‘I wrestled with life and lost.’ – Read an excerpt from Nthikeng Mohlele’s novel Rusty Bell

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Nthikeng Mohlele’s novel Rusty Bell.

Rusty Bell was first published in 2014, and was republished in a new edition by Jacana Media in 2018.

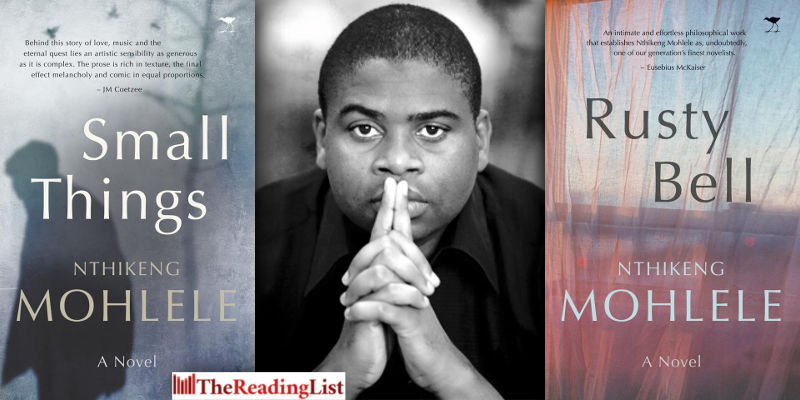

Mohlele was partly raised in Limpopo and Tembisa Township, and attended Wits University, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts in Dramatic Art, Publishing Studies and African Literature. He is the author of a number of critically acclaimed novels: The Scent of Bliss (2008), Small Things (2013), Rusty Bell (2014), Pleasure (2016), Michael K (2018) and Illumination (2019).

Pleasure won the 2016 University of Johannesburg Main Prize as well as the 2017 K Sello Duiker Memorial Prize. It was also longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award.

About the book

‘I wrestled with life and lost.’ So begins the story of Michael, a corporate lawyer known to his colleagues and associates as Sir Marvin, who picks his way – sometimes delicately, but more often in his own blundering way – through the unfathomable intricacies that make up a life: love and anger, humility and ambition, trust and distrust, selfishness and selflessness.

A flawed individual with an acute understanding of the roads that must be navigated to achieve even the slightest insight into the human condition.

In this study in introspection, embroidered with lyrical prose and astonishing intuition, the hero, meditative and melancholic, is at once both tragic and comic.

‘An intimate and effortless philosophical work that establishes Nthikeng Mohlele as, undoubtedly, one of our generation’s finest novelists.’ – Eusebius McKaiser

‘Mohlele’s voice is novel and shows a concern … for beautiful language for its own sake.’ – Percy Zvomuya

~~~

Read the excerpt:

1

Desirable Horses

I wrestled with life and lost. Not completely, but enough to still have to lie on Dr West’s couch every second Friday of the month for the last twenty years. Apart from the occasional long face, in the privacy of my study I am no different from any 48-year-old in any corporate law firm anywhere in the world. I get paid obscene amounts to sniff out loopholes in contracts, litigation minefields that if not detected could obliterate our clients many years in the future. I am a legal soothsayer of sorts, though my formal job description is transaction advice for multinationals. As senior partner, with an ex-officio board seat – for my risk-management skills, I am told – my workload is proportionally related to my six-figure pay cheque, less executive incentives and performance rewards.

My office at Thompson Buthelezi & Brook Inc. is large and tastefully furnished, in oaks and rare artworks. I put in adequate hours, am diligent, keep away from corporate gossip and office entanglements: some of the female colleagues are flirty and beautiful; the CEO, Bernard Parker, tells sexist jokes. My job’s all right; I meet interesting people, most of whom say I am one of the best in the business. The work itself is not rocket science, its essence rather straightforward, actually: firmly and officially advise corporates on how to make the most money, without getting burnt. That is not hard. I am busy with a Swedish-Namibian Telecoms merger as we speak: a 60:40 revenue share model. Nothing complicated.

I have a team of young lawyers working for me. I have never met with them, because my instructions are carried out by their bosses, who tell them what to do. Most of their work is good, sometimes average; seldom brilliant. I can tell when my instructions have been diluted, misrepresented – but the slippages are easily fixed: presentation of a Sony cassette to the senior attorney in question, onto which I voice record all my instructions without fail. Located at the heart of the Sandton CBD, TB & Brook Inc. is surrounded by what economists call ‘big money’ – insurance, banking and mining companies. My office patio overlooks the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, evidence of the ultra rich trapped in a warped bubble.

*

My name is Michael. Everyone at the office calls me Sir Marvin. I am the splitting image of my father, who for most of his life had people freezing in their tracks, thinking Marvin Gaye had risen from the dead. Home is in Morningside, eight minutes from work, five if I take the BMW M5. I cannot arrive late at meetings; it is not expected of me to be late – lateness is a disease for other people. I live with Rusty, my lovely wife. Michael Junior, our only son, has recently moved into a penthouse his mother bought him, where I hear they have all-night parties with questionable girls. I let my father speak to him, or my mother, because they understand him better. He has a thing for white girls and chewing gum, something I find rather strange. The chewing gum, I mean.

I have been having a lot of trouble with Michael Junior, although I have to say that some of that abated following his brief incarceration on a drunk-driving charge: shock treatment. I had taken the afternoon off, at Dr West’s rooms, when he called, barely audible, the 550i completely written off. That was the firm’s BMW and, with insurance not budging, I offered to replace it with an identical car. I drove to the scene, found him reeling with and reeking of alcohol, walking around in his underpants, dictating to paramedics and traffic enforcement officers that he was the son of a respected lawyer, which was true, and that his father would be very upset if they did not let him go, which was false and infuriating.

He could have posted bail the next day, a Thursday, but I insisted that not a soul lift a finger until the following Tuesday, so he had four days to sober up and think about his life. There are times I wish I had such time; the opportunity to completely alter the course my life has taken. ‘You let those thugs, those murderers almost kill me!’ he yelled at me on his release and didn’t speak to me for eight months – except when he wanted money, of course. Rusty played the diplomat, committed to both sides and yet to neither. I believe he has those parties to spite me, dare me, punish me for things his mother tells him in conspiratorial tones, especially when she is insecure in her diplomatic role, when she is angry with me, when she intentionally serves me burnt toast.

There was a time, years ago, when Rusty loved me. She is, strangely, part of the reason I continue to see Dr West, but not the sole reason by any means. Catherine and Abednego, her parents, are old and sickly – and no longer visit every five minutes. I don’t hate them; I just don’t like them. Catherine tries, but she is married to a fatally flawed man who is domineering and has opinions on everything – the swine. Three visitor bathrooms, but Abednego will pass them all and stink out my private loo, off my bedroom.

I regularly came home to suffocating smells, until I realised without being told that it was Abednego perching that wobbly rear of his on my loo, door wide open, filling in horse-racing crossword puzzles. I was, in the end, the unreasonable one, unwelcoming, unfriendly.

I pleaded. ‘Can’t your father use the visitors’ bathroom? Please, Rusty.’ She sulked, became reckless with the dishes in the sink, and took the M5 keys without asking, leaving me to drive that lumpy piece of metal, her Hummer 3.

I looked like I was driving through a war zone in that thing, tank like, with small side windows, like I was dodging sniper bullets. It was embarrassing parking that monstrosity at important meetings, graced by executive saloons – having to explain my sudden change in vehicular taste. But I digress.

*

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media Nthikeng Mohlele Rusty Bell