Find out more about Mhudi, the first novel by a black South African, in an excerpt from Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje

More about the book!

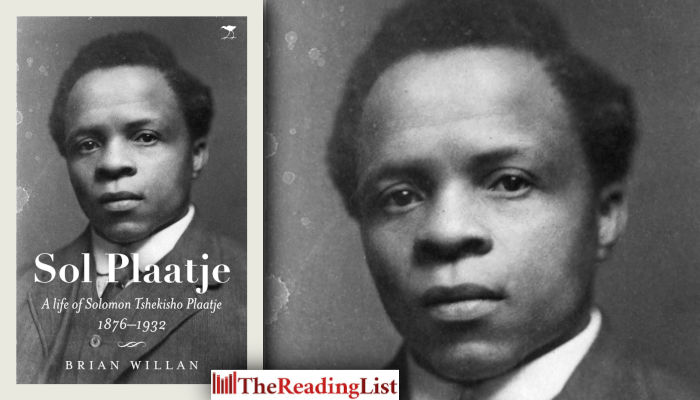

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876–1932 by Brian Willan.

This biography celebrates one of South Africa’s most accomplished political and literary figures.

Sol Plaatje was a pioneer in the history of the black press, and also one of the founders of the African National Congress in 1912.

He wrote a number of books, including – in English – Native Life in South Africa (1916), a powerful denunciation of the Land Act and the policies that led to it, and a pioneering novel, Mhudi (1930).

Mhudi was the first full-length work of fiction written by a black South African.

Click on the link above for more about the book.

It takes a historian who was invested many years in research to write a biography as detailed as this one. Willan relates Plaatje’s story with such amazing skill that this biography is a pleasure to read. It is as detailed as it is beautifully written in accessible language. – Sabata-mpho Mokae

