’s face, drinking in his words and stories of who we were.

‘By joining the church and getting an education,’ he continued, ‘I brought light to my family. It is the duty of each new person in the line to bring something good to the family, to keep the family going.’

I was proud of my father’s contribution to the family line. When farming and old titles were becoming things of the past, our family stood in the new world as respected people – catechists, teachers, headmasters, civil servants, politicians.

‘Do you understand what I am saying to you?’ my father often asked Afam when he ended one of his stories, peering at him through the dim light of the hurricane lamps.

My brother would say yes, although he had been pinching me in the dark, playing, not taking my father too seriously, trying to get me to do the same.

‘That’s my boy,’ said my father, approval and love on his stern face.

I would make a better son of the house, I sometimes thought. But what fell to me was not carrying on the family name but ensuring that the one who was to do so succeeded.

Categories Africa Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia Penguin Random House SA The Son of the House