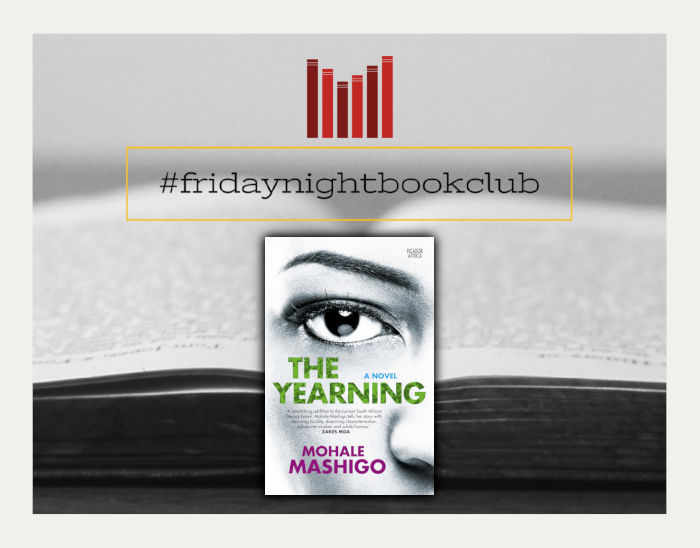

Friday Night Book Club: Read an excerpt from Mohale Mashigo’s award-winning debut novel, The Yearning

More about the book!

The Friday Night Book Club: Exclusive excerpts from Pan Macmillan every weekend!

Staying in this evening? Settle in with a glass of wine and this extended excerpt from Mohale Mashigo’s debut novel, The Yearning.

The Yearning won the University of Johannesburg Debut Prize for South African Writing in English, and was also shortlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award and the First-time Published Author South African Literary Award.

About the book

‘A bewitching addition to the current South African literary boom. Mohale Mashigo tells her story with charming lucidity, disarming characterisation, subversive wisdom and subtle humour.’

– Zakes Mda

How long does it take for scars to heal? How long does it take for a scarred memory to fester and rise to the surface? For Marubini, the question is whether scars ever heal when you forget they are there to begin with.

Marubini is a young woman who has an enviable life in Cape Town, working at a wine farm and spending idyllic days with her friends … until her past starts spilling into her present. Something dark has been lurking in the shadows of Marubini’s life from as far back as she can remember. It’s only a matter of time before it reaches out and grabs at her.

The Yearning is a memorable exploration of the ripple effects of the past, of personal strength and courage, and of the shadowy intersections of traditional and modern worlds.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

THE YEARNING

My mother died seven times before she gave birth to me. I am grateful for that corpse that somehow always seemed to resurrect itself. My father is gone but his smile is alive on my brother’s face. There is no life without death; the two rely on each other and we rely on them both for our purpose. A new mother knows her purpose when she holds her baby within her and in her arms for the first time. A man’s work has its purpose in death, as part of his legacy. Why then do we love the one and despise the other? Why do we sacrifice so much of the present to hide the past? Why do we take away the future’s knowledge of itself in order to make the past seem perfect? My brother only knows a father when he looks in the mirror. The Yearning haunts him. My mother turns away from the traditions of the past. The Yearning confuses her. I speak as only half of myself. The Yearning hurts me. The life in me came at the cost of another’s but I refuse to apologise for that. A part of who I used to be has vanished and I’m now faced with the possibilities of who I could be. The Yearning never stops till we embrace everything that brought us here. In our quiet denial, The Yearning devours us.

THE NAME

My grandmother often says she regrets giving me my name. ‘Children always live up to their names. And you did more than live up to yours.’ She shakes her head sadly and laughs as she says this. It is an unbelievably hot day in Soweto and Nkgono is on one of her rare visits to us. She has never been shy to share her dislike for Soweto. ‘My child ran away to be here. I don’t like this place. I never will.’ Nkgono was always laughing, even when saying things that seemed tragic.

‘Your mother was having a difficult pregnancy and you took a long time to arrive,’ she would tell me. ‘Such a stubborn child!’

I loved listening to my Nkgono tell the story of the day I arrived.

‘Your father had been driving like a crazy man. Your mother decided at the last minute that she wanted me with her. It was a long way back from Pietersburg and he didn’t want to risk missing your birth. I also wasn’t comfortable with my only daughter being left alone with that ngaka aunt Thoko of your father’s at such a time. That’s the reason I didn’t complain about his driving. Your Ntatemoholo had also wanted to be there, but I didn’t want my plants and animals left all by themselves. He was the only person I trusted with my plants.

‘Shelling peanuts was the only thing that kept my mind off how fast we were going. Jabu was anxious; new fathers always are. The silence hung between us until we pulled into the dusty yard of the four-roomed house your parents lived in.