Read an excerpt from the book:

~~~

Chapter 17

Mhudi

In May 1930 Plaatje wrote to his old friend Georgiana Solomon, now well into her eighties, the latest letter in what seems to have been a regular correspondence. His news was mixed. ‘We are not too well physically, Elizabeth and I, but thank God we are still alive and about our usual efforts.’ The children were all well. ‘They frequently congratulate me on having an English mother abroad who is constantly praying for my safety and the welfare of my family – especially when they read some of your old letters to us!’ The political outlook, he reported, ‘is not too pleasant’, but he had no wish to go into any detail, saying simply that ‘we live in hopes’, seeking solace in Samson’s biblical aphorism, ‘Out of the eater came forth meat and out of the strong came forth sweetness’.

In May 1930 Plaatje wrote to his old friend Georgiana Solomon, now well into her eighties, the latest letter in what seems to have been a regular correspondence. His news was mixed. ‘We are not too well physically, Elizabeth and I, but thank God we are still alive and about our usual efforts.’ The children were all well. ‘They frequently congratulate me on having an English mother abroad who is constantly praying for my safety and the welfare of my family – especially when they read some of your old letters to us!’ The political outlook, he reported, ‘is not too pleasant’, but he had no wish to go into any detail, saying simply that ‘we live in hopes’, seeking solace in Samson’s biblical aphorism, ‘Out of the eater came forth meat and out of the strong came forth sweetness’.

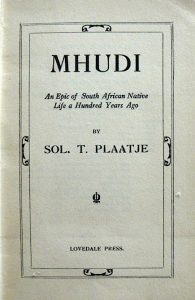

Then came his real piece of news. ‘You will both be glad to know’, he said, addressing Mrs Solomon’s daughter Daisy too, ‘that after ten years of disappointment I have at length succeeded in printing my book. Lovedale is publishing it. I am expecting the proofs any day this week.’ This was not one of his works in Setswana but Mhudi, the English-language novel he had written in London in 1920. With his next letter, he added, he hoped to be able to send her a printed copy. Mrs Solomon of course knew it well, having read the typescript and done her best to help him find a publisher for it in London. There was good news too on his Shakespeare translations: proofs of Diphosho-phosho were due from the Morija Press later in the week, while Longmans Green, the London publishers, had the manuscripts of The Merchant of Venice and Julius Caesar. ‘This simultaneous opening of printing houses in 1930 is rather strange, after they have been blocked to me with ten years of hard writing on my hands. Completing arrangements with three different houses – one after the other – made me wonder whether my days are not drawing to a close.’ In the middle of 1930, provided his health held up, Plaatje’s literary ambitions at last looked like being realised.

The Lovedale Press may not have been the international publishing house he once sought, but it was a good time to have approached them. Their decision to take on Mhudi stemmed from the arrival at Lovedale, a few years before, of a new chaplain by the name of RHW Shepherd, who had a brief ‘to assist in the publications work’. Until then, the Lovedale Press had concentrated on publishing books and pamphlets for religious and educational purposes, mostly in English and Xhosa. Shepherd, though, possessed a broader view of the literary responsibilities of a mission press, and believed that Lovedale should concern itself with providing more general reading matter for the African population. As convenor of the Publications Committee and later as director of publications, he largely decided what was to be published. Unlike his predecessors, he was quite prepared to take the risk of publishing fiction in English, one of the early beneficiaries of this new regime being the young Zulu writer RRR Dhlomo, whose novella, An African Tragedy, came out in December 1928.

Plaatje approached the Lovedale Press in November 1929. ‘A letter was submitted from Mr Plaatje concerning a MS Mhudi, a story of the Bechuanas, in English’, so it is recorded in the minutes of the Publications Committee meeting on 29 November, ‘and also concerning a proposal to publish translations of some of Shakespeare’s plays in Sechuana. Mr Chalmers [the vice principal] and the Convenor [Shepherd] were left to go into the matter with Mr Plaatje.’ Nothing came of the Shakespeare plays – unsurprisingly in view of the confused orthographic situation – but they were keen on Mhudi. At the following meeting, on 4 December, ‘Mr Chalmers and the Convenor reported that they were favourably impressed with Mr Plaatje’s MS Mhudi, and it was agreed to accept it for publication at our convenience, should the missing chapter be furnished by the author and terms satisfactory to both parties be arranged.’ By the next meeting, on 21 February 1930, agreement in principle was reached, and terms put to Plaatje. The committee accepted his suggestion that the book should be priced at 5s 6d, and a contract was drawn up, providing for a first edition of 2,000 copies, with a 10 per cent royalty payable when 700 copies of the book had been sold. Plaatje signed the contract on 19 March. Considering that overseas publishers had wanted him to contribute to the costs of publication, the terms must have appeared quite satisfactory, and the price of 5s 6d per copy – for a hard-cover book that was likely to run to over two hundred pages – not so high as to deter potential readers.

Five months later Mhudi was printed and published, Plaatje having in the meantime supplied the ‘missing chapter’ (chapter 22, ‘The exodus’). Evidence of Shepherd’s personal interest and involvement is to be found in Plaatje’s preface (dated August 1930), which concludes with an acknowledgement of Shepherd’s assistance in ‘helping to correct the proofs’. Shepherd, later in life, made it clear that he was very pleased to have been associated with the book’s publication, and often referred to it. He remembered Plaatje ‘as a man of strong and independent character, whose mind ranged widely in literature and African affairs’, and as a ‘man of much natural force’, recalling the occasion Plaatje had first walked into his office to discuss the book.

While Shepherd took a keen interest in Mhudi and its progress through production, there is nothing to suggest that he prevailed upon Plaatje to make any changes to his manuscript or that he made any himself, as some critics have argued. Since there was nothing in Mhudi that could be construed as being ‘harmful to the missionary cause’, there was no reason for him to do so. If he did have any concerns it is unlikely that the minutes of the Publications Committee would have recorded that both he and Chalmers were ‘favourably impressed’ with the MS, or that they would have agreed to publish it with no other provisos than that Plaatje should supply the missing chapter, and that terms acceptable to both parties were to be agreed.

Nor is there any textual evidence to support any charge of interference. The typescript which Plaatje supplied to Lovedale, like earlier drafts that have survived, had numerous handwritten amendments, made at various times, but they are all in his own hand; this is simply how he worked, constantly revising what he had written. Beyond a very basic mark-up by the printer there is no sign of any editing or copyediting in any other hand. One consequence, in fact, of this lack of attention to the basics of manuscript preparation was a final printed product that was riddled with errors and inconsistencies in spelling and punctuation. Nobody, moreover, carried out a proper check of chapter headings in the text against their listing on the contents page, the most basic task of any copyeditor. Six of the chapter headings do not correspond, and different numbering systems – Roman for the text, Arabic for the contents page – are used.

Further changes and corrections were made at proof stage, after the book had been typeset, but most of these were minor in nature and did not affect sense or style. The two most substantial changes were the addition of two new pages, by Plaatje, at the beginning of chapter 11, ‘A timid man’; and a new ‘Exodus’ chapter, chapter 22, only part of which had been supplied with the original typescript that Lovedale marked up for typesetting. None of this provides any reason to believe that the version of Mhudi which Lovedale published was not fully in accord with his wishes, or that there was some kind of ‘psychological war’ ‘between Plaatje and his editors’ over the text, as has also been suggested.

Michael van Reenen, Plaatje’s friend and neighbour, also helped to correct proofs. His main memory, years later, was of Shepherd pleading with Plaatje to refrain from making any further changes, being concerned about the escalating costs. There is no doubt that it was Plaatje who was making these changes at proof stage, just as he had with his typescript.

