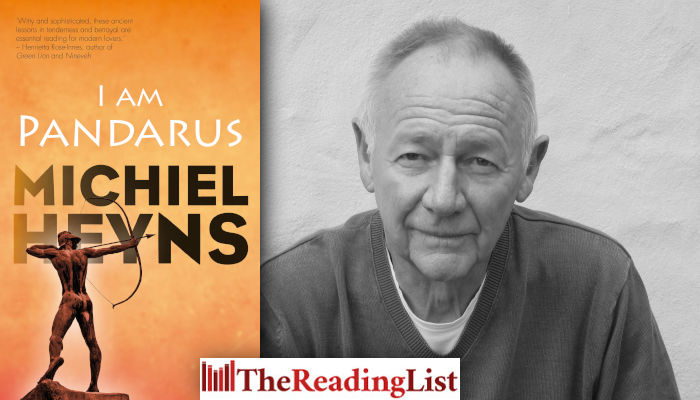

Read an excerpt from I am Pandarus, the new novel from award-winning author Michiel Heyns

More about the book!

Jonathan Ball Publishers has shared an excerpt from I am Pandarus, the new novel from acclaimed author Michiel Heyns.

I am Pandarus has been shortlisted for the Herman Charles Bosman Prize for English Fiction at the 2018 Media24 Books Awards.

Heyns is the author of seven previous novels, and the winner of the Sunday Times Fiction Prize and the Herman Charles Bosman Prize for English Fiction.

I am Pandarus is a retelling, from a modern perspective, of the story of Troilus and Criseyde, as previously told by Chaucer and Shakespeare. The narrator in Michiel Heyns’s lively iteration is the go-between, Pandarus. But the novel opens in a gay bar in present-day London when an editor at a publishing house, recently abandoned by his lover, is accosted by a charismatic stranger.

The stranger turns out to be the modern avatar of Pandarus, intent on getting his version of events published; countering the unflattering portrait of him that Shakespeare has given to the world.

The main body of the novel is Pandarus’ retelling of the story of Troilus and Criseyde from his own very particular point of view.

This central narrative is interspersed with periodic meetings of the editor with Pandarus, as the latter supplies instalments of his tale. The result is an urbane and sparkling rendition of a classical tale, in a style which old and new fans of award-winning Michiel Heyns will love.

Click on the link above for more about the book!

Read an excerpt from the novel, in which Pandarus introduces his tale:

The first principle of rhetoric, we are told, is that the teller of a sad tale must show a sad face: don’t be caught smiling at the misadventures of your characters, lest your listeners doubt your good

faith, or, more disastrously, the seriousness of your tale. Clowns are a penny a dozen; tragedians are a rare and distinguished breed.

So bear with me while I compose my countenance and commence the grievous history of Troilus and Criseyde – and there’s no point in pretending that there is any possibility of a happy ending.

This is not that kind of story, the newfangled kind that keeps you guessing before rewarding you or disappointing you at the whim of the author. This is a story dealing with recorded history or at any rate legend; and it is a matter of public or literary record that Criseyde betrayed Troilus in the end – not to mention, depending on what one takes the end to be, the little matter of the sack of Troy by the Greeks. There are no surprises in this story: the wheel of Fortune has never been known to reverse its direction.

My matter, then, is the story of Troilus and Criseyde – including, I might add in all modesty, my own part in their history. You’ll know, of course, the basics of the story: the siege of Troy is probably the best-documented military action in history or legend, as is its ostensible cause, the extremely unwise abduction of Helen by Paris – as good an instance as any in history of the catastrophic consequences of irresponsibility in high places. Had Helen been a milkmaid, Menelaus a small farmer, and Paris really the shepherd he was pretending to be, we’d have had some spilt milk, hurt pride and a broken nose or two; but, Paris being the spoilt son of the king of Troy, and the favourite of Aphrodite herself, what we got was the sacking of a city, and a slew of epic, tragic and even comic literature.

My story starts, then … well, it starts with the abduction of Helen, and that story starts, of course, with a squabble amongst three goddesses, and an unwise judgement by a young prince, but all that is too long a tale, besides being sufficiently well known; my story starts with a prophet named Calchas – a bit of an operator, really, and not much liked in Troy, but respected for his undoubted powers of divination. He seemed to have the ear of Apollo of Delphi, because Calchas had, more often than mere luck could have contrived, foretold events with uncanny accuracy – usually unpleasant events, it must be added, but that might not have been his fault; we know that the messenger is not to be maligned for the message. I am trying to be charitable to the man, because he married my eldest sister; but she died in childbirth when I was only about six years old, so I hardly knew her, and I rather lost touch with him after her death. In time I did get to know his daughter, my niece, about whom later.

In any case, this Calchas, through his special influence with Apollo, was tipped off, some nine years into the siege, that Troy was going to be put to the sword. His way of profiting by this privileged

information was to sneak off in the night to curry favour with the Greeks. They, liking what he told them, set him up as their resident soothsayer, and were generally careful to give him the kind of treatment he seemed to think he, as a prophet of Apollo, was entitled to – even the Greeks being susceptible to the common failing of taking people at their own estimate.

