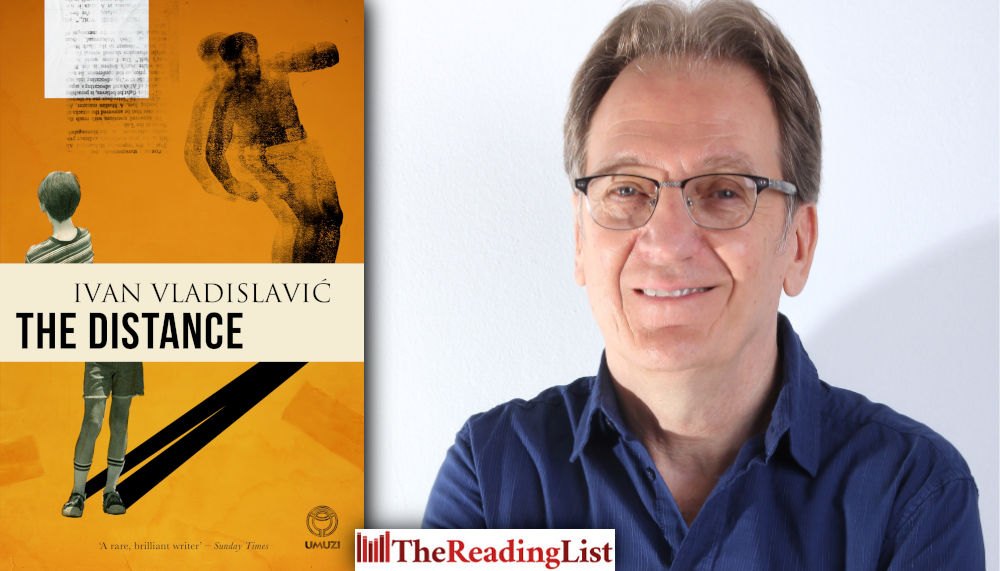

‘In the spring of 1970, I fell in love with Muhammad Ali.’ – Read an excerpt from The Distance, the new novel from Ivan Vladislavić

More about the book!

Penguin Random House has shared an excerpt from Ivan Vladislavić’s latest novel The Distance.

This is an intricate puzzle of a book by a writer of lyrical power and formal inventiveness. Against a spectacular backdrop, the heyday of the greatest showman of them all, Muhammad Ali, Vladislavić unfolds a small, fragmentary story of family life and the limits of language. Meaning comes into view in the spaces between then and now, growing up and growing old, speaking out and keeping silent.