~~~

Even though Mhudi‘s publication was delayed for ten years, it was nevertheless the first book of its kind, a full-length work of fiction, to have been written by a black South African. It was this that prompted Plaatje to offer a few words in justification and explanation: ‘South African literature has hitherto been almost exclusively European, so that a foreword seems necessary to give reasons for a Native venture’, he said. ‘In all the tales of battle I have ever read, or heard of, the cause of the war is invariably ascribed to the other side. Similarly, we have been taught almost from childhood, to fear the Matabele – a fierce nation – so unreasoning in its ferocity that it will attack any individual or tribe, at sight, without the slightest provocation. Their destruction of our people, we are told, had no justification in fact or in reason; they were actuated by sheer lust for human blood.’

It turned out that this Matabele onslaught was not unreasoned or unprovoked, however. Plaatje only discovered the justification for it later in life, when he was told of ‘the day Mzilikazi’s tax collectors were killed’, and that it was ‘the slaying of Bhoya and his companions, about the year 1830’ that ‘constituted the casus belli which unleashed the war dogs and precipitated the Barolong nation headlong into the horrors described in these pages’.

These events, action and reaction, were Plaatje’s point of departure, and it is against this historical background of South Africa in the 1830s that he weaves his tale. There follows a dramatic account of the brutal destruction of Kunana, the Barolong capital, and an introduction to the two main characters, Mhudi and Ra-Thaga. Thereafter the scene shifts to the court of the victorious Matabele king, Mzilikazi. As his people celebrate their victory, Gubuza, commander of Mzilikazi’s army, utters one of the prophetic warnings that build up an atmosphere of suspense and impending doom, predicting that the Barolong would not rest until they had their revenge.

