‘Achen’ means Twin, or the eldest of twins. ‘But where is the other one?’ people ask. – Read an excerpt from An Image in a Mirror by Ijangolet S Ogwang

More about the book!

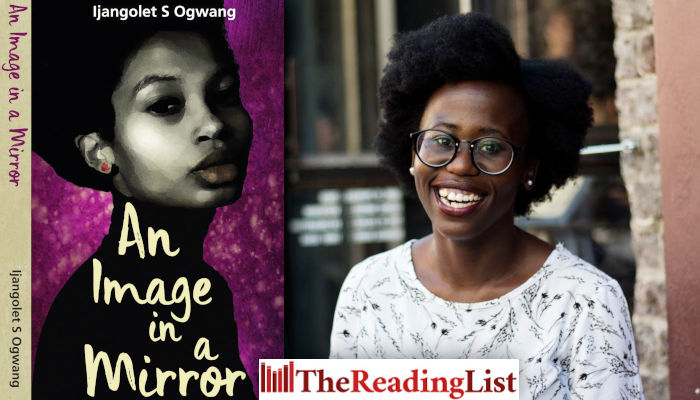

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from An Image in a Mirror, the debut novel from Ijangolet S Ogwang.

Achen and Nyakale: twin sisters, separated from childhood to inherit different destinies.

In the hope of inheriting a better life, a mother makes the heart-wrenching decision to send one child, Nyakale, to South Africa to be raised by her well-off sister, the child’s aunt, who has no children of her own. The other child, Achen, stays in Uganda to be raised by their mother in a village.

An Image in a Mirror is a richly told and deeply intimate African story about the coming of age of two young women, who are the same as much as they are different. When the sisters, at the age of twenty-two, finally cross their respective worlds to meet, how mirrored will each feel about the other?

Heralding a new female voice in fiction, An Image in a Mirror is a profound debut novel.

About the author

Ijangolet S Ogwang was born in Kenya to Ugandan parents and raised in South Africa, more specifically in a small town in the Eastern Cape called Butterworth. She is most passionate about women empowerment and the development of Africa. She co-founded Good-Hair and works as an analyst for Edge Growth, a company focused on growing small businesses in South Africa. Between this and ‘adulting’ she makes up stories.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

Achen

‘Achen’ means Twin, or the eldest of twins. My whole life, it’s been a tremendously hard thing to explain why I carry that name.

‘But where is the other one?’ people ask.

I wonder why Mama even gave me this name, when she knew that Nyakale was meant to go to Aunt Mercy.

Throughout my schooling, the older I became, the more plausible it became to say that my twin had died at birth, or sometimes that she’d drowned when we were younger. On occasion I’d go so far as to include myself in the story as the hero who tried to save her – but the doctors at the Nyako clinic refused to attend to her swiftly, and she died in my arms.

I used to feel guilty about the stories I made up. Over time, the guilt transformed into entitlement: it’s my right to tell her out of my life as I desire.

My feelings have always been anger mixed with resentment. I’ve lived hearing my mother shed tears for Nyakale, her words replaced by weeping and supplication. I wonder if one day Mama will finally free herself from this self-imposed life sentence of anguish. When I was younger, Mama wept rivers often; these days, her tears only visit occasionally.

I wonder if Nyakale knows that she left with a piece of Mama, a piece that will always be lost to me. In the village, you hear things that are not meant for a child’s ears. Like someone saying that Aunt Mercy was barren – ‘Able to accumulate wealth, but not to give birth to a child. What a shame.’ I often wonder what the real reason was for Nyakale being dispatched to South Africa. If it was really the war and poverty here, or if it was the riches and power that Aunt Mercy held over her older sister – the same way the politicians stand high and mighty, triumphant over those who they’re meant to serve. It’s troubling, how people here treat the wealthy as more human than the rest of us.

Over the years, Aunt Mercy has come to visit us once or twice, although she’s never brought my sister with her. I always hate it when Ugandan–South Africans come to the village, retelling their stories of a Uganda that no longer exists except in their memories. Their children are better because they don’t pretend to conjure up this exaggerated interest.

