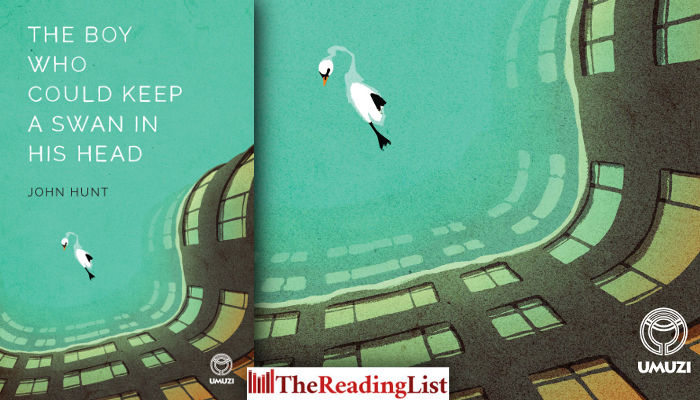

‘Hillbrow, 1967. The New York of Africa.’ Read an extract from John Hunt’s new novel The Boy Who Could Keep a Swan in his Head

More about the book!

Umuzi has shared an excerpt from The Boy Who Could Keep a Swan in His Head, the new novel by John Hunt.

Poignant, witty and wise, The Boy Who Could Keep a Swan in His Head is a meditation on being alive and shows us the power of books when we need them the most.

Read the excerpt:

Hillbrow, 1967. The New York of Africa. Apartheid kept the roads clean and the rubbish collected. There were buildings going up everywhere – “lickety-split”, according to Mr Trentbridge. Large chunks of tin-roof houses were found in skips almost every day as the boy walked home from school. These homes were recently surrounded by honest gardens and the occasional peach tree. Someone wrote in The Star newspaper that soon Hillbrow would have more people per square kilometre than Tokyo. Everyone quoted that article to everyone. Some even cut it out and kept it folded in their wallets.

The boy, who went by the name of Phen, lived in Duchess Court. You’ll find it at 20 O’Reilly Road, Berea. Technically it’s in Berea, but for all intents and purposes it’s Hillbrow. The heartland of Hillbrow, the parallel streets of Kotze and Pretorius, is barely a three-minute amble away. Duchess Court was built in the twenties, solid and grey with flirty bits of art deco. When first constructed it must have dominated the skyline. By the time Phen moved in, though, it had the look of an old, stout woman in a sombre overcoat that had been mended too often.

Not that the building was without its charm. At its core was the wood-panelled lift with its bevelled mirror, known to all simply as Mr Otis. He waited at the end of the foyer with three cast-iron ladies above his lintel. Joined together, they danced in a chorus line with their right legs held scandalously high. If you opened the heavy wooden door, then slid back the metal gate, the lift would take you a clanking six storeys high. The grill, when concertinaed closed, left big gaps you could peer through. As you faced forward the lift shaft was presented in vertical grey strips that drifted upwards in a slow-motion blur. This was punctuated by six square bursts of yellow if you went all the way to the top. The lift door at each floor had a small glass window allowing you to wave to people as you went past them.

Stopping was always a violent and inexact affair. Tenants would suggest to newcomers that they lean against the walls or, at the very least, hold on to the polished brass handle of the metal gate as the lift slammed to a halt anywhere between a foot and an inch away from the floor of your choice. The uninitiated would battle to see this as an arrival and presume something had gone wrong. It was only after the metal door had been brazenly slid open that they would sheepishly step up or down and then out.

Phen lived on the ground floor in number four. His trips with Mr Otis were therefore infrequent or for fun. And a fertile imagination grew more fecund when transport was on hand. There was a time when, based at military headquarters behind the washing line on the roof, he needed to find the V2 rocket base the Germans were using. London was taking a terrible pounding and it was all up to his commando unit. After days of relentless reconnaissance they found the cunning concrete shaft dug six storeys deep into the mountainside. Although they were vastly outnumbered, thanks to the element of surprise the mission was a total success.

If you sat on the bonnet of Mr Trentbridge’s Ford Cortina and looked at Duchess Court, number four was situated on the extreme right-hand corner. A palm tree, planted years ago, blocked out ninety per cent of the view from the balcony and stretched up to the fourth floor. Doves cooed high up in the fronds as if the tiny strip of green between the building and the pavement was an oasis. Phen often Lawrence-of-Arabiaed around that tree, offering dates and nuts in the form of Wilson’s toffees to the gathered Bedouin tribes. He would need their help if the Turks were to be driven out of the Middle East once and for all.

With a dishcloth on his head he blew up countless enemy trains as they moved through the desert and up O’Reilly Road. His plunger was a pencil he’d wedged into a hole he’d made in the top of an empty condensed-milk tin. As he rammed it down hard, the dynamite hurled the huge locomotives into the air. Volkswagens, Morris Minors, Fiats and the occasional Peugeot would launch helplessly off the ground and land on their sides and roofs.

“Tell your men not to waste ammunition, Sharif Nassir. There are still many battles to come for the Harith tribe.”

It was an easy yet pitiless business finishing them off. Hidden behind the garden wall, his sawn-off broomstick picked them off one by one. It wasn’t pretty but then war never was. He had to remind himself, “Mankind has had ten thousand years of experience at fighting and if we must fight, we have no excuse for not fighting well.”