Mhudi and Ra-Thaga, meanwhile, meet one another in the wilderness, fall in love, and after several encounters with lions, meet up with a band of Korana, and join them in the hope of discovering the fate of the rest of their people. Ra-Thaga then has a narrow escape at the hands of Ton-Qon, a Korana headman who is intent on taking Mhudi as his wife, but the couple hear that the survivors of the massacre at Kunana, together with the other branches of the Barolong nation, have now gathered and made a new home in Thaba Nchu. They set out to find them, and arrive to a joyous reception from Mhudi’s cousin Baile, each amazed to find the other alive. Soon their arrival is eclipsed by that of another group of newcomers, ‘a travel-stained party’ of Boers travelling northwards from the Cape Colony, who are offered hospitality by Chief Moroka, the senior Barolong chief at Thaba Nchu. In due course, a friendship develops between Ra-Thaga and De Villiers, one of the Boer trekkers, and after much deliberation and the dispatch of a spying expedition, the Barolong and Boer leaders decide to form a military alliance and attack the Matabele.

The Matabele, for their part, prepare themselves for the onslaught. As they do so, a bright comet appears in the sky above them, an omen of defeat and destruction prophesied many times before by their witchdoctors and seers. In the battle that follows, the combined forces of Boers, Barolong and Griqua (also enlisted as allies) prove more than a match for the dispirited Matabele forces, and their triumph is joyously celebrated. In the opposite camp Gubuza brings news of the defeat of his army to the king, and advises him to ‘evacuate the city and move the nation to the north’. Only in this way, he said, mindful of an earlier prophecy, could the complete annihilation of the Matabele nation be averted.

From the tragic scene of the court of the defeated Matabele king, the action returns to Thaba Nchu, where Mhudi has been left behind while her husband is away with the army sent out against the Matabele. It is not a situation she can long endure. Having a premonition of an injury to Ra-Thaga, she decides impulsively to make her way to the allies’ camp, setting out alone on the hazardous journey. On the way there she encounters Umnandi, the former wife of Mzilikazi, forced to flee his court as a result of the machinations of her jealous rivals, and they arrive together in the allies’ camp. Mzilikazi, meanwhile, prepares to move northwards, bitterly regretting his failure to heed the warnings and prophecies that had been made: ‘I alone am to blame,’ he acknowledges, ‘notwithstanding that my magicians warned me of the looming terrors, I heeded them not. Had I only listened and moved the nation to the north, I could have transplanted my kingdom there with all my impis still intact – but mayebab’o – now I have lost all!’ Then, in one of the most powerful passages of the book, Mzilikazi makes a prophecy of his own. The Barolong, he says, will live to regret the alliance they have made with the Boers.

After so powerful and haunting a prophecy, the remaining two chapters of the book come almost as an anticlimax, and are devoted mostly to tying up loose ends in the personal relationships between the main characters. Umnandi rejoins Mzilikazi, welcomed back as his rightful queen; De Villiers, Ra-Thaga’s Boer friend, marries the girl he loves, Annetjie; while Mhudi and Ra-Thaga, after declining an invitation to stay on with their new-found friends, De Villiers and Annetjie, set off in an old wagon in the direction of Thaba Nchu: ‘from henceforth’, says Ra-Thaga to Mhudi, in the final lines of the book, ‘my ears shall be open to one call only besides the call of the Chief, namely the call of your voice – Mhudi’.

In many ways the actual sequence of events, the development of the individual characters and the interaction between them are not of crucial importance. For Plaatje did not conceive of Mhudi as a realistic novel in the Western literary tradition. He gave his book the subtitle ‘An epic of native life a hundred years ago’, seeking to dignify his tale with the sense of grandeur and significance he felt it deserved. Just as in Shakespeare, he expected his readers to suspend a sense of realism to allow for the delivery of long set-piece speeches, dialogue, songs and poems; to allow him to bring historical events backwards and forwards in time as it suited him; and to exploit for dramatic purposes an assumed historical knowledge on the part of his readers. His characters are not realistic portrayals of human behaviour but rather vehicles for the expression of a variety of human qualities and ideas which he wished to explore.