Whenever parcels arrive from South Africa, Mama’s ‘Thank you, ah we thank you!’ is too enthusiastic – as if she worries that the simple words are insufficient to communicate the extent of her gratitude. All aimed at guaranteeing that our aunt’s ‘undeserved’ goodness does not cease.

Me, I think these parcels are the bare minimum she can do.

The mirror is shattered into pieces on the floor, next to the stool where Mama’s hair-oil bottles are arranged, from tallest to shortest. I will tell Mama that I found it lying there. I know that since the mirror is from Nyakale or Aunt Mercy, it is dearer to Mama than most things in this house. In every room of the house lies a symbol of the upbringing of a Nyakale who was never actually here, but who we dare not forget.

This mirror is among the many gifts that have flowed from the Land of Milk and Honey. I was always taken aback by how simple it was – small, round, plain, not even full-length. They certainly could have sent something more desirable. A simple thing for simple people, Aunt Mercy must have thought.

I’ve tried to find reasons to excuse her for not sending a more remarkable mirror. Perhaps the stories we heard about South Africa, how it’s miles ahead of Uganda, were fables, like the ones we’d entertain each other with as kids?

‘Mama, what’s the matter?’ I cautiously pull back the kitenge, already hearing her weeping as I approach from the living area. I ask this question out of habit. I know it’s this day that’s bittersweet.

‘It’s nothing, Achen,’ she says, abruptly wiping her tears and resuming the role expected of her: sweeping on bent knees.

Today is our, I mean my, twenty-second birthday. This is one of the hardest days of the year; a time of celebration and sorrow for Mama.

‘Did she not choose to send the other one to South Africa?’ the village voices murmur. ‘Then why is she still so downcast?’

‘Ah, it’s been several years, sister, we must accept that things work out for the best.’

‘You wipe those tears.’

With the years, what’s helped is that the gossip and questions have subsided, leaving Mama’s mourning to become a private thing, with no jury to declare it invalid.

‘I’m sorry, Mama, I wish things were different.’ We always speak about Nyakale in this cryptic manner.

‘I know, my daughter,’ Mama solemnly responds, rising and busying herself elsewhere.

Every year, Mama insists that we have a birthday meal with the people in the village, to thank God for my life. My friends Cynthia and Sandra are coming to help with the preparations. They’re both visiting home: Cynthia’s just completed uni in South Africa, and Sandra recently got back from the UK, where she’s been studying. I’m feeling nervous for some reason about seeing them later. I’m hoping that in the evening the girls and I will get to go to the village centre and celebrate with some Nile Specials. The centre is where we all gather once the sun has set and the day’s lifting from our bodies. We sit on upturned crates as people play draughts and pass around sodas. Televisions blare with different European soccer matches, over arguments about whether Chelsea or Manchester United will win the Champions League.

I love it here, in this place I call home. Memories would never keep me warm in a foreign land. Having been the one who stayed after our O-levels has never bothered me; besides, Mama couldn’t afford to send me to Makerere University, let alone out of the country. Most scholarships are reserved for children whose parents are in public service. Had I decided to leave, I would’ve had an entirely different life – and the lives of the women in the Women’s Land Rights Cooperative would have been different too.

But Sandra and Cynthia were always enchanted with the idea of leaving. Thinking only of the good things it could bring, and not the ways leaving would change and harden them if they weren’t careful. What people never consider is the fact that the city isn’t unendingly spacious, with room for everyone’s dreams; from the stories I’ve heard, sometimes it’s the altar upon which dreams are killed.

In any case, I’m excited about the work I’ve been doing here with the Cooperative – it could really make a meaningful change. We’re starting to make ground, but the very people we’re asking to amend the customary laws that bar women owning land are the ones who are snatching it, left, right and centre.

I vividly remember the first time I witnessed this – a thing I could not make sense of for the longest time. Aunty Anna, Nafula’s mother, being violently dragged out of her married home by relatives of Papa Oride. The female relatives watching as though it wasn’t a problem. I specifically remember the man with a plump round face, a scar under eyes that were too large for his face. He kept on shouting, ‘No woman can own land that belongs to a tribe she no longer belongs to. My brother is dead, so she must go back home to her people!’ A vicious look on his face. The year was 2004; I’d just turned ten.