‘Your mother Makosha was sitting on the stoep, grinding away at a stone with her teeth. My poor daughter − she looked absolutely uncomfortable with a fully baked baby inside of her. We thought for sure you were going to be a boy, because of the way she was so ugly. Thoko was boiling something smelly in the kitchen, so I sat out on the stoep.

‘”Ma, I’m scared.” That was all your mother said to me. Thoko stopped staring into the brewing smelliness and came over to greet me: “This grandchild of ours wants to stay the entire ten months.” Jabulani busied himself with carrying my bags into the second bedroom, while we mocked Kosha about how ugly you were making her.

‘The Soweto people were complaining that it was too hot; I live in the heat, grow food in it and have even raised a child under that relentless sun. Thoko said it would rain soon. There was not a cloud in the sky but I believed her. Your mother had just started her garden. The sun was not allowing it to flourish. “There hasn’t been rain in weeks. That is rare for Joburg summer,” was Makosha’s explanation for the state of her sad garden.

‘Thoko brought Makosha the smelly brew in a cup and sat down next to me. The three of us just sat there staring at the pathetic garden in silence. Thoko looked at me and said, “I was telling Makosha that Jabulani can help the baby come, but she doesn’t believe me.” I smiled because Makosha hated talking about sex with me. She knew exactly what my response to Thoko’s statement would be. “Oh please, Mam’Thoko don’t get my mother started,” she said, with red gravel in her mouth. She craved the taste of earth more than anything when she was pregnant with you. I smiled and pulled peanuts out of my pocket. Thoko was saying exactly what I had told your mother. Just before your father came to fetch me I was telling one of my neighbours that sex was what would bring you into this world a lot faster than anything else. Sex brings babies into the world all the time.

‘”Ma, the nurses at the clinic told me that I must just walk and that will help.”

‘”Walk to where? You trust the nurses over me, even when thousands of mothers have trusted me with their daughters?”

‘”Hai Maria, you know children never trust their parents,” Thoko said, signalling to her daughter-in-law to drink the concoction. Makosha put the cup down and tried to stand up. Her dress was wet.

‘”The baby is coming … Jabu!” Eehhh this child of mine! Sitting with women who are there to help her deliver and she calls out for her husband. Jabu came running out of the house but Thoko waved him away and helped me take your mother into the bedroom. Hooo the scene your mother made! She was crying for her husband, acting like she was the first woman in the world ever to give birth. Thoko grabbed hold of her face and looked her in the eyes. “This is not a man’s place. Those pains are going to get worse but you and your baby know exactly what to do, sisi.” That seemed to calm her some. I was standing by the window in the second bedroom that Thoko had prepared for us to sleep in. “Don’t worry, wena Thoko, that stubborn child is not coming any time soon. Let Makosha shout until she can’t.”

‘Eventually your mother stopped crying and we told her exactly what was going to happen. Things she had already heard but was suddenly fearful of. What happened next is something nobody can explain. I knew you were ready to emerge, and the room suddenly grew dark. Thoko stood by the window and said it was starting to rain. There is no way of knowing this for sure, but I felt the rain hit the ground the same moment you crowned. The stubborn baby turned out to be a girl. Your mother took one look at you and started crying again. You had finally arrived and you were alive, breathing, screaming, humming and beautiful.

‘I always tell people that you just slipped out with no fuss and nonsense. Your mind was made up and you stepped out with nothing but the past behind you. You looked like a queen from an ancient civilisation, so regal and certain. That’s why I gave you that name: Marubini. You were a new beginning for us who had lived long lives and needed respite. Marubini is where our past lies, the place of old from where we once came. You emerged and brought us into the future. Thoko loved the name and nobody objected to me giving you that name. Jabu wanted his first child to have only one name and that’s why we didn’t give you a “school” name too.

‘Your father, Marubini … what an incredible man. Jabu never doubted himself. Once his mind was made up there was no discouraging him. Heh, he is the person who brought my child back to me! Ei, your mother was so troublesome you know? She just left home. Did what all girls who have too much power and not enough sense do: ran away from what she thought was the problem. Then one day she stepped out of your father’s car, unsure whether we would welcome her back. Well, you know Peter doesn’t know how to stay angry. He was just glad that his only daughter was back home finally.

‘Jabulani introduced himself and said he was returning our daughter to us so one day he could ask for her to be his wife. That day you were born, you wouldn’t stop crying once you had started. But when your Mama held you, then you stopped. The past was really behind us. Everything changed once you were born. The summer rains fell and Makosha started paying attention to her garden. That same garden that was dry and dying … The rain that you brought with you revived the garden and your mother’s love for gardening.’