In Troy, of course, his desertion was seen as an act of treason, though the more cool-headed amongst us recognised it also as an unpropitious omen – I mean, if the soothsayers start jumping ship, the gods may be trying to tell you something in an indirect sort of way. Feelings were inflamed all the more by the fact that his desertion left us without a soothsayer – other, that is, than the tiresome Cassandra, whom nobody believed, since she claimed to have rejected the advances of Apollo himself. Besides, if you’re forever foretelling catastrophe, people disbelieve you because they can’t afford to do otherwise. So Cassandra was generally disbelieved and Calchas was generally reviled, which was easier to do than to reconsider the casus belli, namely the presence of the man-loving Helen within our besieged walls. Public opinion being what it is – that is, irrational, hysterical and essentially vindictive – there were outcries that he should be cast from the battlements of Troy along with all his family. Since Calchas himself was not within casting distance, thoughts turned to the daughter he had left to her fate, my aforementioned niece, Criseyde.

I had, as I say, rather lost touch with Calchas, but being only about five years older than my niece – she was twenty-three at this stage, and I was twenty-eight – I had of late been to see her occasionally at her house, where she kept herself aloof from the social gatherings that the upper classes of Troy were still arranging, in spite of the siege – indeed, perhaps all the more assiduously for the siege. She was a nice enough young woman, easy on the eye, demure, reserved, as befitted her status as a young widow – her husband, whom she had married at a very young age, having been killed in a skirmish with the Greeks early on in the siege. She was alone, defenceless and, as I say, pretty: it follows that she was the natural target of people who wanted Calchas punished and couldn’t get at him in any more direct way. They accordingly let her know that they thought she was a bit of no-good and should be dealt with accordingly. She naturally felt this, not only as a threat against her life, but as a blot upon her honour, as if she were in some way implicated in her father’s treason. She was a woman not only of a certain shrinking timidity but also of tender conscience and sensitive pride. She would have made an admirable wife to a warrior; as a widow, she lacked toughness under pressure.

I had, of course, heard the mutterings and mumblings against Criseyde in public places, but had not really given them an ear: I had recently had a setback in my own affairs of the heart, and I was not inclined to hang about with the gossips of the city. But the essentials of her story were common knowledge, and the rest of it I have had to piece together in retrospect from my many conversations with the lovers – they were nothing if not talkative – and here and there I have had to supplement my information with my imagination.

What Criseyde did, with the instinct of conscious vulnerability, was to address herself to the most powerful man she could think of: Hector, the eldest son of Priam, and commander of the Trojan forces. Whether she knew it or not, Hector was also a bit of a softy, especially towards helpless young women. There had been, some time ago, a near-scandal concerning the nurse of his son, Astyanax; but his wife, the highly respected Andromache, had stood by him, and it was generally assumed that the young woman had either mistaken Hector’s solicitude for an advance, or hoped to blackmail him into giving advancement to her lover, a young soldier. The nurse was replaced with another young woman, and the matter was soon forgotten. The point is, though, that Hector had a susceptible heart, and Criseyde chose well in going to him: apart from his amen able nature, he was one of the few men other than his father who had the authority to enforce his patronage of her without scandal or resistance.

Criseyde, for all that she was sincerely distraught, must have had a flair for drama, for she flung herself upon her knees in front of Hector as he was approaching the palace at the end of a day’s fighting. She looked, I am told, very fetching in her blue-black widow’s veil. It would have taken a more insensible man than the tender-hearted Hector to resist her: despite the veil, he could not have failed to notice that she was very pretty, and she wisely made no attempt to justify her father’s action, basing such claim as she had purely on her own innocence and ignorance.

‘Let your father’s treason be your father’s portion and his curse,’ the large-hearted Hector declared, ‘and let it not be reckoned to your account. Stay here with us in Troy, by all means, and be assured of my protection. I shall command all men, upon pain of death, to show you respect as if your father had never been disgraced. And all women,’ he added as a prudent afterthought, knowing his city as he did.

Criseyde thanked Hector prettily; but, like many men of action, he did not like public avowals of indebtedness, believing it an act of vanity to be seen to accept them passively and knowing the gods not to take kindly to such presumption. So he deprecated her gratitude and retreated to his quarters, where, in truth, with his wife and son, he felt most comfortable. Grateful-hearted Criseyde, for her part, made her way to her own house, a not inconsiderable palace left her by her husband, where she dwelt quietly with a respectable retinue of female servants and companions.

The fortunes of war, meanwhile, took their usual changeable course; if there was a divine design behind the vicissitudes, it was not evident in the daily details of battle. These have been described in full and at times tedious detail elsewhere, and I let the matter pass as a distraction from my concern with the history of the young lovers. I am a chronicler of love’s stormy passage, not a military historian.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts I am Pandarus Jonathan Ball Publishers Michiel Heyns