Aunty Anna attempted to protest, but was evidently overpowered both by the people removing her and by Mama telling her, ‘Let’s just go, Inachi.’ The two walked arm in arm to our compound, which wasn’t too far from Aunty Anna’s home. Aunty looking like her feet would collapse under her if not for Mama holding her up. She was weeping, repeatedly shouting, ‘Oh God!’

I’ve never been one to question the way things are done in the village. When the women go on their short pilgrimage to the river – that experience houses some of my fondest memories. It’s more than a walk; it’s an entire learning experience. Or the first time Mama taught me how to mix ugali: once the water’s boiling hot, you need to add the millet flour, rapidly mixing it with the water with an even motion. If you don’t get it right, you end up with lumps of uncooked millet. I struggled with numerous trials but finally I got it right, and the whole family was excited to be eating food I’d cooked. The satisfaction on their faces marked the day as great.

I remember being five, with a towel on my head, trying to balance a jerry-can of water the way Mama does. I walked as slow as I could, one foot in front of the other, holding my breath – but the jerry-can had no respect for my juvenile efforts and so it fell. One day I, too, would be able to walk gracefully with the jerry-can perfectly sitting on my head, under my spell. I would never have thought that the beauty of being a woman, these gender roles they speak of, would one day become something I detest. It is a beautiful thing, but also a hard thing, to be a woman here. Yes, you can have a voice, but at times you’ll be expected to hide that voice in a box and not let it out.

The greatest challenge, if you want to be of value in the village, is to be a girl child. A lot of the elders, especially the men, still look at me and see a little girl with big eyes. Papa Nkura remarks, ‘A woman’s place is tending the pots and not trying to tell us how we ought to farm these fields. This child of yesterday, what does this young girl know that us old people don’t know, when she’s only been on this earth for what, twenty-two years?’

To which, as expected, I dare not respond. Instead, I humbly bend my head ever so slightly, pressing my lips together lest a disrespectful word escape. Mama would be ashamed and scold me sorely if I said anything. This is primarily why I choose to remain silent. I know it’s important to her what the people in the village think of her, that they see I was raised right. Right – I’ve always wondered what this means, and who defines it.

I used to be envious of Yokolam. The village was more forgiving of him and his pals as they forged their hopes and dreams for our people. The young men sat with the elders, fully engaging in the affairs of the village, sharing opinions on the elections and the absurdities of government officials. Yokolam always enjoyed being important, being called upon by the elders. He truly must have had some hidden grey hairs, for all the wisdom in his head. He was the love of my life, the bravest and most industrious of the boys in this village.

I can’t really explain when and what happened, how we got here. We were like two reeds in the Nyaguo Lake, one of the most beautiful lakes in the world, where the waters shimmer in the sunlight, the perfect shade of blue. Not too dark or too light. We grew besides each other, and as time passed our stems slanted towards one another. We were always convinced that ours would be a love story, a story about falling and continuously falling.

But Yokolam was a dreamer; the village was always too small a place for him. This is where we disagreed: he wanted to go away from here and I wanted to stay. How does love live past this? I do not know yet. There are memories we all want to run away from, but he was always more haunted than most. There are days I seek to understand this, and others where I try but can’t. I worry that I’ve lost him to the city. I’ve seen what the city does to people. It can cause you to hate the very food that you were raised on and made you strong; to roll your eyes at the person who carried you on her back before you could walk. You swiftly learn to look down on those who are, in fact, much taller than you.

In the village, I’ve grown to see humans as half whole, half forming. It’s our choices that inform whether good prevails or evil swallows us. I hold these same ideas about this home of mine, Uganda: surely the presence of evil only acts as a backdrop to the good that must exist.

