Filling in the missing years of naturalist William Burchell’s southern African Journey

More about the book!

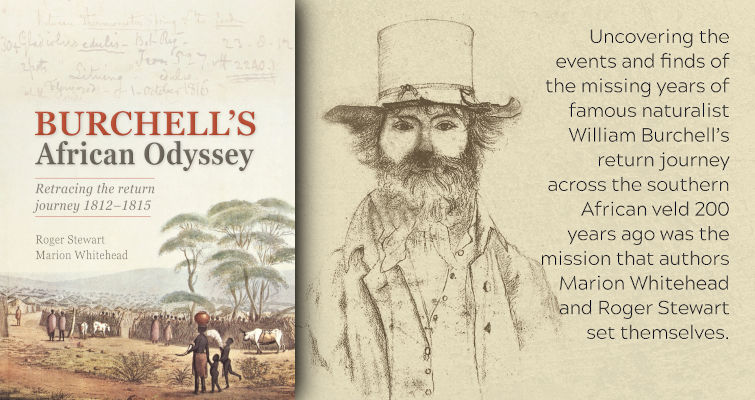

Uncovering the events and finds of the missing years of famous naturalist William Burchell’s return journey across the southern African veld 200 years ago was the mission authors Roger Stewart and Marion Whitehead set themselves in Burchell’s African Odyssey: Revealing the Return Journey 1812–1815.

‘Burchell’s work was so thorough that it is still consulted by scientists today.’

Suffering a mechanical breakdown in a remote part of the Karoo while travelling off-road is a disaster any adventurer would dread. But if you’re in an oxwagon pioneering a new route through unknown territory and your disselboom, the main haulage shaft of the wagon, breaks while crossing a dry donga, you plainly have a crisis on your hands.

This was one of the many challenging situations faced by the famous explorer and naturalist, William John Burchell, on the return leg of his four-year, 7,000-kilometre journey across the southern African veld more than two centuries ago. Along the way, the idealistic young Englishman collected more than 63,000 specimens of plants, mammals, birds, insects and snakes, describing many of them for the first time for science. By the end of his great trek, he had matured into an early systems thinker and ecologist – long before the term was invented.

The two volumes of the fascinating book he wrote about his adventure, Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, cover only the first third of his remarkable journey, from Cape Town to Litakun, the capital of the Bachapin tribe living on the southern edge of the Kalahari. His return trip, via the Karoo, the turbulent eastern frontier and along the Eden-like southern Cape coastal plateau, from 1812 to 1815, remained a mystery. However, this was when he collected the vast majority of his specimens and made many important discoveries. For instance, he realised the black and white rhino were two different species, and that the mountain zebra was different from the plains zebra – now known as Burchell’s zebra.

Recognition of his contribution to science has been immortalised in the names of many species: Burchellia bubalina (the wild pomegranate), Protea burchellii (Burchell’s sugarbush) and Podalyria burchellii (hairy Cape sweetpea) are among the more than 250,000 hits a Google search brings up.

We set out to probe the tantalising enigma of the return journey of this very talented, multi-skilled explorer. We studied the map he drew, combed letters in archives and contacted descendants of Burchell’s brother, who emigrated to South Africa. Unfortunately, there is only one surviving journal covering just one month of his return journey. But his notebooks and specimens have been preserved in the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and many of his drawings are at Museum Africa in Johannesburg. They provided clues to his adventures and mishaps on the return journey.

The resourceful Burchell repaired his broken disselboom with the help of his Khoekhoe crew and possibly some local San tribesmen that he befriended. Before moving on towards Graaff-Reinet, he collected a fine specimen of a poison onion (Dipcadi glaucum), that was later featured in a British horticultural magazine.

In the Karoo and the Eastern Cape, he found more beautiful bulbs that he took back to England where he successfully cultivated them and introduced them to the horticultural trade. Keen gardeners still treasure the Orange River lily (Crinum bulbispermum), crown lily (Ammocharis coranica), candelabra flower (Brunsvigia radulosa), and white paintbrush lily (Haemanthus albiflos).

Travelling along the eastern border of the Cape Colony just a year after the fourth frontier war, he trekked from one military post to the next to reach the mouth of the Fish River, a point vital in helping him compile a map of southern Africa that remained the best available for much of the nineteenth century.

Soon after collecting the first clivia near what became the 1820 settler village of Bathurst, he narrowly avoided another disaster. While attempting to cross the estuary of the Kowie River at today’s Port Alfred, his overladen wagon got stuck in the soft sand on a rising tide.

Burchell backtracked to the Blaauwkranz military post and took a back route that crossed the Kowie some 20 kilometres upstream. However, benighted on a difficult section with his overloaded wagons, he experienced a fresh disaster. Two teams of his oxen were stolen by a Xhosa raiding party and he was left stranded at the campsite he wryly named Robbers Station.

In the southern Cape, he was in botanical heaven, exploring the forest and fynbos-clad mountains of the Outeniqua and Langeberg Mountains, along what is today known as the Garden Route. The spot where he camped at George is now part of the Garden Route Botanical Garden, and the only known bust of him has been erected there to commemorate his remarkable contributions to natural history in southern Africa. His work was so thorough that it is still consulted by scientists today.

Sadly, Burchell did not receive the recognition that he should have in his lifetime. We hope that revealing the missing story of his four-year return journey helps throw new light on the contributions of a remarkable man and stimulates more interest in this neglected hero of British exploration and science.

Burchell’s African Odyssey: Revealing the Return Journey is out now.

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

About the book

The English naturalist William Burchell arrived in Cape Town in June 1811 to explore the flora and fauna of the vast southern African interior. Over a four-year period, and travelling in a custom-built ox wagon, he amassed an astonishing 63,000 specimens of plants, bulbs, insects, reptiles and mammals – many not previously documented for science – as well as over 500 paintings and illustrations.

While the outbound trek is well described in Burchell’s famous travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, little has been published about the challenges and discoveries made on his return journey to Cape Town, from 1812–1815. This pioneering book traces the homeward leg of Burchell’s epic odyssey – through the arid northern Cape, the Great Karoo, the war-ravaged eastern Cape, and along the Eden-like southern Cape coast.

Drawing on primary and secondary sources, including Burchell’s letters and the detailed map he created to record his trek, the authors have crafted a thought-provoking and beautifully illustrated account that encompasses both the genius of the man and the natural history of the region that so intrigued him.

Categories Non-fiction South Africa

Tags Burchell's African Odyssey Marion Whitehead Nature Penguin Random House SA Roger Stewart The Penguin Post