I can’t say for sure how much of Nkgono’s story is true. But I liked hearing it. Every year on my birthday, she still calls to tell me the story of how her daughter gave birth ‘to a beautiful but stubborn granddaughter’. We all have the desire to be special. The story of my birth made me feel extraordinary. I was born and I revived my mother’s love for gardening. The little garden that was saved by my rain became her florist business that kept our family alive. I am blessed to have matriarchs who hold their own even when the ground falls from beneath their feet. But even the sturdiest trees fall if the wind is strong enough. My father’s death devastated my mother and the child she was carrying at the time. Her ability to cultivate couldn’t save her garden. It seemed like every tear that was shed took life out of the plants and vegetables in our backyard. The soil dried up and nothing grew there again while we lived in that house. Luckily my little brother didn’t suffer the same fate as the garden. As soon as Simphiwe was born, I felt like he was mine. That may seem a strange sentiment for a little girl to have, but it was obvious that Ma didn’t want to get too close to him, not in the beginning. He came out light yellow-brown like my father, not deep brown like me and Ma. He was too much of something she had lost. So I helped Gogo Thoko look after him while my mother went to work, or lay in bed looking out the window.

Even though she kept him at a cautious distance, I knew Ma loved Simphiwe. Sometimes when she came home from work she would sit down in the kitchen and just hold him; smell his hair and kiss his little fingers. Gogo Thoko would spend the day with Simphiwe while I was away at school. My first years of school were horrible. I cried most mornings because I just wanted to be at home. I was so used to spending week days at home with my Ntatemoholo, my mother’s father. While other children were at crèche, I was with my grandfather. Gogo Thoko said that it was okay to cry because I had lost my grandfather and father in such a short space of time. ‘Kodwa, the crying has to stop eventually, Marubini.’ I really didn’t want to cry. In the evenings I was content to wait for Ma to fetch me at Gogo’s house after work. Then we would take a taxi home and Ma would have her time with Simphiwe in the kitchen, kissing his fingers and counting stars on his toes. She would put him on her back and go outside to work at reviving her garden.

The house was very quiet when Ma and Simphiwe were in the garden. The TV would be on but it may as well have been off because I couldn’t concentrate. I came to prefer the silence, just sitting and watching Ma outside trying very hard to get her garden back to its previous state. But it was futile. Baba died and so did the garden. All we had was sadness and anxiety. Ma went to bed with it and I woke up in its arms. I would be washing myself in a big metal dish while Simphiwe was getting his morning bath, all the while reminding myself that school was not a bad place and that Ntatemoholo and Baba would not like to know that I was crying for no reason. As soon as the minibus taxi stopped outside my school the panic would set in. Lwambo was the man who drove the minibus that took me and the other kids to school and back. Everyone was used to my tears by now so they just ignored me. I didn’t mind because I craved to be left alone. Ma would stand at the door waving until we turned the corner. The further we got from home, the sadder I became. By the time we arrived at the school I would be crying quietly. But the crying didn’t remain quiet for long. It became a full-scale meltdown as we were sitting down for the lessons to start. Ma enjoys telling Simphiwe how his sister ‘almost became a primary school dropout’ because the teachers were tired of my tears.

I don’t know why I’m thinking about these old things now. The words in the report I’m supposed to be working on have started blurring. At this point there is no use pretending any useful work will be done. My apartment is quiet, the TV off as usual. Muffled laughter and unfamiliar voices filter through the walls from next door; my neighbours seem to be having a dinner party. Fridays are a break from my usual steamed vegetables and fish dinners. The plan was for Pierre to come over but judging from the lack of communication he is probably working late at the restaurant again. How did a smart girl like me get stuck with a man who never has time for anything but work?

I sit alone at the table, thinking back to the day we met. I had just started my job at De Villiers Wines and everything was new. Not only was I feeling completely inadequate, but my colleagues were constantly questioning my presence. I had only lasted a year in advertising, in a job I had come to hate. That ivory-tower world made me feel far removed from people. The clients were okay, if you didn’t mind them throwing their weight around, reminding you that your job wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for ‘the budget’. It was the people I had to work with that finally made me quit. Most of them thought that taking a two-hour Township Tour that ended at a tourist-friendly drinking spot was a good way to get to know the ‘target market’. It didn’t help that all too often the ‘target market was me, my family and the people I knew. I grew tired of being accused of ‘overreacting’ and ‘reading too much’ into the crappy campaigns. My colleagues had stopped asking for my opinion, even on campaigns that I was involved with. They just couldn’t get why I would object to the fact that black people were portrayed dancing; why would they be dancing, when the advert was for tea?

One day during lunch break I just started looking for new jobs. There was no point in staying on in advertising; we weren’t meant for each other.