Read an extract:

~~~

Joe

In the spring of 1970, I fell in love with Muhammad Ali. This love, the intense, unconditional kind of love we call hero worship, was tested in the new year when Ali fought Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden. I was at high school in Verwoerdburg, which felt as far from the ringside as you could get, but I read every scrap of news about the big event and never for a moment doubted that Ali would win. As it happened, he was beaten for the first time in his professional career.

It must have been the unprecedented fuss around the Ali vs Frazier fight that turned me, like so many others who’d taken no interest in boxing before then, into a fan. ‘The Fight of the Century’ was one of the first global sporting spectacles, a Hollywood-style bout that captured the public imagination like no sports event before it. In the words of reporter Solly Jasven, it was as significant to the Wall Street Journal as it was to Ring magazine, and it generated what he called the big money excitement.

I don’t know what I thought of Ali before the Fight of the Century, but I came from a newspaper-reading family and had started reading a daily when I was still at primary school, so I must have come across him in the press, and not just on the sports pages. In March 1967, after he’d refused to serve in the US army, the World Boxing Association and the New York State Athletic Commission had stripped him of his world heavyweight title. This was big news in South Africa, but I cannot say what impression it made on my nine-year-old self.

Although Ali was absent from the ring for more than three years, he was not idle: he was on the lecture and talk-show circuit, he appeared in commercials, he even had a stint in a short-lived Broadway musical called Buck White. In short, he was doing the things celebrities of all kinds now do as a matter of course to keep their names and faces in the spotlight and build their ‘brands’. He went from the boxing ring to the three-ring circus of endorsements and appearances. He was also speaking in mosques and supporting the black Muslim cause. But very little of this activity, whether meant in jest or in earnest, was visible from South Africa.

In 1970, when I was twelve, a Federal court restored Ali’s boxing licence. His first comeback fight was against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta and he won on a TKO in the third round. Six weeks later he beat Oscar Bonavena and that set up the title fight against Frazier in March the following year. It was a match Frazier had promised him if his boxing licence was ever returned.

We had no television in South Africa then and our news came from the radio and the newspapers. The Fight of the Century produced an avalanche of coverage in the press. My Dad read the daily Pretoria News and two weeklies, the Sunday Times and the Sunday Express, and so these were my main sources of information. In the buildup to the fight I started to collect cuttings and for the next five years I kept everything about Ali that I could lay my hands on, trimming hundreds of articles out of the broadsheets and pasting them into scrapbooks. Forty years later, these books are spread out on a trestle table beside my desk as I’m writing this. Let me also confess: I’m writing this because the scrapbooks exist.

The heart of my archive is three Eclipse drawing books with tracing-paper sheets between the leaves. These books have buff cardboard covers printed with the Eclipse trademarks and the obligatory bilingual ‘drawing book’ and ‘tekenboek’. In the middle of each cover is a hand-drawn title: ALI I, ALI II and ALI III. The newsprint is tobacco-leaf brown and crackly. When I rub it between my fingers, I fancy that the boy who first read these reports and I are one and the same person.

Branko

I am the sportsman in the family. My brother Joe doesn’t mind kicking a soccer ball around in the yard, but when I need him to keep goal while I practise my penalties he’s got his nose in a book. Now all of a sudden he’s a boxing fan. Not that I’ve seen a lot of boxing myself. I’ve been to a couple of Golden Gloves tournaments at Berea Park with my cousin Kelvin, where they put up a ring on the cricket pitch in front of the grandstand. But we prefer the rofstoei in the Pretoria City Hall.

The thing about wrestling is the rules are easy to understand. If Jan Wilkens is on the bill, you know he’s going to win. He’s a huge Afrikaner and he’s the South African champion. Kelvin always shouts for Wilkens. My guy is Rio Rivers. He doesn’t often win but he puts up a good fight. The last time my cousin and I went to the wrestling, Dad insisted we take along Joe and Rollie – that’s Kelvin’s little brother. It was a fiasco. Joe started rooting for Sammy Cohen. Sammy’s a pile of blubber in a black leotard. He looks like he hasn’t slept for three days and he always loses. That’s his part to play. Joe doesn’t get the principle: you’re not supposed to support the bums.

And now this thing with Ali. It comes over him like the measles. The boxing bug is going around because of the upcoming fight between Ali and Frazier. Naturally I support Smokin’ Joe. I would support him in any case, but the fact that my little brother has picked the other corner is a bonus. Another chance to get under his skin.

Joe Frazier’s going to give Cassius Clay a boxing lesson, Dad says. He’s going to knock seven kinds of crap out of that loudmouth.

Eight kinds, I say.

And Mom says, Watch your mouth. Even though eight is just a number.

Dad won’t say Muhammad Ali. Over my dead body. It’s always Cassius Clay. It drives my brother to tears of frustration. Sometimes he goes out in the yard behind the servants’ quarters and smashes tomato boxes with a lead pipe.

Sport is my thing and I wish he’d leave it alone. My plan is to win the Tour de France one day. I prefer road racing but I join the track season to keep fit. Cycling is not a popular sport. If we’re lucky fifty or sixty riders turn up at the Pilditch track in Pretoria West on a Friday evening, most of them seniors, and a handful of us in the schoolboy ranks. Juveniles, they call us, a stupid term you would never apply to yourself. The stands are nearly empty: the wives and girlfriends and mothers cluster together in a few rows with crocheted blankets over their knees. Ten rows back Joe is sitting alone under the icy corrugated-iron roof, wearing a knitted cap with an enormous pompom. He’d rather be at home but Dad says: You boys have got to stick up for one another. When the starter’s pistol goes or the timekeeper rings the bell for the last lap, he pretends to watch. He’s half interested in the Devil-Take-the-Hindmost because of the name, but mainly he’s reading a book in his lap, struggling in his black leather gloves to turn the pages of The Canterbury Tales or David Copperfield. The explosive pompom, the biggest one Mom ever made, hovers over his head like an unhappy fate.

When I go to bed, I find him shadow-boxing. He’s supposed to be sleeping, but he’s got the desk lamp swivelled to cast a shadow on the wall next to the window. Bobbing and weaving, he says.

Ja, I say, float like a bumblebee.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Ivan Vladislavic Penguin Random House SA The Distance