I learnt this lesson early in life. It’s in the sun and how it keeps us warm – but equally, it’s in how, when I was eleven, Mama and the whole village prayed to God for rain, as it had not rained for six whole months. The storerooms of vegetables and grains ran low and the cattle were beginning to die. The sun eventually had mercy and gave way to the rain. The village gave sacrifices of thanks and everything was as it should be.

It’s in the Nile – the source of water for our livelihoods, but also what consumed Lutalo, Aisu and Samuel whole at the tender age of ten. That day is tattooed in my memory.

We were all crossing the river, the wooden bridge squeaking as we put one tiny foot in front of the other. We paid it no mind. After all, we’d crossed this river too many times to count. We were laughing and lying to each other, as kids do, with the boys behind us telling us how they’d be warriors one day.

Then I heard a crack, and screams. It seemed there was no time between the two sounds. I looked behind me and there in the river, holding onto a broken section of the bridge, were Lutalo, Aisu and Samuel. I looked in their eyes and saw terror, nothing that looked like them. Their heads disappeared into the water, reappearing briefly, the planks disintegrating. They fell silent, and we stood helplessly listening to the waters. And then they were gone, and we finally returned to our bodies.

We ran all the way home, but the ‘big people’ said it was too late – in that season, that river was a killer in minutes. Life is like this: a constant oscillation between good and bad, hope and despair.

Cynthia and Sandra have arrived. I can hear them outside, already arguing about something. Their one commonality the shared belief that nothing remarkable happens here. Sandra is cynical and generally distrustful of people, whereas Cynthia tends to make room for idealism.

‘Change will never come, banange! Just look at these politicians and their disregard for the country, blatant in their corruption as you the people starve. I’ve been away for three years now but everything is the same as I left it!’ Sandra says, snapping the gum in her mouth.

Sandra’s family is political, with family members occupying seats in parliament and serving as ambassadors. Her closeness to politics has made her jaded – what she calls ‘seeing things for what they are.’

‘It’s people like you, Sandra, that are the problem,’ says Cynthia, ‘constantly distancing yourselves from the people and giving in to this persistent cynicism.’

‘Ah, Cynthia, come on, let’s be real. Our mothers are still waiting patiently for a change that will never come. This is why we both left in the first place.’

One more iteration of a conversation had many times over. A conversation between two people who in different ways desire things to be made right. I silently listen to them, thinking about how after all these years they both have but also haven’t changed. I have missed them – even this constant bickering.

Just as I thought I’d dodged a bullet, Cynthia begins: ‘What I’d like to know from Achen is why she insists on suffering‘ – the word exaggerated and heavy on her tongue.

This sends Sandra into waves of laughter. The moment would be incomplete without this mockery.

‘I’ve explained myself multiple times, Cynthia. It isn’t all bad. There’s a lot of injustice to make right here, but it’s also home. I really think there’s a lot I can change with the Cooperative. If we don’t do this work who will save us? No one! The suffering you talk of will persist.’

‘Ah, Ache, you and these ideas of ‘evil prevails when good men are silent’. We’ve all heard of good men killed without a second thought, just for thinking they can be righteous advocates of progress. Goodness prevailing? It doesn’t happen here.’

I owe my being to this soil. I remember reading this phrase in a book in secondary school, and it’s been engraved in my mind ever since. How do I begin to leave the land that’s home to all my memories, and the things I dream of changing are all here?

‘Ah, Ache! This is why we’ve always told you these brains of yours could be put to better use elsewhere. Here, that idealism will soon give way to reality.’

I know not to challenge Cynthia, lest we talk ourselves in circles the whole afternoon.

As the people begin to gather in the compound, my mind drifts to thoughts of Nyakale. I secretly hoped that today she would perhaps send a sign, a letter, anything – but still nothing. I resent her silence, and those thoughtless gifts – small cards containing money and the words ‘From Inachi and Nyakale’ – which I knew Aunt Mercy had written. And I just couldn’t bear looking at that mirror any more.

Hate is a strong word, but it makes my situation more bearable.

Categories Africa Fiction South Africa

Tags An Image in a Mirror BlackBird Books Book excerpts Book extracts Ijangolet S Ogwang Jacana Media