‘Mr Moloto, you know that farm is not really yours …’ Read an excerpt from Land of My Ancestors by Botlhale Tema

More about the book!

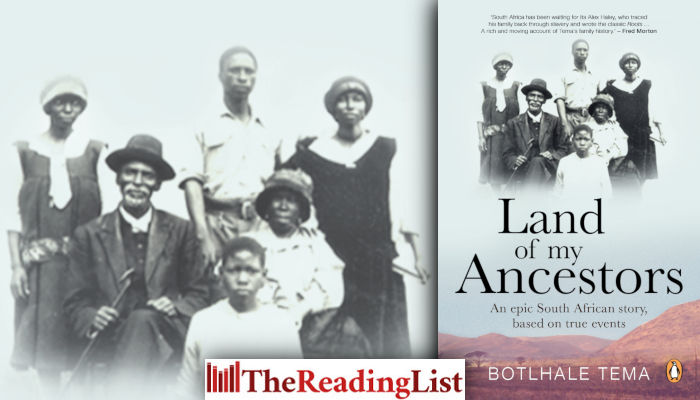

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from Land of My Ancestors by Botlhale Tema.

About the book

When working on the UNESCO Slave Route project in the early 2000s, Botlhale Tema discovered the extraordinary fact that her highly educated family from the farm Welgeval in the Pilanesberg had originated with two young men who had been child slaves in the mid-nineteenth century. She pieced together the fragments of information from relatives and members of the community, and scoured the archives to produce this book.

Land of My Ancestors, previously published as The People of Welgeval, tells the story of the two young men and their descendants, as they build a life for themselves on Welgeval. As they raise their families and take in people who have been dispossessed, we follow the births, deaths, adventures and joys of the farm’s inhabitants in their struggle to build a new community.

Set against the backdrop of slavery, colonialism, the Anglo-Boer War and the rise of apartheid, this is a fascinating and insightful retelling of history. It is an inspiring story about friendship and family, landownership and learning, and about how people transform themselves from victims to victors.

A new prologue and epilogue give more historical context to the narrative and tell the story of the land claim involving the farm, which happened after the book’s original publication.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

By the time Davidson took office in Bophuthatswana, the consultants were ready with their findings for economic development. By a nasty twist of fate, Davidson was appointed deputy minister for economic development, and the consultants identified the scenic Pilanesberg as the most profitable area for development.

Like those who had come before them, they stood in awe of the twisted mountains and fertile valleys of the region; they marvelled at the rocky outcrops and patches of granite spills; and admired the thickets of karee, wild olive, Mongela and Mmilo trees that covered the area, setting it apart from the rest of Bophuthatswana.

Apart from its beauty, the Pilanesberg area was centrally located and in close proximity to the potential tourism market of the Johannesburg metropolis. Situated in the centre of a one-hundred-millionyear-old volcano, one of the largest of its kind, the Pilanesberg mountains also had unique geological features, which could provide a range of habitats for different types of animals.

But the area also had potential of a less natural variety. Gambling was banned in South Africa, and any citizens with disposable income and a love of the casino frittered their money away in the nearby state of Swaziland. And so a local gambling niche was also identified in the homeland. The team recommended the establishment of a holiday and gambling resort for tourists and a game conservation park in the area.

The Bophuthatswana government teamed up with property developer Sol Kerzner, who established the resort of Sun City, while the government developed the Pilanesberg game reserve alongside.

The government bought out all the farmers in the valley and negotiated the incorporation of Welgeval into the game park. A royalty agreement was drawn up with Chief Pilane of the Bakgatla, who now possessed the title deed for Welgeval. The chief agreed to the deal, as the project seemed to hold significant economic benefits for the Bakgatla. In the flurry of development, the age-old agreement for the Welgevalers’ continued stay on the farm was swiftly forgotten.

Davidson was slapped right in the middle of a dilemma – his new job on the one side, and Welgeval, his home, on the other. We can only imagine his reaction at the presentation of the findings.

‘Let’s not do it there,’ he declared. ‘My people live in that area.’

‘Gentlemen, we must not get personal about these things. Think about the development of our people, the people of Bophuthatswana.’

‘But my people have lived there for generations.’

‘Mr Moloto, your people will be compensated for the houses they have built. Besides, they will be moved to an area near the budding town of Mogwase. We already have incentives and a tax-break programme that will bring factories and all sorts of industry to the area. Your people will get jobs and they’ll be able to educate their children.’

‘But it’s not just about the houses we’ve built …’

‘Mr Moloto, you know that farm is not really yours …’

In the month of June 1980 the Bophuthatswana government sent out emissaries to deliver notices of removal to the farm’s inhabitants, and all the Welgevalers were summoned from the various corners of South Africa to come and pack up their belongings and collect their animals. Later in the month, a government messenger arrived once again, this time to deliver envelopes containing minimum compensation for the houses that now stood ready to be destroyed. In rebellion against relocation to an area of the government’s choice, some people moved to villages of their own selection.

Finally, one Thursday morning in August 1980, government lorries rolled in to finish off the removal. Those who had stayed until the end watched as the vehicles lumbered up to the highest point of Welgeval and pushed their way through the Malau family residence, which was situated above the other houses.

The people of Welgeval gathered round to witness the destruction brought on to them. Women cried and clung to each other as the walls tumbled down. To avoid their own emotions, the men impatiently called them to pull themselves together and help load furniture onto the lorries. Officials in blue overalls handed out tents after each house was demolished.

The bulldozers worked their way down the slopes to the flat land, leaving piles of rubble in their wake. The church and the school at the centre of the farm were the next to fall, leaving only the modest monument built for the centenary of Gonin’s arrival. This sent out stronger shock waves than the demolition of the homes. These buildings had housed all of Welgeval’s memories – every important event took place here. The big wild olive tree stood lone once more, stripped of its holy status, just as it had been in the beginning before all these people had arrived.

The Welgevalers watched to see if the mighty bulldozers would head for the graveyard across the river where Polomane, Christina, Ryk Kerneels and all the first inhabitants were buried. But their appetite for dust was satisfied and they crawled back whence they came.

Early that evening, lorries packed with furniture, small animals and women trundled out of Welgeval, the hills throwing back at them the din of screaming pigs and barking dogs.

‘Kom, Swartland!’

A man cracked a whip to urge the cattle out of Welgeval for the very last time.

~~~

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Botlhale Tema Land of My Ancestors Penguin Random House SA