Mhudi was the outcome of a quite conscious and deliberate attempt on Plaatje’s part to marry together two different cultural traditions: African oral forms and traditions, particularly those of the Barolong, on the one hand, and the written traditions and forms of the English language and literature, on the other. As noted in chapter 10, when he set about writing Mhudi in 1920 he looked to the imperial romance for inspiration and for a literary model, drawing in particular upon Rider Haggard’s Nada the Lily. A further advantage of Nada, as Plaatje saw it, was that it showed how it was possible to explore and to incorporate oral traditions (Zulu), using them as the backdrop to the imagined tale of Umslopogaas and the beautiful Nada.

While Rider Haggard was able to go to published sources for his oral traditions, Plaatje got most of his at first hand. The slaying of Bhoya and his companions, for example, was unrecorded in any published histories, and Plaatje only heard about it ‘from old people’, ‘by the merest accident’, ‘while collecting stray scraps of tribal history, later in life’. Other stories came from members of his own family. His use of proverbs and other idioms was likewise a quite deliberate attempt to convey something of the richness of the cultural resources upon which he was drawing. Often his technique of literal translation was strikingly successful. ‘I would rather be a Bushman and eat scorpions than that Matabele could be hunted and killed as freely as rockrabbits’, says Dambuza, one of Mzilikazi’s warriors, at the Matabele court. Later he observes: ‘Gubuza, my chief, your speech was the one fly in the milk. Your unworthy words stung like needles in my ears.’

Plaatje was struck by the way Tswana oral tradition and the written traditions of English literature shared a common fund of literary and cultural symbols. In Mhudi he set out to explore this idea, not least in relation to omen and prophecy, and their association with planetary movements – preoccupations of both Shakespeare and the traditions of his own people. This had always fascinated him. ‘In common with other Bantu tribes’, he had written in his newspaper at the time of the reappearance of Halley’s Comet in 1910, ‘the Bechuana attach many ominous traditions to stellar movements and cometary visitations in particular’, and he had added: ‘space will not permit of one going as far back as the 30s and 50s to record momentous events, in Sechuana history, which occurred synchronically with the movements of heavenly bodies’. Ten years later Plaatje found both the time and space to do exactly that in writing Mhudi, even if he had then to wait a further ten years before the results were published.

This awareness of the literary possibilities that lay in the manipulation of symbols that had meaning in both Tswana and English cultures also found expression in the humorous lion stories that appear in the early part of the book. These serve as a means of testing the courage of Mhudi and Ra-Thaga, and are contrasted later on with the cowardly reaction of Lepane, a traveller faced with a similar challenge. That lion stories of this kind were a familiar motif in Tswana tradition emerges from the story that Plaatje himself reproduced in his Sechuana Reader. Like the lion story that appears in chapter 6 of Mhudi, its central point is the way in which the protagonist proves his bravery by holding onto the lion’s tail. At the same time, lion stories of this kind, serving a similar function of demonstrating bravery and cowardice, appear in English literature too – in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour Lost, Julius Caesar and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, all of which would have been very familiar to him.

Another lion story came from Plaatje’s own family history, albeit suitably reworked for his own dramatic purposes. ‘I have had some exciting times in my young life’, Mhudi tells Ra-Thaga in the middle of chapter 7, informing him that ‘the day I met you was not the first occasion on which I had a narrow escape from a roaring lion’. She then tells him of the time she came face to face with a lion, stood her ground and emerged uninjured after her companions managed to frighten it off by shouting and waving their peltries (fur skins) at it. The story had come down to Plaatje from his great-grandmother: she had been the girl who, in the early 1820s, had faced down the lion in a bush near the Kunana Hills, just where the episode in Mhudi takes place.

In 1916, as we have seen, Plaatje had expressed the view that he thought it likely that some of the stories on which Shakespeare’s dramas were based ‘find equivalents in African folk-lore’. When he looked into this question more closely he found this prediction to be correct. The lion stories, and his exploration of the symbolism and meaning of planetary omens and prophecies, were two of the outcomes. This was the kind of cultural borderland he loved to explore.

~~~

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media Mhudi Sol Plaatje Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876–1932