Crisp Packets and Stolen Keys, Bottlecaps and Broken Glass – Stuart MacBride on writing

More about the book!

Why go through the wringer if you aren’t going to put it in a book? Stuart MacBride writes about how an idea he’d sat with for 13 years finally found legs in the dark humour of the Scottish weather system.

‘One of the things I enjoy the most about being a writer is setting up situations like these then figuring out exactly what that shove looks like, who gives it, and how bad things will get as it all comes crashing down. With the usual answer being: very.’

For some strange reason, the nice people at Penguin Post think you’ll be interested in reading about how I tackle writing a book, which seems a bit weird to me, but who am I to judge? So grab a cuppa and I’ll try to make the months-long slog of sitting on my bottom, in front of the computer, drinking lots of tea and making stuff up seem a bit more exciting than it really is.

I’d love to be able to point to a single point of inspiration when I’m asked where a book came from, but the truth is that I’m a magpie (albeit a large, hairy, somewhat-tubbier-after-lockdown [though still uncannily sexy], Scottish one). All my novels are nests constructed from crisp packets and stolen keys, bottlecaps and broken glass.

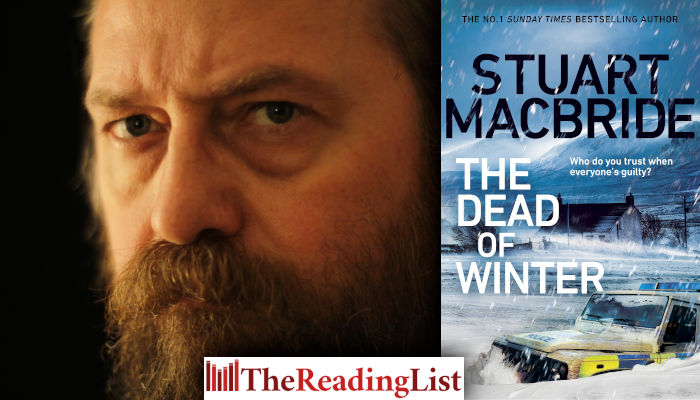

The Dead of Winter (the book I’ve been instructed to shamelessly plug here) is no exception.

Way back in 2009 I was doing research for my sixth book, Dark Blood, talking to police officers about how they manage sex offenders who’ve served their time and been freed from prison. They’re not just turfed out the prison’s front door with a cheery wave and a polite reminder to behave themselves – they’re released on licence and subject to control orders, monitoring, and regular evaluations. Which is where the Offender Management Unit come in. And talking to these officers, I was shocked by just how many people they each had to deal with. Their caseload is huge, and while some offenders only require the occasional visit to make sure they’re complying with their release conditions, others need to be seen every single day. Questionnaires must be completed, forms filled in, reports written, judgements taken about safety, and then the cycle starts again. On and on and on and on …

And if you get it wrong, just once, horrible things happen.

It sounded like a lot of hard, soul-destroying work, but it got me wondering if there was another way to go about it. What if you could take the worst offenders from all over Scotland – the ones who needed the closest supervision, who posed the biggest threat to society – and put them in one place? A little village all of their own. Somewhere they could live a reasonably normal life with no risk to, or from, the general public. Because although there would be lots of rules and regulations, surely it’s better to live in what’s essentially a comfy open prison than have to face angry mobs every time the red-top tabloids found out where you live.

I liked the sound of that. It was an idea with ‘legs’.

But that wasn’t the book I was writing at the time, so the setup was duly scribbled on a Post-it note and ceremoniously added to Stuart’s Great Big Whiteboard Of Doom!™ where it languished for the next 13 years.

Let’s call that the ‘stolen keys’.

The ‘broken glass’ arrived during the winter of 2020/2021, which might not have been too bad in beautiful South Africa, but up here in the northeast of Scotland it was bloody horrible. The worst winter in over a decade, with chest-high drifts of snow, blizzards that didn’t seem to stop for weeks, howling winds, and freezing temperatures (on one delightful night it hit minus eighteen). That on its own would have been bad enough, but about two days into The Winter From Hell, my wife, Fiona, went ‘off the legs’, as we say at Casa MacBride, with two slipped disks, leaving me to look after the cats, hens, and horses all on my own. Now, Stuart does not like horses. Horses worry and alarm Stuart. They’re too big and they stand on people and bite them and squish them and … do lots of other sinister stuff. And the buggers are a hell of a lot of work, most of which involves moving Very Heavy Things – like dragging tonne-sized builder’s bags of hay out through the snow and into the field twice a day. Then doing the same with sixty litres of water. In screaming blizzardy horrible conditions. With lots and lots and lots of swearing.