I didn’t know anything about wine when I applied for the vacancy in the wine farm’s marketing department. De Villiers Wine needed to put some ‘colour’ into their team, so they hired me. I spent two weeks following the wine from seed to bottle and distribution. Eyes and doubts followed me around the tiny office. All my preconceptions about people stomping grapes to make wine were shattered. Winemaking was actually a very technical and scientific business. I immersed myself in the world of wine. No time to eat or sleep much. I was working for one of the country’s oldest and most established wine farms. The pressure was beginning to consume me. It was the worst possible time to organise a birthday dinner for a friend.

‘Nobody here yet? Am I early?’ The birthday girl, Unathi, stood in the foyer, clutching at the hem of her party dress. Her long legs couldn’t keep still, shifting her weight from one foot to the other. As the designated organiser of this celebration, I smiled to show her that everything was going to be just fine. I didn’t blame her for sounding anxious. I’d arrived late because Stellenbosch is far away from Cape Town and I’d been locked into a late afternoon meeting that had gone on for far too long. Unathi was already there when I arrived. True to her usual panicky nature, the first thing that came out of her mouth was ‘Aphi ama-lady? Where is everyone?’

Unlike me, my best friend is super-organised. She’s the kind of person who doesn’t just remember your anniversary but sends you a reminder to get your partner ‘that thing he mentioned he wanted that day we met’.

‘Unathi, calm down, it’s not even 7.00 yet. They’ll be here. Some of us work for a living, you know.’

My stay-at-home-mom friend wasn’t at all hurt by my outburst. It just rolled right over her. We seated ourselves at the bar of La Cuisine, her favourite restaurant in Mouille Point. She ordered a fruity cocktail for herself and a glass of wine for me. An overly chatty waitress showed us to our table and my head started pounding; there were only four chairs at the tiny table. I had my back to the birthday girl but I knew she was wringing her hands. With my business smile fixed to my face, I explained the situation to Ms Chatty. She didn’t seem to understand the enormity of the error. Ms Chatty didn’t get the chance to do more than mumble inaudibly before she was cut off by my demand to see the manager ‘immediately!’ At this point Unathi was looking around nervously, suspecting, correctly, that I was about to make a scene. She moved closer to me and said, ‘Please, Rubi, don’t.’ I put my overloaded handbag down on the table and counted to ten, something Unathi recommended I should do whenever I felt that I was going to lose my cool.

I was on my seventh recount when a calming male voice greeted us: ‘Good evening, ladies, I’m so sorry about the mix-up.’ As soon as the voice appeared, things started to happen around us: tables were re-assigned, extra chairs brought up and in moments we were being led to our new, much bigger table.

Unathi was busy putting away the tissue that she had ready in her hand, just in case things went from bad to worse and she couldn’t control her tears; that girl is always prepared. I was looking back towards the door where our party had, thankfully, started to arrive when a hand was extended towards me across the table. It belonged to the owner of the calming voice, who turned out to be the owner of the restaurant too.

‘Hi, I’m Pierre; please let me know if you need anything else.’

I couldn’t quite place the accent. He handed me the handbag that I had left on the previous table.

‘Uh, are you wearing contacts?’ Unathi asked him in her tactless way, as if it was the most natural thing in the world. This made me take a closer look at him; and there they were, those green, gorgeous eyes, staring out at me from that caramel face. A perfectly chiselled face, the caramel rising at the cheek bones and dipping into beautiful craters that appeared when he smiled.

Unathi kept staring as he shook his head and answered the question he had probably been asked all his life. I couldn’t look away from him either; it was as if he had accidentally turned us into statues. Summer possessed my body and it seemed to have forgotten how to move. I could feel the pools of sweat forming inside my silk top. He didn’t look like he was trying to keep us there intentionally but there we were, the three of us; us staring at him and him smiling at us. He himself was stuck there too, trying to pull himself away from this process of turning our flesh into fire. Finally his gaze moved from us to the women arriving at the table, and he was able to escape in the distraction.

‘That was nice,’ Unathi sighed.

Nice indeed! All I could think about for the rest of the night was that delicious mix of caramel skin and gorgeous green eyes.

The intercom goes off; it’s the building security downstairs, informing me that I have a visitor. I tell them to let her up, knowing it’s Unathi. A few minutes later my best friend is standing in my kitchen, pouring herself a glass of wine. ‘Why didn’t you invite me over? Woo, it’s bad behaviour to drink by yourself, sisi.’

I just laugh.

‘Serious, Marubini.’ She’s smiling, though − I can tell from the way she says my name.

Nkgono says she regrets giving me my name. But I don’t think my name is the problem. The real problem is all the lies.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Friday Night Book Club Mohale Mashigo Pan Macmillan SA The Yearning