The flat itself was bigger on the inside than it looked from the outside. He lived in a flat while all the new buildings around him contained apartments. That was typical of words; they changed without rhyme or reason. And when you asked why, no one could give you an answer. His flat wasn’t flatter. In fact, the older buildings had much higher ceilings. And those new apartments were built so tightly together they should be called closements. His father said flats came from Britain and apartments from America. He said those damn Yanks were getting in everywhere.

If you opened the front door to number four you could turn sharp left into the kitchen or proceed straight into the dining room. The kitchen floor was covered in one flat sheet of green linoleum that bubbled depending on where you stood. You could get the bubble to move but you could never get it to disappear. Much like trying to get the dent out of a ping-pong ball. Trapped air is happy to be transported, but, it will take its ballooned vacuum with it. Concerned visitors even suggested there may be a mouse problem in the kitchen. This, in turn, created such embarrassment for Phen’s mother that his routine job became to force the bubble behind the fridge before anyone came to visit.

Not that walking in the dining room was without its challenges. Like the rest of the flat, it was all parquet flooring in what used to be a very close-fit herringbone design. Over the years, the perpetual pounding of feet in the high-traffic zones had begun to take their toll. Like a piano with a number of loose keys, the initial appearance of a smooth surface was deceptive. If you stood on the tail of the wrong wooden slat, its head would pop up like a snake ready to strike.

The most dangerous square lay, innocuously, directly on the path to the lounge. All three hardwood planks were loose and sat next to each other at slightly different heights. If you were carrying a tray you never stood a chance. And if you were a brisk or heavy walker one of the three would often flip out completely and smack you on the shin.

When Phen had caught his mother crying, even though she’d said everything was alright, he decided to fix the floor in an attempt to cheer her up. He was a bit of a hoarder and went straight to the top shelf of his cupboard. Under his two neatly folded school shirts he fished out the OK Bazaars plastic bag. Beside the egg from two Easters ago and the strips of liquorice, now a deep emerald green, he found his stash of chewing gum. He wasn’t sure exactly how long to chew for. After the taste had left, was the stickiness gone too? He decided merely to make the gum moist then pull it out. Each piece was given a minute in his mouth. No more, no less.

He’d seen pictures of master craftsmen at work and tried to adopt their demeanour. He held the edge of the slats up to the light and frowned at their unseemly roughness. He traced his finger across the ancient lumps of bitumen, then took his mother’s metal nail file and made them smooth. He’d put a newspaper on the dining-room table to catch their falling flakes, but most fell gently into the fruit bowl. Once finished, each six-inch plank was lined up vertically on the sideboard like a row of dominoes. He was uncertain about how to apply the chewing gum. One long stretch? Or a series of blobs?

After experimenting with both, he decided on the blobs. The measured distance between each mound of gum seemed aesthetically more pleasing and carried a greater sense of purpose. It reminded him of his Meccano set where a series of aligned holes solved everything. This choice demanded more material and depleted his entire reserve. By the time he was finished, a three-year collection of gum lay beneath the dining-room floor. Most were Chappies so he kept the wrappers to read the jokes and Did You Knows printed inside. However, there was also the faint whiff of peppermint and spearmint from other gums. Phen felt proud and exhilarated when he was finished. There is a kind of satisfaction that seeps in when a job requiring physical labour is well done. It’s the sort of feeling that sustains you for quite a while even when no one else notices your handiwork.

On the south side of the dining-room wall was a door which opened into a cupboard that was so deep it was referred to as the storeroom. The three shelves at the back were packed with the finality of knowing no one was ever going to reach them. On the middle of the top shelf, bristling like a series of broken vertebrae, lay the deformed wire hoops of the record rack. Somehow on its journey in the delivery van from Shotley Residential Hotel, not even half a mile away, the leg of the sofa had been placed on its delicate spine. The wire channels were now splayed embarrassingly wide in the middle and impossibly tight on the opposite edges. South Pacific, Brigadoon, My Fair Lady, Gigi and all their contemporaries were therefore forced to lie on top of one other, flat and square. They, in turn, rested upon a hatbox from another age. Now empty, its circular velvet-covered lid captured the memory, if not the contents, of its beauty.

One shelf below, and slightly to the left, lay the likewise empty hamster cage that had once housed Philby. Phen had been allowed to buy the white hamster provided his father could name him. “That rodent should’ve been behind bars years ago.” Only much later he learned that Philby was a British double agent who’d defected to the USSR. Teeth marks could still be seen where the hamster had gnawed through the pale blue powder coating of his steel feeding tray. Phen had placed the cage there himself, in a solemn ceremony shortly after Philby’s demise. He hadn’t been sure where you put the homes of the dead, let alone the dead themselves. He had wanted to ask, but couldn’t find the courage. He sensed a plastic bag and the dustbin might have been the answer. When he’d returned from school, his mother had given him a hug, said she was sorry and now the subject was closed.

Which is why, two weeks later, when the hamster wheel began to run wildly deep in the darkness of the cupboard, Phen was at first confused and then elated. He’d read the stories and seen the pictures of the resurrection. He’d pored over those yellow rays that burst from behind dark clouds as white doves, caught in a whirlwind, spun up to heaven. He ran to the door and smote the darkness asunder. The huge black rat was clearly startled by the light suddenly flicking on. However, with size comes a certain confidence. He allowed himself a few extra whirls before darting out the cage door and through a pile of London Illustrated News.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts John Hunt Penguin Random House SA The Boy Who Could Keep a Swan in his Head Umuzi