And, if that wasn’t enough: the heating oil ran out, because the oil company had left it too late to top us up. And now we were snowed in, so they couldn’t get to us. And we were running out of food. And there was a pandemic on. And it was cold, and difficult, and exhausting, and a thoroughly miserable experience. And there was no way I was letting all that suffering and effort go to waste – it was going in a book.

But I still needed my bottlecaps and crisp packets.

The former popped out of the aether one lunchtime, while I was noodling about the kitchen, making fancy-pants ramen, singing away to myself (this is something I do quite often: making up strange, silly little songs to entertain Fiona). There was a programme on the radio about Queen Victoria’s vast bloomers being sold at auction for an obscene amount of money. Which inspired me to go warbling off into Victoria finding euphoria and phantasmagoria in the Waldorf Astoria and the Mines of Moria. I know it’s not pretty, but that’s how my mind works.

My mind then decided that Victoria would make an excellent brand-new character for a book. Only instead of being a large queenly person, she’d be a big, strong, strapping farmer’s lass, with the nickname ‘Bigtoria’. Bigtoria would be a really strict (and kinda scary) detective inspector, and she’d have a sidekick (as every detective inspector must), but this sidekick wouldn’t know anything about her (because he’s new), and he’d be called Edward (a nice normal name for a nice normal person).

We all know that fictional detectives without a fictional crime to solve aren’t worth the Post-it notes they’re scribbled on, so they needed something to investigate. But I had no idea what …

Finally, it was time for those shiny, shiny crisp packets.

I have a recurring theme in my work involving really nasty old people. No idea why, and I don’t do it in every book, but it’s something that’s featured in several of them. It might have something to do with the fact that in a lot of fiction, old people are portrayed as doddery benevolent types who bake cakes whilst dispensing endless cups of tea, Werther’s Originals, and dollops of sagely wisdom. Or they’re victims to be buried. Or a nuisance to be ignored. But I always wonder: what do writers think happens to really nasty young people? Do they hit their late sixties and get issued with false teeth, a bus pass, and suddenly become nice? That with knitting comes kindness? That cardigans breed compassion? No: horrible people remain horrible, they just get more wrinkly.

That gave me Marky Bishop – a gangster of the worst kind, who’s spent the last twenty-five years in prison for killing someone, then cutting their body into bits with a circular saw. But he’s eighty-two now and dying of lung cancer, so they’ve given him compassionate release. Trouble is, because of his gangland past and the fact that someone might well want revenge for their dismembered ex-colleague, the authorities couldn’t just chuck Mr Bishop out of prison and hope for the best. They’d need somewhere safe to put him.

Cue a swift visit to Stuart’s Great Big Whiteboard Of Doom!™ and a hunt through the Sticky Post-it Library Of Ideas That Might Come In Handy One Day, because I was sure I’d added something to the collection thirteen-odd years ago that might help. And there it was: a town for criminals.

It didn’t take long to weave my shiny objects together with twigs and feathers and bits of dead grass into Glenfarach – a sleepy little snow-dusted village, nestled deep in the Cairngorms, populated with murderers and thugs and sex offenders, all doing their best to rub along together, keep their noses clean, and not get thrown out into the big bad world, as the worst winter in a decade comes sweeping down the glen, ready to smother everyone.

Seemed logical to me that somewhere like Glenfarach could only maintain its equilibrium if everyone played by the rules, but of course we live in a world where governments are obsessed with cutting expenditure. It might be easy to manage 200 offenders if you’ve got twenty or thirty police officers on site, a good surveillance system, and a full social work team, but it’ll be a lot more challenging when the budget’s slashed, vital equipment’s not being repaired or replaced, and only four officers remain. Then that equilibrium becomes extremely wobbly, liable to collapse if someone gives it a shove in just the wrong direction.

One of the things I enjoy the most about being a writer is setting up situations like these then figuring out exactly what that shove looks like, who gives it, and how bad things will get as it all comes crashing down. With the usual answer being: very.

Of course, once the nest is made, you’ve still got to turn it into a book.

I’ve developed a habit over the last seven years of doing my first drafts as screenplays – and I know that sounds all, ‘Take me, Hollywood, you gorgeous beast!’ but it’s a very immediate way to build the book – focusing on the action and the dialogue. Then, once I’ve finalised that with my editor, I go back to the start and adapt it into a full-blown, big-boy-pants-wearing novel, concentrating on giving you, the lovely reader, an experience that’s as close to the main character’s as I possibly can. Doing my best to get you seeing the sights, hearing the sounds, and smelling the smells. And, for this book, feeling the overbearing weight and cold and horribleness of having to do everything in a howling blizzard.

Only with fewer horses.

The Dead of Winter is out now.

~~~

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

Categories Fiction International

Tags Penguin Random House SA Stuart MacBride The Dead of Winter The Penguin Post